Roman Amphoriskos in the UWM Art Collection

Katie Batagianis

In the ancient Roman world, glass was ubiquitous. It was used to create jewelry and other ornaments, to form the designs in floor mosaics, and to insulate the famed Roman baths.[1] It was also an extremely popular material for vessels of every conceivable shape and function: oil lamps, cosmetic and jewelry boxes, storage and transport containers, perfume bottles, ointment pots, and wine jugs and cups, among many others. Glass vessels were, in fact, such an integral part of daily life in the Roman empire that an estimated 100 million of them were produced every year.[2] Amazingly, considering the inherent fragility of the material, an impressive amount of these glasswares have survived to the present, and several major museums boast extensive collections (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Greek and Roman glassworks in the J. Paul Getty Museum

With such a profusion of surviving examples, it might be easy to dismiss this amphoriskos in the UWM Art Collection. After all, there is nothing particularly spectacular about it. Measuring just 2.875 inches in height and 3.25 inches in width, it is quite small. Its decoration is minimal, and, though the vessel is intact, it exhibits significant areas of damage, as can be seen in the many flaky patches that mar the vessel’s surface. Even its most visually arresting components – the swirls of brilliant rainbow colors and the sparkling quality that makes it appear as though the vessel has been sprinkled with glitter – are not uncommon features in surviving glassworks from the ancient world. And yet, this amphoriskos is nevertheless a compelling object, both as a representative of a significant part of ancient Roman material culture and as an individual artifact with its own story to tell.

*****

The first part of this vessel’s story concerns the manner of its creation. This amphoriskos – or “small amphora,” called thus because of its resemblance in miniature to the large, two-handled vessels used to store and transport olive oil and wine[3] – is an example of blown glass. This technique, developed on the Levantine coast in the first century BCE[4] and then brought to Rome by Syrian and Judean slaves in the first century CE,[5] completely transformed the ancient glass industry. Before glassblowing, the manufacture of glass was a slow and complicated process, and, consequently, glassware was a luxury item available only to the wealthy.[6] With the development of glassblowing, however, production became quicker and easier, costs went down, and a much broader swath of the population could afford to purchase glassworks.[7]

The process of glassblowing consists of placing a glob of molten glass on one end of a long metal tube known as a blowpipe and then blowing through the pipe to inflate the glass.[8] In the method of glassblowing known as mold-blowing, the molten glass is inflated inside a prepared mold, and the glass then takes on the form of that mold, as well as any decoration carved inside the mold.[9] In the alternative method of glassblowing, known as free-blowing, the shape, size, and decoration of the vessel are completely dependent upon the glassworker. After inflating the molten glass, the worker can manipulate the form in a number of ways: by rolling the glass on a smooth surface, by swinging the glass around on the blowpipe, or by using tools.[10]

Figure 2 – Mold-blown vessel with seam (highlighted) and relief decoration, Roman, c. 50-80 CE, Metropolitan Museum of Art

The UWM amphoriskos is an example of a free-blown vessel, as indicated by a few key features. For one, a mold-blown vessel will show the seams from the mold used to create it, and it will often have decoration rendered in relief (Figure 2).[11] The UWM amphoriskos has neither of these characteristics. It does, however, have what is known as a pontil scar, the telltale sign of a free-blown vessel.[12] Once a free-blown vessel has been formed, it must be broken off from the blowpipe and the mouth and neck reheated and reworked. To hold the vessel while this is being done, a second rod, known as a pontil, is attached to the bottom. When the vessel has taken its final shape, the pontil is removed, and a circular scar is left at the point of attachment.[13] As seen in Figure 3, the bottom of the UWM amphoriskos has just such a scar.

Figure 3 – Pontil scar on the bottom of the UWM amphoriskos

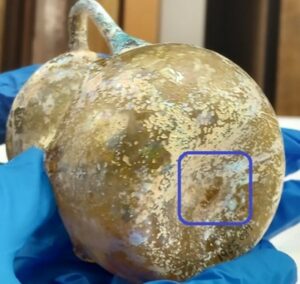

Though the glassblowing technique made glass vessels cheaper, it did not inherently make them all equal. Some glassworks continued to be considered luxury wares, particularly works displaying the extremely intricate carving of cameo decoration (Figure 4). Other luxury wares included those with mosaic decoration and those that incorporated gold leaf between layers of glass.[14] It seems likely that the UWM amphoriskos was on the lowest end of the luxury spectrum. There is very little decoration, and certainly nothing elaborate. It consists solely of a single band of protrusions that runs around the middle of the vessel’s globular body (Figure 5). These protrusions, known as fins, are created by pinching the glass at various intervals while the glass is still hot.[15]

