Introducing ‘Hoot’!

On April 17, 2021 the first ever Titan Arum bloomed at the UWM Biological Sciences Greenhouse. The Titan Arum, or Corpse Flower, is recorded to have the largest, and one of the smelliest, inflorescences of the plant world.

Convention dictates that an individual Titan Arum plant is named upon its very first bloom. We’ve affectionately named ours ‘Hoot’, in honor of Dr. Sara Hoot. Read more about Dr. Hoot here. Currently, UWM’s Biological Sciences instructional collection maintains nine individual Amorphophallus titanum plants.

Life Cycle of the Titan Arum

Titan Arum corm just starting to emerge from dormancy

The Corpse Flower, or Titan Arum, is native to the rainforests of Sumatra in Indonesia. They are uncommon in the wild and are under considerable population pressure as their native habitats are rapidly being destroyed, primarily due to illegal logging and land conversion for agricultural use. As of 2020, A. titanum is listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Titan Arum leaf viewed from below, courtesy of Dr. Karron

A. titanum grows from a corm, which in older specimens have been documented weighing up to 198 lb. From the corm, a single, umbrella-like, individual leaf composed of a trunk-like petiole topped with an array of leaflets will emerge, photosynthesizing and storing food for 9-12 months (in our greenhouse).

The yellow-leafed plant is a Titan Arum starting to senesce. Note two other large Amorphophallus specimens in the background.

Next, the leaf will senesce (die back) and the plant will go dormant. The dormancy period of our specimens varies from 2-5 months. The process then repeats itself until the plant sends up a flower bud instead of a leaf. In cultivation, this will average 7-10 years after seed germination. Blooming is considered a very rare event in cultivation and even more rare in the wild. The average A. titanum bloom grows ~6.5 feet tall, making it the largest unbranched inflorescence in the world (the largest branched inflorescence belongs to Corypha umbraculifera, the talipot palm).

‘Hoot’ spadix emerging

Alas, the Titan Arum is not the world’s largest individual flower. This title is held by Rafflesia arnoldii, another stinky flower, also named Corpse Flower. A titanum‘s bloom is a flower structure consisting of a tall spadix (spike) wrapped by a spathe (a frilly modified leaf). The flowers themselves are quite small and form a small cluster at the base of the structure. The male flowers are located on the top of this cluster and release pollen, and the female flowers are located on the bottom of the cluster.

Wendy Semski (Karron Lab) poses with ‘Hoot’

While the foliage is stunning, it is the fragrance, the smell of decaying animal flesh, from this inflorescence that gives the A. titanum its namesake of the “Corpse Plant”. As evening approaches, the female flowers open, thermogenesis begins and the spadix heats up to ~98.6°F, volatilizing its pungent scent, trying to entice pollinators such as carrion beetles, flies, and other insects that are active at night. Dr. Kite (Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew) found the key odorants to be sulfides; dimethyl trisulfide (a rotting, animal-like sulfury odor) and dimethyl disulfide (a garlic-like smell).

Close-up of the Titan Arum flowers

Other compounds present include isovaleric acid, (the smell of sweaty feet) and methylthiol acetate (an unsavory blend of moldy garlic and rotten cheese).

The next day, the male flowers open. Within 24-48 hours of maturity, the smell dissipates, the flower structure begins to wilt and eventually collapses, having expended most of its energy. Trimethylamine is released (the source of that lovely rotting fish smell), and hopefully the plant had a successful pollination event!

