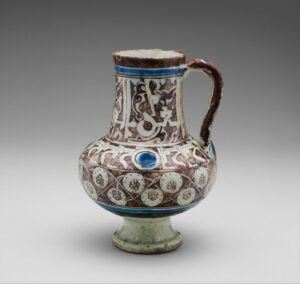

Figure 1. Pitcher. Iran (Garrus), 13th century CE. Ceramic with Glaze. Credit Line: Gift of Mr. And Mrs. Carl Moebius. UWM Art Collection, 1985.086.

David Symanzik-Stock

Art Expose

Spring 2023

Introduction

The provenance of objects in museum collections is always a complicated, and often undecipherable, mystery. It is, however, important to achieve as accurate an understanding of the origins of objects held in these collections as possible to better understand the scope and content of these collections.[i] A 13th century CE Persian pitcher held in the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee Art Collection (UWM Art Collection; 1985.086), (Fig. 1), provides an interesting case study as to both the necessity of continued provenance studies on objects in museum collections, but also as to the unfortunate difficulty with such studies. The buff clay ceramic pitcher is coated in a translucent turquoise glaze and is highly decorated with black pigment. Its two main registers incorporate important iconographic elements, typical of the region and period, and the striking turquoise colour, along with the particular dipping applization technique, of the glaze offer some interesting opportunities for better understanding the provenance of the object. As a graduate student research intern, I undertook an exploration of this vessel, aiming to better understand its importance in the UWM Art Collection. Due to the lack of information currently available on the object specifically, this study necessitated the review of comparative objects – resulting in the conclusion that the small amount of provenance information available for this vessel might actually need continued research and scrutiny in order to more accurately place this piece in its contextual time and place. Through a comparative visual analysis, the study of this vessel suggests that it is, in fact, not from the Garrus region (or eponymous ware-type) as suggested by initial provenance research but is more likely following ceramic trends from workshops in the Raqqa region, located in Northeastern Syria.[ii] This conclusion not only helps us to better understand the object itself, but also illuminates the true breadth and diversity of objects held in the UWM Art Collection.

The 13th century in the region which is now comprised of northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northeastern Syria saw social interaction between significant empires. In Iran and Iraq the Ilkhanid Dynasty (a smaller offshoot of the larger Mongolian Empire, which stretched from the western Pacific coast to eastern Turkey and Mesopotamia) was formed after Mongolian conquests in the early 13th century. The dynasty’s seat of political power in the region moved during the conquests to northwestern Iran and the ruling Ilkhanid elite soon after adopted Islam as their official region. Although initially very disruptive to ceramic production, the absorption of this region into the larger Mongolian Empire resulted in an environment of huge cultural exchange. Following the introduction of particularly active pro-Islamic cultural policies towards the end of the 13th century, ceramics flourished and began incorporating [iii] While northeastern Syria also fell under Ilkhanid rule for the majority of this period, this region bordered Ayyubid, Crusader, and Mamluk controlled regions and by the end of the 13th century was under Mamluk control.[iv] Thus, collectively, these regions were exposed to an influx of ceramics and production techniques from further east – through the Mongolian Empire – but also, to some extent, from the west through connections to Mesopotamian and Eastern Mediterranean trade centers. We see these influences making their way into the design and production of ceramics made locally within these regions – some of which are evident in the UWM Art Collection’s 13th century pitcher.

Visual Analysis of 1985.086

The UWM Art Collection’s pitcher, dating to the 13th century, exhibits some typical iconographic, morphological, and material elements from this region and period. The pitcher, commonly termed a medium-neck jug, has a circular rim with its neck extending almost completely vertically from the rim to the shoulder of the vessel, which it meets about halfway down the total height of the jug. A handle loops from the top of the neck to the shoulder of the vessel. The body of the jug extends outward from the shoulder and around, finishing at the base – altogether forming a gourd-like appearance with the neck of the vessel. The jug is completed by a circular foot at the base, approximately of similar diameter to that of the opening of the vessel. This particular shape is reminiscent of other contemporary jugs, such as this 13th century Syrian ewer from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fig. 2):

