Herbert Hoover is, for many Americans, synonymous with the Great Depression. What is less well-known are his successful careers as a mining engineer and as an official in the administrations of Woodrow Wilson (as director of the U.S. Food Administration) and Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge (as secretary of Commerce) prior to his own election in 1928. In his new book, “Herbert Hoover: A Life,” Glen Jeansonne, professor of history at UWM, argues that Hoover’s activist Republican progressivism puts him somewhere between today’s liberal and conservative philosophies.

As secretary of commerce, Hoover took a sophisticated but humane view of the U.S. economy. As biographer Kendrick Clements notes, “Philosophically, he believed in limited government and volunteerism, but temperamentally, he inclined to government activism and strong leadership.” Hoover intended to balance the interests of capitalists, labor, and consumers, mitigate poverty, ease the hard edges of competition, and help raise the standard of living for all Americans. Especially concerned with the status of the working poor, he envisioned a safety net for the indigent, but one that was not wholly constructed and implemented by the government.

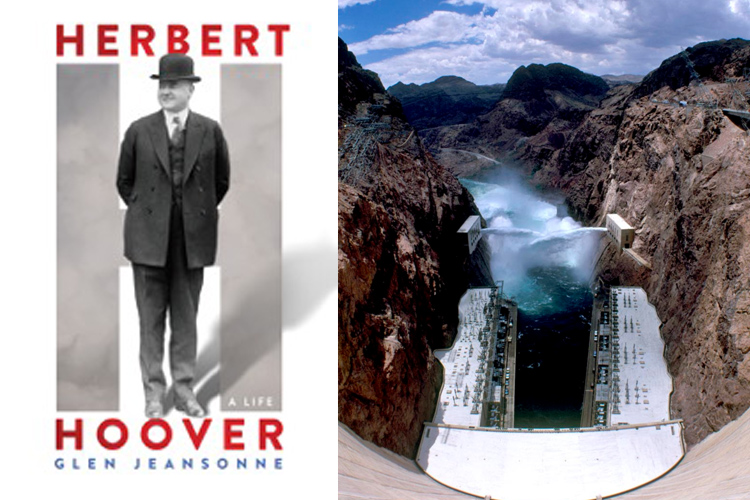

Taking a large view of what had been a modest office, Hoover was soon an octopus at the center of government, his tentacles probing into every nook. Every important component of the executive branch seemingly had an umbilical cord attached to the Commerce Department. He generated ideas and dispatched his assistants to every American state and to far corners of the globe to implement them. Hoover devised a well-rounded, all-inclusive program aimed at each major sector of the economy. Commerce quickly became the most efficient department in the cabinet, perhaps in the entire government. Hoover performed many duties that fell between departments or within other departments, or were outside of government entirely, chairing numerous government and quasi-government committees and commissions. Among his committees were the Colorado River Commission, which planned a dam on the river at Boulder Canyon, ultimately named the Hoover Dam. He continued to administer the American Relief Administration and planned a seaway to connect the Great Lakes with the Atlantic Ocean via the St. Lawrence River. The necessary pact with Canada was not ratified by Congress until the Eisenhower administration.

By the end of 1921, Hoover had established himself as one of the dominant members of the administration.

********

America’s prosperity during the 1920s was energized by technological marvels, some made possible by inventors such as Thomas Edison and Henry Ford, both friends and admirers of Herbert Hoover. The vibrant economy was driven by electrically lighted homes, telephones, motion pictures, and automobiles; the latter quite literally propelled the economy forward down country lanes and city avenues. Hoover was a booster of all of these innovations and facilitated the development of several of them. Together, they transformed America. While Hoover was amplifying radio during 1927, he also became the first American public official whose face, along with his wife’s, was transmitted by infant television from his office in Washington to the headquarters of the American Telephone and Telegraph Corporation in New York. Hoover considered picture broadcasting a pathbreaking achievement, although telecasting on a commercial scale did not materialize until after World War II. At Commerce, Hoover eased the task of inventors by eliminating paperwork needed to acquire patents and accelerating the process.

Captivated by technology, Hoover envisioned a great future for aviation in America, a nation of vast distances with many people and products to transport. Once commercial flight became faster and more reliable than railroad travel, he knew, it would quickly supplant rail for long-distance passenger service. In the short run, it could speed delivery of freight and mail, while pilots who gained experience in commercial flight would become valuable military assets. Within the Department of Commerce Hoover created an Aeronautics Division, which raised standards for airline safety, including the training and licensing of pilots. America, which lagged behind Europeans in aviation at the beginning of the 1920s, soared past the Old World by the end of the decade. Hoover employed the leverage of airmail contracts as an indirect inducement for rapid, reliable development. The Bureau of Standards conducted research on air transportation, and the commerce secretary obtained a $2.5 million grant from the Guggenheim Foundation for research into air travel. Hoover plotted out routes from New York to San Francisco via Chicago, and envisioned air trade with Latin America. He promoted the achievements of aviation pioneers such as General Billy Mitchell, who sought better air defenses; Admiral Richard E. Byrd, who flew over the North Pole in 1926; and Charles A. Lindbergh, who in 1927 became the first person to traverse the Atlantic while piloting solo. Hoover brought a child’s delight and a visionary’s anticipation to the future of the airways, and he was determined that America would lead the world in aviation during peace and war.

During the 1920s, the automobile was rapidly winning the race for dominance of transportation. Yet the nation’s infrastructure was unprepared for the impact of millions of primitive cars and trucks clanking along dusty roadways. Mounting accidents and fatalities, as well as urban traffic congestion, concerned Hoover. Commencing studies of automobile and highway safety, he convened meetings of experts and public officials and encouraged them to adopt voluntary guidelines in the absence of authority to enforce laws affecting intrastate transportation. At the outset, most roads were unlabeled, with few posted speed limits and little uniformity. Hoover recommended standardized shapes for signs, speed limits, safe highway dimensions, and other measures. Most states and major cities adopted the codes following a National Conference on Street and Highway Safety convened at the Commerce Department during the spring of 1924. Hoover studied methods of reducing accidents, including zoning laws to minimize city congestion, wider streets to permit ample parking, and the location of shopping centers with spacious parking lots outside the heart of the municipality. He suggested construction of highway arteries bypassing downtown areas, widening of avenues to ensure pedestrian safety, pedestrian isles, traffic circles, designated unloading spaces, elimination of taxicab “cruising,” and the prediction of areas of urban growth in order to anticipate density of automobile traffic. In these insights, as in other attempts to manage new technology, Herbert Hoover was on the cutting edge of his times.

Reprinted from Herbert Hoover: A Life, by Glen Jeansonne, with permission from NAL, copyright 2016.