Astronomy is one of the most popular sciences, in part, because looking at the night sky is universal, something we all share, Jean Creighton says. But people may also feel a connection for another reason.

“All the elements that are cooked in the core of massive stars and spewed out when those stars explode – including oxygen, carbon and nitrogen – are critical elements for our bodies,” said Creighton, director of UWM’s Manfred Olson Planetarium. “We literally came from stars. These shared connections are certainly a cause for celebration.”

And celebrating is what’s in store three times this month:

- Mae Jemison, the first African American woman in space, will give the Distinguished Lecture on Oct. 10 at 7 p.m. in the Wisconsin Room at the UWM Student Union. Tickets are required. UWM students are admitted free.

- A free viewing party of the partial solar eclipse happens on Oct. 14 between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m., just after the Panther Prowl, in the Cunningham Hall parking lot at the corner of Cramer Street and Hartford Avenue. Because looking at the eclipse can cause eye damage, free NASA-approved glasses will be available as well as free planetarium shows every 30 minutes starting at 12:30 p.m.

- This year marks the 100th anniversary of the first planetarium projector, and UWM will join in with a local event on Oct. 21 from 6-8 p.m. at the UWM planetarium, 1900 E. Kenwood Blvd. Enjoy cake, planetarium stargazing shows and rooftop telescope viewing.

The partial eclipse: a moon shadow

Sometimes, when the moon orbits Earth, the moon comes between the sun and Earth, casting a shadow on the Earth and partially covering the sun. This shadow affects a very small portion of the Earth – so, although a solar eclipse can happen somewhere on Earth every year, it is a rare event for a given location. The next one visible in the Midwest occurs in April 2024, but there won’t be another one until 2044.

This extraordinary phenomenon provides views of something mysterious that we can’t see unless the bright light of the sun is blocked, Creighton said. With specialized equipment, observers can see the sun’s outer atmosphere, known as the corona.

Scientists want to know more about the corona, Creighton said. “The sun, at its surface, is about 6,000 degrees and you would expect that the farther you get from the sun – the nuclear fusion furnace – the cooler it would be,” she said. “Yet the corona can get up to 2 million degrees and we don’t yet understand that. What’s giving that outer layer that kind of energy?”

Such a public “gee-whiz” moment fueled the largest event hosted by the UWM planetarium in 2017 during a near-total solar eclipse that attracted an estimated 2,700 people. At this event, the planetarium staff is prepared with 10,000 NASA glasses.

Centennial of planetariums

For urban dwellers, city lights often interfere with a clear view of the night sky. So how can people view thousands of stars without a telescope and from a comfy reclining chair in a darkened room?

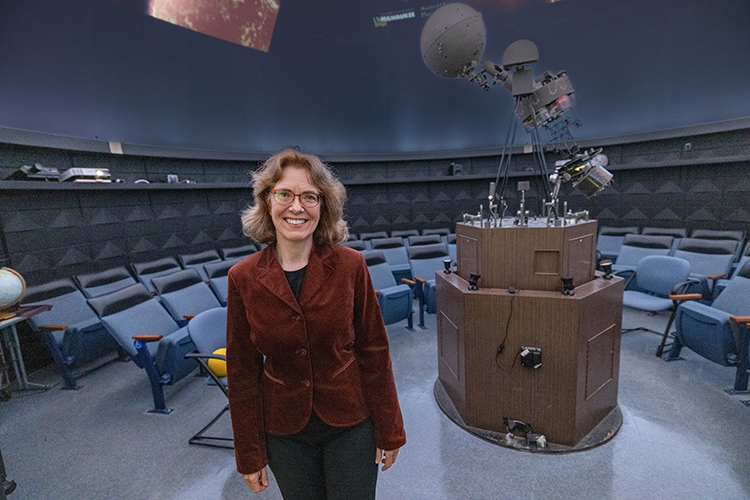

The answer, of course, is a planetarium, where a projector casts images of the planets, moon and stars onto a domed ceiling, creating an accurate representation of the nighttime sky.

The first modern planetarium projector was built 1923 in Munich, Germany. By 1930, the first planetarium in the U.S. had opened – the Adler Planetarium in Chicago.

Creighton estimates that over the last century a billion people have seen the “artificial heavens,” through this resource, spreading both knowledge and wonder about our universe. At the Manfred Olson Planetarium at UWM, the visitor count is estimated at 700,000 in the facility’s 57-year history.

Like a time machine, planetarium projectors show what the sky looks like at different times and from different places with mechanisms for controlling latitude, daily and annual celestial motion.

Support for building UWM’s planetarium in 1965 came from a wave of federal funding during the “space race” of the 1950s and 1960s, after the Soviets launched the satellite Sputnik.

Looking ahead

Today, the aim is to reach new and diverse audiences, Creighton said. “It’s important that a planetarium serves the whole community, not just some sliver of it. So, it’s about knitting astronomy with cultural aspects so that you hook audiences in different ways,” she said.

Some examples of the planetarium’s hybrid cultural programming have included a show for Black History Month, “Under African Skies,” during which audiences could appreciate that the African continent is so large that different stars are visible in Morocco than in Mozambique. The program “Asian Celebrations” explained how the lunar calendar is used to determine major festivals.

And, even though its projector isn’t a digital, computer-driven model, Creighton said that sometimes, old-school delivers a better experience. UWM’s optomechanical projector is dominated by the starball, which has an array of lenses, each of which focuses light on the dome ceiling to show a very crisp, realistic night sky. In fact, as the planetarium gears up its fundraising to replace the aging projector in the next few years, Creighton said, they will choose an updated optomechanical projector.

“But what really makes the UWM planetarium special,” she said, “is there’s an astronomer describing what the audience is looking at in 3D. Live programming that’s interactive and accessible is hard to come by. Our best communication happens in person rather than just popping in a video.”