Figure 2. Ewer Inscribed with “al-‘izz” (“Glory”) in Floriated Kufic on its Neck. Syria (Raqqa), first half of the 13th century CE. Stonepaste with Glaze. Credit Line: HO Havemeyer Collection, Gift of Horace Havemeyer, 1948. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 48.113.18.[v]

Iconography on the vessel also matches contemporaneous Persian examples, with a black band around the rim of the vessel, black geometric lines and forms in three separate registers (one on the neck, one on the shoulder, and the third on the body) circumscribing the vessel. Black horizontal bands are also painted at somewhat regular (but haphazard) intervals on the handle. Alongside the geometric elements, the highlight of the black painted iconography appears to be what’s known as kufic script. This technique, developed under Seljuk rule in the 12th century CE, involves morphing calligraphic text (specifically Arabic) along the surface of an object. The script often reads as just one or two words of a positive nature, such as “blessing” or “luck”. While a translation of the kufic script on this particular pitcher has yet to be done, based on similar script on a vessel at the Walters Art Museum (Fig. 3), it’s possible that the UWM Art Collection jug’s text contains a single portion (separated here by commas) of the following phrase: “Lasting glory, increasing prosperity, mounting good fortune, total happiness”.

Figure 3. Arabesques. Syria, ca. mid 12th – mid 13th century Ceramic. Credit Line: Acquired by Henry Walters. The Walters Museum of Art (Baltimore, MD), 48.1117.[vi]

Most striking, however, is the turquoise glaze covering the majority (but not all) of the vessel. The glaze itself is likely a combination of various local materials, notably including copper (possibly with a mixture of tin and lead) as the coloring agent which provides the impressive blue-green colour.[vii] It is possible that this particular glaze type was developed to provide a rival to imported Chinese porcelain ceramics. Furthermore, based on the untreated foot of the jug, it appears that the vessel was dipped into the glaze. This method was pretty common and there are many examples of medieval ceramics from this period and region which appear to have been glazed this way. As the glaze did not drip fully over the vessel, however, we can see, near the exposed foot, that the black painted iconography of the vessel was quite likely applied first, prior to the application of the turquoise glaze.

Discussion

This jug (Fig. 1) came into the UWM Art Collection in 1985 as part of a larger collection of ceramics, glass, metals, and paintings, in the form of a long-term loan from Carl and Janet Moebius. In the early 1990s the collection of objects, including 1985.086, was permanently donated to the collection and underwent the process of accession, or the recording and registration of the objects (from a single source) for the permanent collection and, in this case, the transfer of title of ownership from Carl and Janet Moebius to the UWM Art Collection.[viii] As part of this transition, an appraisal of the objects was conducted which assessed various aspects of the objects in the accession, such as their material, type, and iconography, alongside similar objects from commercial collections as well as research from academic (such as books) and industry (such as sale catalogues) sources. While many objects in the collection not only received detailed descriptions in the appraisal documents but also sources of comparative objects and research, object 1985.086 had no additional sources or comparative objects. Based on the appraisal documents (which provided the only specific mention of this particular vessel), object 1985.086 was determined to be Garrus-ware, although no sources or comparative objects were cited, and so it was necessary to further investigate how such a conclusion might have been achieved.

This particular type of ware, produced around the 13th century CE, was named for the region it predominantly comes from, Garrus, in northwestern Iran. The key features of this ware are a thick, deep green glaze, with incised linear, geometric, floral, and faunal decoration.[ix] In the process of this particular study of 1985.086, in an attempt to understand why the connection between Garrus-ware and this specific vessel was made, comparative objects from other collections were consulted. In particular, a lid from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fig. 4) and a fritware jug from the David Collection in Copenhagen (Fig. 5) provide particularly clear examples of this type of ware.

Figure 4. Lid. Iran (Garrus), c. 12th – 13th century CE. Earthernware with Slip. Credit Line: Purchase, Edward C. Moore Jr. Gift, 1927. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 27.13.4

Figure 5. Jug. Iran, c. late 12th century CE. Fritware with Decoration Cut Through Slip. The David Collection, Copenhagen, 3/1975.

