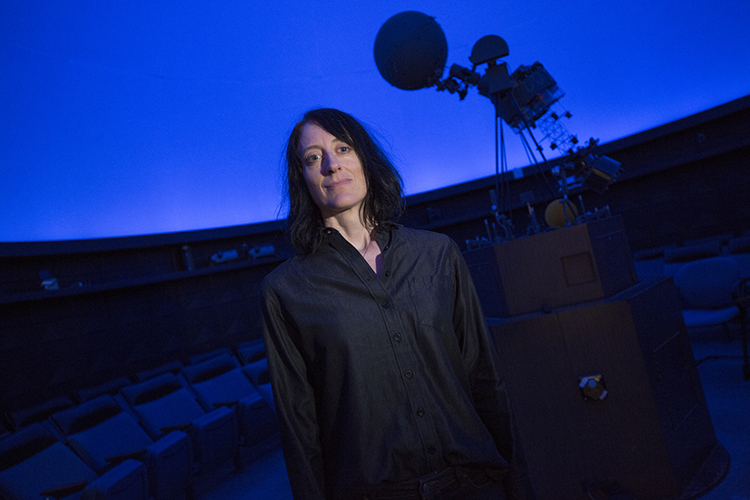

A team of astronomers led by Dawn Erb at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee has found a new way to unlock the mysteries of how the first galaxies formed and evolved.

In the study, published today in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, the researchers used new capabilities of the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii to examine a particular ultraviolet wavelength of light that illuminates a gaseous halo surrounding Q2343-BX418, a small, young galaxy about 10 billion light years from Earth that is an analog for younger galaxies that are too distant to study in detail.

The gas halo around BX418 gives off a special type of light called Lyman alpha emission. This emission acts as a tracer for the gas because its photons are absorbed and re-emitted by hydrogen in the halo, enabling astronomers to study the motions and spatial extent of the gas.

“There are a lot of different theories about what produces this Lyman alpha emission in the halos of galaxies, but at least some of it is probably due to light that is originally produced by star formation in the galaxy being absorbed and re-emitted by gas in the halo,” said Erb, an associate professor of physics at UWM.

The scientists believe the complex interactions within the halo could reveal how galaxies form stars and grow. It’s where some of the galaxy’s gas escapes, driven by star formation in the galaxy, and some of the gas from the surrounding environment, called the “intergalactic medium,” enters the system.

“The outflows of gas limit a galaxy’s ability to form stars by removing gas, while the inflow of new gas provides fuel for new star formation,” said Erb. “So, understanding what is happening in this halo is key to understanding how galaxies grow and evolve.”

With the aid of the Keck Cosmic Web Imager, a spectrograph recently installed on the Keck II telescope, Erb and her colleagues followed the Lyman alpha emission in BX418’s halo.

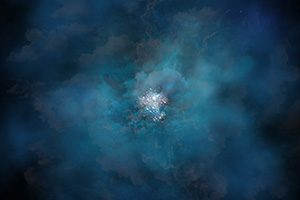

The researchers tracked the emission for the first time over a halo region 10 times larger than the galaxy itself, a study enabled by the new design of the spectrograph that separates the light of each pixel of an image by wavelength into a spectrum. They analyzed the emission over an 80,000 by 100,000 light year expanse, with the Keck imager providing the spectral profile of every 8,000 by 8,000 light-year “pixel” of that region.

From the data, the team created a visual representation of both the spatial extent and the velocity patterns of the gas surrounding the galaxy. Their data suggests that the galaxy is surrounded by a roughly spherical outflow of gas and that there are significant variations in the density and velocity range of this gas.

This analysis is the first of its kind, said Erb, so studies of other galaxies need to be conducted to see if the results are typical. The hope is that further analysis of the data they collected and computer modeling of the processes will yield additional insights into the characteristics of the first galaxies in the universe.

“As we work to complete more detailed modeling, we will be able to test how the properties of Lyman alpha emission in the gas halo are related to the properties of the galaxies themselves, which will then tell us something about how the star formation in the galaxy influences the gas in the halo,” Erb said.