That shelf of cookbooks in your kitchen might actually be a library of political declarations in disguise.

In fact, said UWM political science professor Kennan Ferguson, even that collection of notecard recipes from your mother’s church friends makes a political statement about in-groups and community identity.

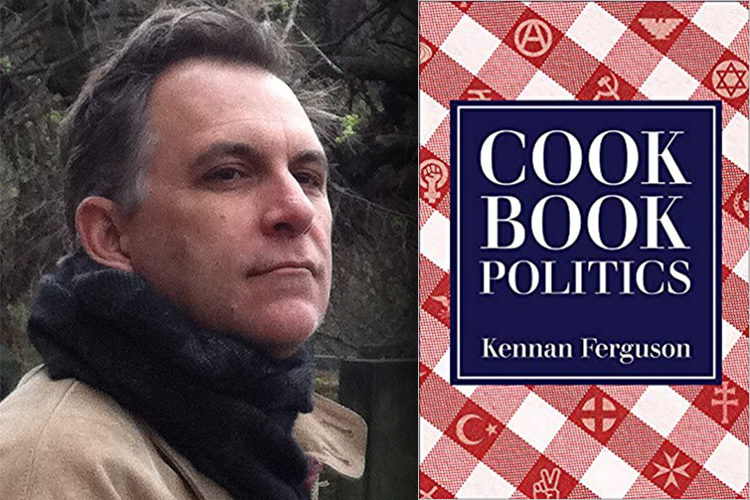

Ferguson is a political philosopher and the author of “Cookbook Politics,” a new book exploring the ways in which collections of recipes actually have a governmental and societal impact. Ferguson was inspired by the work of theorist Jacques Rancière, who argues that politics is the distribution of sensibility – “what we see and don’t see, who counts and who doesn’t,” Ferguson said.

“I was intrigued by the sensibility part of that. What does it mean to have a distribution of the human senses? The cookbook looked like a great way to explore that question in a way that other (philosophers) were ignoring.”

Although a guide to soul food or a how-to in Mediterranean cuisine may not sound like it, Ferguson’s book identifies five ways in which cookbooks are actually vehicles that have not only been shaped by, but also have an impact on, political ideologies and movements.

Cookbooks are tools of nation-building

Thousands of cookbooks explore cuisines from nations around the world. These guides are just as much a way to showcase regional food as they are to distinguish a country’s culture and political identity.

“Once a nation becomes independent, nearly always within 10 years, those nation-states have a cookbook,” Ferguson noted.

Take Belize, for example. The former British colony gained its independence in 1981.

“Within 10 years they had developed three national cookbooks,” Ferguson said. “People who come to Belize want to eat Belizean food, whereas back when it was a colony, there was English food, Chinese immigrant community food, the Garifuna people’s food, Mayan food – those are all distinct cuisines. A cookbook has to unify them all in some way.”

Cookbooks shape our understanding of international relations

Think of the food in France. Picture baguettes purchased at the corner bakery, soft cheeses with fine wine, and dishes cooked with rich cream and butter. It’s an image almost every American holds in their head, even if they have never been to France.

It’s all thanks to Julia Child and her famous cookbook, “Mastering the Art of French Cooking.”

“Most people in international relations (talk) about President Eisenhower and Charles de Gaulle (French president from 1959-1969). In some ways, what those men did is a lot less important than what Julia Child did, which was to give us an image of France,” Ferguson said. “For Americans, her achievement has been much more long-lasting than almost anything that de Gaulle or Eisenhower did.”

Cookbooks delineate social groups

The ladies of the First Baptist Church of Spence, Iowa, thought they were just collecting each other’s recipes to publish in a book for the congregation, but actually, says Ferguson, they were curating content that defines their collective social standing.

Community cookbooks have long gathered the culinary knowledge of traditionally women-centric organizations, including church auxiliaries and synagogue sisterhoods. The books help define who is included in the group and showcase the ways in which traditional recipes are transmitted and handed down, both to community and family members.

But, Ferguson added, these collections can be just as much about redefining identity. Take “The Settlement Cookbook,” for example. The most popular guide in its day, the cookbook was compiled by Lizzie Kander, a Milwaukee woman who was part of an organization that taught immigrants to assimilate to America in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

“Part of that process was to teach them how to cook American (food) instead of trying to make these traditional Jewish recipes from the Old World,” Ferguson said. “There’s an assimilationist ideology in both the settlement movement and the cookbooks that came out of it. Some of it may have to do with even undermining the religious identities. You teach Jewish women how to cook pork because that’s an American thing. Lizzie Kander, who was Jewish herself, had a lot of pork and shrimp recipes in the book.”

Cookbooks reflect political ideologies

In the early 20th century, the Futurism movement sprang to life in Italy. Closely tied to the country’s fascist political parties, Futurists idolized speed, technology, and innovation in all things, including their food.

“They wanted people to stop making their own bread, and to instead buy industrially produced bread,” Ferguson said. “They wanted people to eat food that stimulated them in war-like ways – like salami dipped in coffee. There’s a recipe for chicken made with ball bearings, so you can ‘taste the steel’ of the future.”

It was in a Futurist cookbook that Ferguson found his favorite recipe he encountered during his research: “A carrot with eggplant legs that represents a university professor, and you’re supposed to devour the entire thing ‘without ceremony.’”

Others in Italy pushed back against the Futurists and later gave rise to “slow food” movement, which is today still tied to Italian culture, economics, and tourism.

Cookbooks as a format are democratic

That’s democratic with a small “d,” Ferguson noted.

“It doesn’t tell you what you have to do; it is an invitation to follow authority in a way that you desire. You might just cross out a line that you don’t like or write in something that you want to change. … Usually we don’t even read most of the book. It’s a kind of democratic authority that is invitational instead of demanding.”

There’s a substantial body of academic work analyzing cookbooks and food. In addition to exploring scholarly articles, Ferguson researched his book by visiting Harvard University’s Schlesinger Library, which boasts an enormous collection of published cookbooks, and Texas Women’s University, which has collected a trove of community cookbooks.

While he was researching, Ferguson worried that he was exploring a dying genre. Many people rely on social media or Google to find recipes, and as at-home dining turns digital, cookbooks have the potential to fall by the wayside.

But, said Ferguson, “Cookbooks haven’t actually stopped selling, and I think that’s because people look to them inspirationally as well as instructionally. There’s a pleasure to reading a cookbook with beautiful pictures that (give you) an insight into somebody or a region or particular history.”