In both cases, the most distinctive element which denotes the Garrus-ware type is the incised decoration. In the case of Garrus-ware, the undercoat is applied to the vessel’s surface and set aside until the undercoat has somewhat hardened. In this thicker surface, the decoration is incised, and additional pigments are applied. The vessel is then finished with an additional clear (or occasionally a highly transparent turquoise) glaze. Notably, however, the indentation left by the incised iconography remains present across the surface of the vessel. Furthermore, as is present in Figure 4, the glazes for Garrus-ware are almost always of a darker green finish (likely due to additional copper mixed into the glaze).

In the case of the jug in the UWM Art Collection (1985.086), we do not have any suggestion of incised decoration, unlike the Garrus-ware objects from other collections. Instead, the decoration, as can be seen through some small chips of glaze as well as beneath the glaze-line near the foot of the vessel, appears to have been applied directly to the untreated surface of the vessel. Additionally, we are lacking the increased green hue of glazes typically associated with Garrus-ware objects. While further research is necessary to better identify whether this jug is an anomalous example of Garrus-ware, as the glaze colour and production of decoration are questionably different on the vessels I found in other collections of Garrus-ware (exemplified by those in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5) than on the one in the UWM Art Collection, I thus broadened my research to consider typical approaches in other contemporaneous ware-types, under the assumption that the jug in the UWM Art Collection is more likely representative of typical production and artistic methods than of unique methods. In following this approach, it appears that the jug in the UWM Art Collection is more closely aligned with typical Raqqa-ware methods of production and decoration.

Raqqa-ware is noted for a couple of predominant traits which more closely match those of the vessel in the UWM Art Collection. In particular, the dripped turquoise glazing along with the pre-glaze addition of iconography, matches what we see in the jug at UWM. An excellent example of this technique can be seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Jar. Syria (Raqqa), ca. late 12th century – early 13th century CE. Stonepast, painted under transparent turquoise glaze. Credit Line: H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Horace Havemeyer, 1956. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 56.158.18.[x]

In addition to the jug shape as a contemporaneous form in Raqqa ceramics (Fig. 2), the clear turquoise glaze on the jar in Figure 6 appears somewhat similar to the UWM Art Collection 1985.086. In the UWM jug not only do we see evidence of iconography painted onto the untreated ceramic surface, as can also be seen in Figure 6, but we also see the use of multiple black bands around the rim and neck of the vessel. There is also iconographic similarity between the geometric register on the shoulder of the jar in Figure 6 as well as on the shoulder of the UWM Art Collection jug. Kufic script and an abstract geometric or florally-inspired background is also seen in the registers on the bodies of both vessels. While these iconographic elements appear to be similar across several 13th century ware-types, examples from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (as shown in Figure 6; see also endnotes) appear to provide very close similarities to 1985.086.

Comparing the two types of ware, Garrus and Raqqa, it seems likely that the object in the UWM Art Collection is more closely related to Raqqa-ware than Garrus. The similarity in production techniques suggests that, even if this vessel was produced in the Garrus region, it was heavily inspired by ceramics produced in Raqqa. What, then, does this mean for the vessel? Unfortunately, due to the lack of archival information and without further study, there is little further that can be concluded regarding the jug. Given volume of decoration on the exterior of the vessel (the interior is blank), along with the potential meaning of the kufic script, and the lack of a spout (for efficient pouring), it’s likely that this vessel served a symbolic or functional purpose that did not involve it being used as a container or pourer. While it may be intended to mimic such forms, it is possible that this vessel was more for presentation than use. This does, to some extent, muddy further provenance studies of this object as Raqqa, located in northeastern Syria – within the Ilkhanate borders – would have been within reasonable distance of the Garrus region. This object may have been produced by a workshop in or around Raqqa and subsequently exported to Garrus and presented as part of a broader social interaction between individuals from both regions. Alternatively, with so little information to go on (a problem museums are almost always faced with), it’s also possible that this vessel could have been produced in imitation of Raqqa ware, opening up a number of other possibilities as to its origin.

