To get to work some days, Dr. Jodi Cooley must put on full mining gear, ride an industrial elevator 1.2 miles underground, walk a half a mile through a working nickel mine, take a shower, and change all of her clothing so she doesn’t contaminate the clean lab.

It’s an unusual commute, but then, Cooley has an unusual job. She’s the executive director of SNOLAB, an enormous underground research facility in Sudbury, Ontario, Canada. There, scientists from around the world work on experiments that will help us better understand the building blocks of the universe.

“I work with people who are motivated by the fact that what they do is really awesome, that they’re working with people who are leaders in the world for the type of research they do, and they’re trying to do things people have never done before,” Cooley said.

As the head of SNOLAB, Cooley is responsible for guiding a staff of 131 employees, plus visiting scientists, to fulfill the institution’s vision: “To be a leading laboratory in deep underground science, hosting the world’s most advanced experiments that provide insight into the nature of the universe,” she explained.

That means she works with the Canadian and Ontario governments to secure funding and resources for SNOLAB. She coordinates international teams of scientists who want to perform experiments in SNOLAB’s underground lab spaces. She works with the scientific community to make researchers aware of the lab’s capabilities, and she’s responsible for the health and safety of each employee who works there.

The lab in the mine

SNOLAB is located in Creighton Mine, a working nickel mine operated by Vale Limited; the facility is in a now-depleted area of the mine away from regular operations. It’s a major research facility in Canada, much the same way Fermilab or Argonne National Laboratory are in the United States. And it’s enormous.

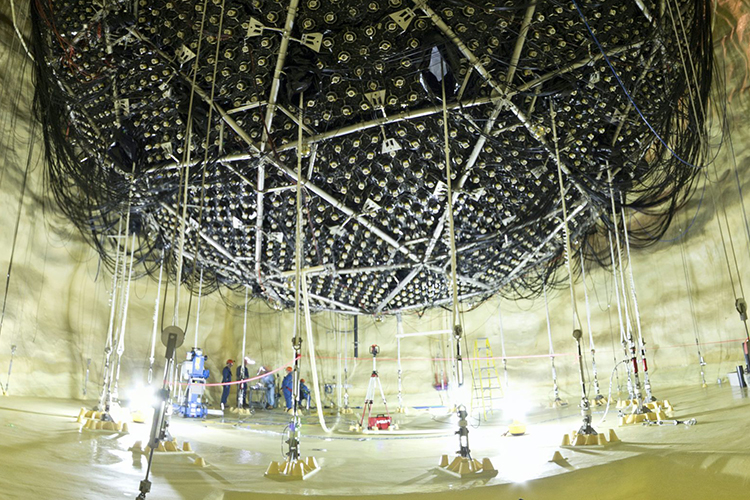

“The square footage of the floor space is 5,000 meters squared, but that doesn’t tell you the whole story of the lab. It’s the volume you want to think about,” she said. SNOLAB boasts three large underground caverns in which scientists do experiments; the biggest is as tall as a 10-story building, and the other two aren’t far behind. SNOLAB also boasts a chemistry wet lab and assembly space on surface, along with modern offices, meeting spaces and an auditorium.

Being deep underground means that SNOLAB’s clean rooms are shielded from the everyday background radiation on the Earth’s surface. This shielding from cosmic rays is essential to detecting extremely rare subatomic particle interactions that is the core of SNOLAB ‘s research program.

Scientists – those employed at SNOLAB and those visiting to perform their experiments – are conducting research in some interesting areas.

The lab currently has 24 experiments in various stages of development. Some explore the nature of a subatomic particle called neutrinos, others examine the effects of varying radiation levels on biological matter, some explore quantum computing. But most of the experiments revolve around dark matter. That’s Cooley’s particular area of expertise.

Dark matter is a unique type of particle because scientists can’t see it, even though they’ve found evidence that it exists.

““The fact that the Milky Way galaxy is rotating and the stars at the edge of the galaxy, including ourselves, are not flying off into outer space is because there are some particles there that are providing extra gravity that act like the glue that keep us rotating around the black hole at the center of our galaxy,” Cooley explained. “We know (dark matter is) there, but it’s not luminous. We can’t see it with our eye. We can’t detect it even with our X-ray telescopes. … We’ve only been able to observe it through the effect its gravity has.”

Being a part of this innovative research is exciting because the discoveries made at SNOLAB may help reveal some of the fundamental building blocks of the universe. Cooley said the lab’s work has captured the interests of not only scientists, but also the Canadian government as well: Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau is rumored to want to visit SNOLAB because “he’s a big science geek,” Cooley joked.

UWM paved the way

Cooley loves working with the dedicated scientists and staff at SNOLAB, but her favorite part of the job is getting to learn about and advocate for so many fascinating areas of science. Cooley loves to learn. It’s why she couldn’t make up her mind when she was attending UWM. She tried five different majors and was in her fifth year of college before she found her feet in the Physics Department.

“I started hanging out with more physicists. I was like, you know what? This seems kind of fun. I think I might want to go to graduate school for physics,” Cooley recalled.

And she did. As she majored in applied mathematics and physics at UWM, Cooley did research on rapidly rotating neutron stars under the mentorship of Distinguished Professor (Emeritus) John Friedman, and then attended UW-Madison to earn a PhD in astrophysics. Her research focused on a project called AMANDA – the Antarctic Muon and Neutrino Detector Array.

“And yes, I have been to the South Pole,” Cooley laughed.

She held postdoctoral positions at MIT and Stanford before landing a faculty position at Southern Methodist University, where she taught for 13 years before taking over as the director of SNOLAB last year. She credits UWM for encouraging her love of learning and for giving her the leadership skills she uses each day.

“When I look back at my time at UWM, I can’t tell you how much it meant to me,” Cooley said. “If I had gone to another school … I don’t think I would be where I’m at today.”

That’s underground, in a mine, at a laboratory on the cutting edge of physics discoveries.