Figure 4 – Cameo glass skyphos, Roman, 25 BCE-25 CE, J. Paul Getty Museum

Figure 5 – Detail of body showing protruding fins

Another indication that this amphoriskos was likely on the cheaper side relates to the handles. Added separately following the completion of the vessel itself, the handles appear to have been attached quite carelessly. The points of attachment on the body and mouth are sloppy and imprecise, and a view of the top of the amphoriskos reveals that the handles are not equidistant (Figure 6). This inattention to detail afflicts many Roman glass vessels with handles, as illustrated in the example in Figure 7. As one scholar lamented, “In almost every instance handles are heavy and awkward, joined to the vase in a crude fashion that bespeaks no architectonic sense. By the addition of handles many otherwise beautiful shapes are marred.”[16] However, as other vessels attest, at least some glassworkers possessed the necessary skills to deftly attach handles. This ewer at the Corning Museum of Glass (Figure 8), for example, boasts a handle that is beautifully crafted and connected. The subpar handiwork of handles like those of the UWM amphoriskos suggests a concern for speed of production rather than quality of appearance, further reinforcing the notion that it was a cheap purchase.

Figure 6 – View of the UWM amphoriskos from above

Color constitutes another part of the story of the UWM amphoriskos. Ancient Roman glassworkers were able to produce wares in an impressive array of hues. The creation of color in glass can be achieved in one of two ways during the glassmaking process: by adding metallic oxides to the glass mixture or by controlling the amount of oxygen in the furnace.[17] While the damage to the UWM amphoriskos obfuscates much of the vessel’s surface area, enough remains visible to discern that its original color was a sort of yellow-brown, perhaps something in the vein of a honey or amber tone. Figure 9 provides an example of an undamaged amphoriskos whose color may be similar to the UWM vessel’s initial hue. Such a color would have been created by either adding a mineral like lead or depriving the furnace of oxygen during the production process.[18]

Figure 7 – Amphoriskos, Roman, 1st century CE, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Why the artisan who made the UWM amphoriskos chose to make it yellow remains a mystery. The dictates of fashion certainly played a role in ancient Roman glass manufacture. We know, for example, that colorless glasswares were in vogue for a period during the first century CE.[19] Perhaps yellow was a popular color choice for amphoriskoi at the time (late third to early fifth century CE) and in the region (eastern Mediterranean) where the UWM vessel was created. It is also possible that the color of the amphoriskos was less about making a decorative decision and more about making use of what was at hand. Unlike ceramics, glass can be melted down and reused after it is broken,[20] so perhaps the amphoriskos artisan simply made a yellow vessel because they had shards of yellow glass available. The mismatched colors of the handles and bodies of some Roman glasswares (Figure 9) at least suggests that workers used whatever scraps were on hand, regardless of color coordination – though, of course, this might also have been a conscious decision to lend the vessel some visual interest.

Figure 8 – Ewer, Roman, 30-70 CE, Corning Museum of Glass

Another possible explanation for the color of the amphoriskos relates to its function. Amphoriskoi were used to hold perfume, and it has been theorized that bottle colors were directly linked to bottle contents.[21] For example, a floral fragrance might have been kept in an amphoriskos of one color, while a different color might have designated a spicy or fruity scent. It is also possible that a bottle’s color indicated the intended purpose of its contents. In the Roman world, perfume was used in a number of capacities: as a remedy for body odor, as a medicinal treatment, as part of the ritual of cleaning and anointing a dead body in preparation for burial, and so on.[22] Perhaps the purpose of the perfume played a part in the choice of bottle color, too.