These functional assumptions aside, the case of this jug from the UWM Art Collection highlights how continued study of objects held in museum collections, however brief, can turn up new questions and new possibilities. Due to the lack of information, such exploration heavily relied on comparative objects, intrinsically connecting the object at UWM to other collections across the US. Furthermore, while this study highlights the shortcomings of just how little can be concluded from such a study, it also highlights that the process of asking and challenging assumed designations can encourage a more wholistic, complex, and interesting conversation not only about the objects themselves, but also of their place within the UWM Art Collection.

Bibliography

Bernsted, Anne-Marie Keblow. Early Islamic Pottery: Materials and Techniques. London: Archetype, 2003.

Boarati, Molly. “Why Does Provenance Matter?” September 17, 2017. Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University. Accessed, May 5, 2023. https://nasher.duke.edu/stories/why-does-provenance-matter/.

Carnell, Clarisse and Rebecca Buck. ”3B: Acquisitions and Accessioning.” In MRM5: Museum Registration Methods, edited by Rebecca A. Buck and Jean Allman Gilmore, 44-57. Washington DC: American Association of Museums (AAM) Press, 2010.

Consiglio, Brian. “Provenance: how an object’s origin can facilitate authentic, inclusive storytelling: SISLT’s Buchanan researching better ways to archive history.” May 20, 2021. College of Education and Human Development: University of Missouri. Accessed, May 5, 2023. https://education.missouri.edu/2021/05/provenance-how-an-objects-origin-can-facilitate-authentic-inclusive-storytelling/.

Douglas, Jennifer. “Toward More Honest Description.” The American Archivist 79, no. 1 (2016): 26–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26356699.

Fayet, Roger. “‘CLEAN’ COLLECTIONS: On the Idea of Contamination in the Provenance Discussion.” CrossCurrents 69, no. 3 (2019): 277–90. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26842578.

Jenkins-Madina, Marilyn. Raqqa Revisited: Ceramics of Ayyubid Syria. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2006.

Yalman, Suzan, ed. “The Art of the Ilkhanid Period (1256–1353).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2001. Accessed, May 5, 2023. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ilkh/hd_ilkh.htm.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. “The Eastern Mediterranean, 1000–1400 A.D.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2001. Accessed, May 5, 2023. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/?period=07®ion=wae.

[i] While there are numerous studies on the value, and how, of provenance research – Molly Boanarti, Associate Curator of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University provides an exemplary (if brief) discussion of the importance behind understanding provenance (Boarati 2017); see also Consiglio 2021; Fayett 2019; and Douglas 2016

[ii] Garrus (and Garrus-ware) is alternatively spelled Garros (Garros-ware)

[iii] Yalman, Suzan, “The Art of the Ilkhanid Period (1256–1353),” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2001, accessed May 5, 2023. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ilkh/hd_ilkh.htm

[iv] “The Eastern Mediterranean, 1000–1400 A.D,” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2001, accessed May 5, 2023. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/?period=07®ion=wae

[v] For more information and comparative objects, see Marilyn Jenkins-Madina, Raqqa Revisited (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2006),136-138, 140 (MMA21-23, 25).

[vi] For more information and comparative objects, see Jenkins-Madina Raqqa Revisited, 85 (W90).

[vii] Anne-Marie Keblow Bernsted. Early Islamic Pottery (London: Archetype, 2003), 4-7; 44-50.

[viii] Description of accession based on those provided by Clarisse Carnell and Rebecca Buck, ”3B: Acquisitions and Accessioning,” in MRM5: Museum Registration Methods, eds. Rebecca A. Buck and Jean Allman Gilmore (Washington DC: American Association of Museums (AAM) Press, 2010), 51-52.

[ix] Bernsted, Early Islamic Pottery: Materials & Techniques, 19-23 ; see also Met Lid

[x] For more information and comparative objects, see Jenkins-Madina Raqqa Revisited, 150-157 (MMA35 – MMA42).