Why Experiential Learning?

The UWM 2030 Report recommends revisions to the undergraduate experience to “implement an Experiential Learning requirement for all programs” (5). According to the report, “UWM currently offers many forms of [experiential learning] that are well designed and supported, and which can be organized into eight buckets” (120): Professional, Undergraduate Research, Study Abroad, Leadership Experiences, Internships, Creative/Entrepreneurial, Service Learning, and Technical/Vocational.

While these forms of experiential learning are highly beneficial to students, they are mainly focused on specific course types (i.e., service learning) or experiences independent of courses (i.e., leadership experiences) rather than activities that take place within the context of individual courses. By exploring experiential learning within courses—particularly those offered in the online modality—instructors can both enhance course quality and provide greater opportunities for deep learning among students who may not participate in traditional experiential learning outside of courses.

To expand upon this university recommendation, CETL’s Experiential Learning in Online Courses initiative has the following goals:

- Identify what experiential learning can look like in online courses and programs

- Understand how experiential learning can impact online students

- Provide examples to other online instructors at UWM

What is Experiential Learning?

In his book, Experiential Learning, David A. Kolb describes learning as “the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience” (49). Experiential learning focuses less on meeting pre-determined learning objectives and more on making use of students’ individual experiences for knowledge production.

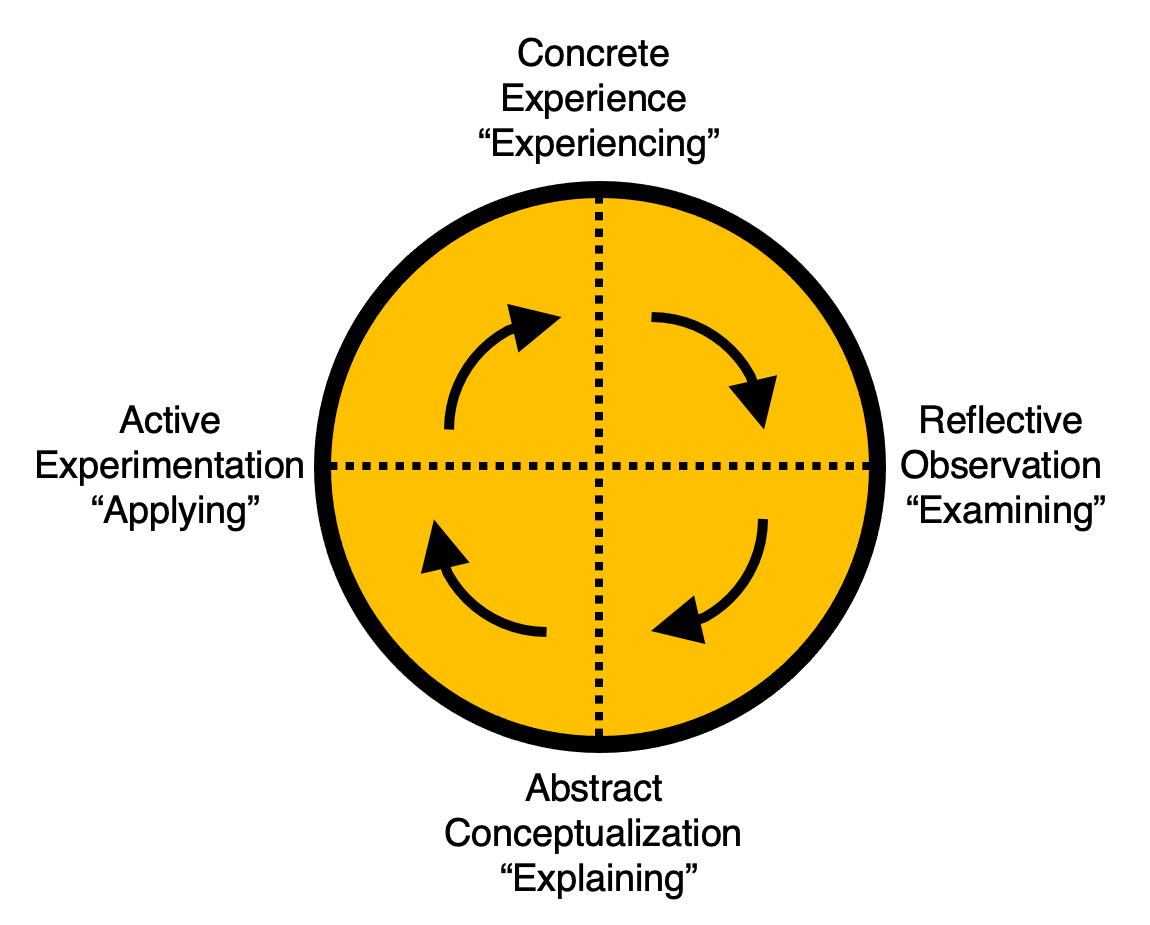

Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle (see below) is based upon four dimensions of the learning process: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation.

Marilla D. Svinicki and Nancy M. Dixon describe the Kolb Experiential Learning Cycle as follows: “The cycle begins with the learner’s personal involvement in a specific experience. The learner reflects on this experience from many viewpoints, seeking to find its meaning. Out of this reflection the learner draws logical conclusions (abstract conceptualization) and may add to his or her own conclusions the theoretical constructs of others. These conclusions and constructs guide decisions and actions (active experimentation) that lead to new concrete experiences” (141).

Marilla D. Svinicki and Nancy M. Dixon describe the Kolb Experiential Learning Cycle as follows: “The cycle begins with the learner’s personal involvement in a specific experience. The learner reflects on this experience from many viewpoints, seeking to find its meaning. Out of this reflection the learner draws logical conclusions (abstract conceptualization) and may add to his or her own conclusions the theoretical constructs of others. These conclusions and constructs guide decisions and actions (active experimentation) that lead to new concrete experiences” (141).

The following example from an online Games in Society course pairs each dimension with an accompanying activity:

- Concrete experience: Play a virtual tabletop game you have never played before

- Reflective observation: Describe in a reading response what makes the game a game, what makes the game fun, and how this game relates to other games you’ve played

- Abstract conceptualization: Read articles on game design and analyze the selected game through this lens

- Active experimentation: Develop a virtual tabletop game of your own design

Other examples of experiential learning, which can be applied to online courses, include:

- Problem-based learning

- Case-based learning

- Project-based learning

- Inquiry-based learning

References

- Kolb, D. A. (2015). Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development / David A. Kolb. (Second edition.). Pearson Education, Inc.

- Svinicki, M. D., & Dixon, N. M. (1987). The Kolb Model Modified for Classroom Activities. College Teaching, 35(4), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.1987.9925469

Please contact the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning with any questions.