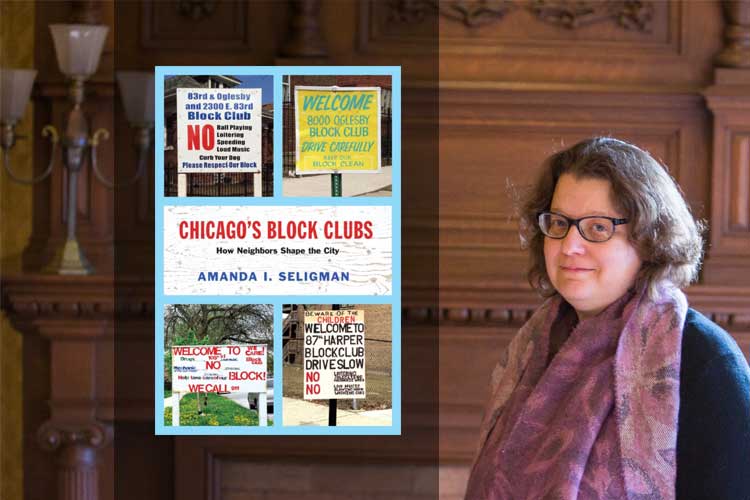

When Amanda Seligman, professor of history at UWM, was investigating the transitions of Chicago neighborhoods, she encountered the phenomenon of the Chicago block club. She found that the small battles waged by these organizations are vital to understanding the city’s political and social history. In this excerpt, she discusses an example of the work of the block clubs: repurposing chronically vacant lots.

Tracking down owners was a difficult task, but block clubs could not simply co-opt abandoned lots and repurpose them. They had to secure the owners’ permission first. Sometimes the owners refused. The block club at 2900 West Walnut Street proposed to rent a vacant lot for a play area, using funds donated for the purpose. The owners declined the club’s offer, citing the desire of tenants in adjacent buildings not to be disturbed by children’s games. In other cases, block clubs sought help from aldermen and from the Chicago Park District.

Hyde Park scholars Herbert Thelen and Bettie Sarchet noted that a community-sponsored playground required maintenance and periodic equipment replacement, as well as the effort of construction. Surrounding informal playgrounds with fencing kept children from running into traffic. To pay for a fence around a vacant lot on their block, members of the 4400 Adams Block Club conducted a small fundraising campaign, netting more than one hundred dollars from five-dollar pledges. The group that organized a tot lot for the vicinity of South Drexel and 56th Street issued regulations for its members. Residents could access the locked tot lot using a combination lock, but children were not permitted to play in it without adult supervision. Gendered assumptions informed postwar tot lot construction and use. According to Thelen and Sarchet, “usually, a group of fathers got together to clear the lot and level it off. Fencing and other equipment was built by father’s groups. A mother’s committee was organized to provide supervision, with two mothers on duty whenever the lot was open.” A publicity photo for an exemplar project, however, showed a man helping a child down the slide.

On blocks with few small children, building a tot lot was not the most sensible use of block club resources. Transforming a vacant lot into a garden presented an alternative strategy for local beautification. Urban agriculture has a long history that scholars are just beginning to unpack. Chicagoans became familiar with urban gardening on a broad scale during World War II, when the Office of Civilian Defense (OCD) encouraged city block clubs to join other Americans in tending “victory gardens.” The OCD matched volunteer gardeners with plots of nearby land designated for food cultivation. Decades after the war’s end, urban vegetable gardening enjoyed a revival.

Like a tot lot, a garden improved a street’s aesthetic quality and occupied older children who enjoyed working in dirt. The nutrition offered by fresh vegetables also had the potential to improve the health of block residents across ages. With these three goals in mind, the 15th Place Block Club, energized by the indefatigable Faith Rich, devoted enormous efforts to community gardening. Its gardening project began in the late 1960s, with “a veritable madness of buying dirt and planting,” and evolved by the mid-1980s into a large-scale project. To support their work the club members wrote a letter to Mayor Harold Washington petitioning for help from a “city garden crew with access to heavy equipment for digging out the bricks prior to preparing the soil for planting.” In the intervening two decades, the gardening project taught the club’s participants much about growing grass and vegetables; revealed pollution in their physical environment; brought them into contact with local proprietors, property owners, and city officials; and cultivated community life.