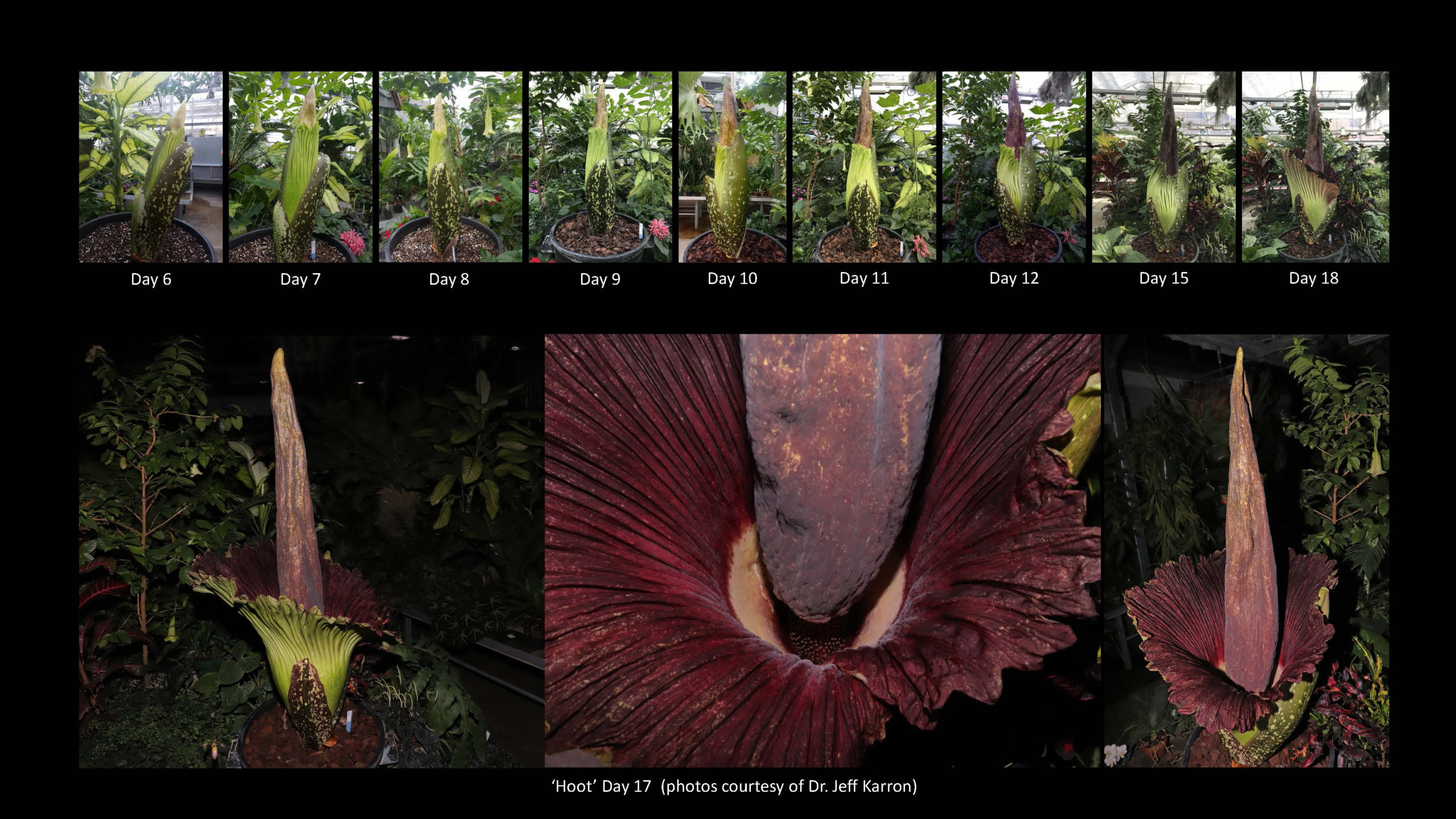

UWM Biological Sciences Titan Arum, ‘Hoot’

The corm weight of ‘Hoot’ is estimated at about 12 lb, smaller than normal for an initial bloom event. At last sprout, Hoot’s petiole was nine feet tall with a circumference of 16 in. at the base.

About Dr. Sara Hoot

Dr. Hoot is a systematic and evolutionary botanist who has spent more than 30  years of her life in formal study of plants and their evolutionary relationships. For more than 20 of these years, she taught in the classroom and helped to train the next generation of systematic biologists to study and describe the diversity of life. Her keen attention to detail in nature, however, is a lifelong pursuit; from her childhood in Eastern North America to her current home and garden in the Milwaukee area, she has studied and cultivated her love of plant life around her.

years of her life in formal study of plants and their evolutionary relationships. For more than 20 of these years, she taught in the classroom and helped to train the next generation of systematic biologists to study and describe the diversity of life. Her keen attention to detail in nature, however, is a lifelong pursuit; from her childhood in Eastern North America to her current home and garden in the Milwaukee area, she has studied and cultivated her love of plant life around her.

Sara’s appreciation of the beauty of plants is infectious, and her students are trained to use a rich set of approaches for inferring evolutionary patterns, and hence gain a better understanding of the process and tempo of evolution across space, time, and lineages. Sara has provided key insights into the evolutionary history of flowering plants and lycophytes by incorporating molecular and morphological data of extant plants with fossils and historical geography. Her work on the systematic relationships and timing of key divergence and diversification events among species of Anemone and other members of the buttercup order, Ranunculales—including well-known and less familiar families of herbaceous and woody plants such as buttercups, poppies, bleeding-heart, fumitory, barberries, and moonseeds—is particularly notable, evidenced by many international collaborations and her status as an expert in these plant lineages. Her dedication continues long into retirement, with her continued association with the UWM Biological Sciences Greenhouse.