Figure 9 – Amphoriskos, Roman, 1st century CE, Metropolitan Museum of Art

The story of the UWM amphoriskos would not be complete without a discussion of the stunning bursts of color that now decorate portions of its surface, particularly its mouth and handles (Figure 10) and the bottom half of its body (Figure 11). This quality is known as iridescence, and it is, unfortunately, an indication that the amphoriskos is in extremely poor condition. Iridescence is the result of weathering, a process that affects a number of ancient glass vessels due to their burial in the ground as part of Roman funerary ritual.[23] During the imperial period, Romans practiced both cremation and inhumation, and in cases of inhumation, a number of different types of goods were buried with the dead. These were items that it was believed the dead would need in the afterlife, that would make them comfortable there, including games, eating utensils, weapons, jewelry, and various toiletry items, such as perfume bottles.[24] If glass is exposed to moisture while underground, and if that exposure lasts for an extended period of time, then a chemical reaction occurs.[25] Iridescence is only one of several consequences that could result from this chemical reaction; the disintegration of the outer surface of the glass into a flaky coat that breaks off is another.[26] This, too, can be seen on the UWM amphoriskos. Sadly, there is nothing that can be done to either stop or reverse this process.[27] Nor is cleaning an option, as removal of the flaky coat, which is actually protecting the glass underneath, would cause the glass to disintegrate even further.[28]

*****

When we think of the material culture of ancient Rome, glass is probably not something that immediately comes to mind. But perhaps it should, as glass – particularly glass vessels – was a fundamental part of everyday life in the Roman empire. And while the UWM amphoriskos, and other glasswares like it, is not a wall painting from Pompeii, a portrait sculpture of the emperor Augustus, or another renowned work of the ancient Roman world, it nonetheless deserves to be seen, to be studied, and to be appreciated in its own right.

[1]Rosemarie Trentinella, “Roman Glass,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed February 11, 2023, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/rgls/hd_rgls.htm.

[2] Donald White et al., Guide to the Etruscan and Roman Worlds at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, ed. Lee Horne (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2002), 66.

[3] “Amphoriskos (Container for Oil),” The Art Institute of Chicago, accessed February 16, 2023, https://www.artic.edu/artworks/67448/amphoriskos-container-for-oil.

[4] Stefano Carboni, “Introduction,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 59, no. 1 (Summer 2001): 6.

[5] White et al., Etruscan and Roman Worlds, 66.

[6] Karol B. Wight, Molten Color: Glassmaking in Antiquity (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011), 53.

[7] “Glass of the Romans,” Corning Museum of Glass, accessed April 24, 2023, https://whatson.cmog.org/exhibitions-galleries/glass-romans.

[8] R. A. Grossmann, Ancient Glass: A Guide to the Yale Collection (New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2002), 10.

[9] Grossmann, Ancient Glass, 13.

[10] Grossmann, Ancient Glass, 10.

[11] Stuart J. Fleming, Roman Glass: Reflections on Cultural Change (Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 1999), 37-38.

[12] Fleming, Roman Glass, 34.

[13] Anastassios Antonaras, Fire and Sand: Ancient Glass in the Princeton University Art Museum (Princeton: Princeton University Art Museum, 2012), 24.

[14] Catherine Hess and Timothy Husband, European Glass in the J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 1997), 3.

[15] Antonaras, Fire and Sand, 33.

[16] Eleanor E. Rambo, “Ancient Roman Glass,” The Museum Journal 11, no. 2 (June 1920): 33.

[17] Fleming, Roman Glass, 138, 141.

[18] Fleming, Roman Glass, 138, 144.

[19] Fleming, Roman Glass, 44.

[20] Ian C. Freestone, “The Recycling and Reuse of Roman Glass: Analytical Approaches,” Journal of Glass Studies 57 (2015): 29.

[21] “Largest Ever Exhibition of Mold-Blown Glass from Ancient Rome Organized by The Corning Museum of Glass,” Corning Museum of Glass, accessed May 6, 2023, https://press.cmog.org/2014/largest-ever-exhibition-mold-blown-glass-ancient-rome-organized.

[22] Erin Branham, “The Scent of Love: Ancient Perfumes,” The J. Paul Getty Museum, accessed May 10, 2023, https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/the-scent-of-love-ancient-perfumes/.

[23] Grossman, Ancient Glass, 11.

[24] J. M. C. Toynbee, Death and Burial in the Roman World (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1971), 52-53.

[25] Astrid van Giffen, “Glass Corrosion: Weathering,” Corning Museum of Glass, accessed February 11, 2023, https://blog.cmog.org/2011/09/14/glass-corrosion-weathering/.

[26] Fleming, Roman Glass, 61.

[27] Fleming, Roman Glass, 148.

[28] Van Giffen, “Glass Corrosion.”