The 15th Place Block Club’s project started in 1968 when the club’s president, Pearlie Robinson, became concerned that “we have been planting either no grass or just poor weak grass which quickly gets trampled by the children and does not come back the next year.” Residents were discouraged in their efforts to get property owners to establish perennial grass. One janitor never followed through on his promises, and “there was nothing in the leases o[r] [c]ustoms to make the landlords plant grass.” The owners of nearby buildings experienced the same difficulty, explaining that “it [wa]s useless to plant [grass] because the children will wear it off anyway. When they did supply grass seed it was annual and had of course to be planted over again each year.” Nonetheless determined to green the environs, Robinson asked the resourceful Rich if she knew how to find what she called “‘Come Back’ grass.” The block club took the task upon itself, purchasing grass seed with its own funds and committing to the labor of tending it. Residents turned out twice a day for two weeks to water the initial plantings. The club “gradually established perennial grass” over the next several years, developing “our goal of grass all around the block” by seeding all the lawns, “something which was generally thought to be impossible.” By 1973, some of the local building owners had agreed to purchase dirt for the project, although one such donated lot of soil left “even more stones than there were originally.”

Rich wrote to her sister that the grass wrought “a great change.” It not only improved the appearance of the area the block club officially tended, but also provided the neighbors with an incentive to transform their home environments— even if they were not property owners. Rich explained, “In the house next to us one of the tenants who had never done anything about grass before suddenly bought flowers, dug up part of the grass and put the flowers there, planted grass around the side of the house. She even set up a bird bath. If this keeps up we will be practically suburban.”

At roughly the same time as the grass project, the block club also began encouraging neighbors to plant food crops. Faith Rich and her husband, Ted Rich, had a vision “to cover Chicago’s west side with organic gardens on the vacant lots.” Their model was the 3300 block of West Flournoy Street, where several residents kept gardens in their backyards and “many vegetables were donated to block club affairs.” For her part, block club president Pearlie Robinson was “dreaming of the country in the city, where fruit and nuts grow in the yards and in the parks and the children can pick and eat as they did the persimmons and pecans when she was a girl.” Tending lawns and several gardens was enough work so that the two activities sometimes competed for attention, but club members persevered.

One of the first obstacles to gardening on vacant city lots was the poor quality of the soil. The club tried to remedy its deficiencies. Faith Rich attempted to create compost with enough nutrients to grow healthy plants. She buried her garbage next door to her home in the hope of helping a neighbor’s vegetable garden. The block club voted to include leaves in the compost, since the addition of yard waste to kitchen refuse makes for more fecund soil. Rich asked the Chicago Department of Streets and Sanitation and the Chicago Park District to contribute dead leaves to the effort; because the block abutted Douglas Park, one of the city’s largest parks, suitable leaves were not far away. But she found that they “could not dump leaves on private property without specific permission from the city.” The city refused to help identify the property owners so that the block club could seek their cooperation. In one case, a frustrated Rich later discovered, the city itself owned the lot. Further, when the block club members had their soil tested in 1986, they found excessive levels of cadmium contamination. This discovery sent them to the University of Illinois Cooperative Extension Program for information about which vegetables could be safely grown and consumed. The group also took advantage of an offer from the Metropolitan Sanitary District of Greater Chicago for free sludge. As a result of this difficulty in obtaining soil good enough for gardening, the 15th Place Block Club urged the city to update its laws so that building wreckers would be required to leave three inches of soil on the site of a wrecked building.

Despite the troubles with the soil, the 15th Place Block Club ultimately supported five vacant lot gardens on its block. Rich wrote, “At first most of the people thought I was crazy and only the children worked with me, picking up the stones and planting the seeds. But then some things grew, many more began to be interested and a few actually worked so that last year I did hardly anything.” The gardening effort attracted several older men on the block. Rich described them in loving, wry detail in a letter to her sister:

“Two men, both tenants, in the Kedzie building, a 24 apartment building on one corner of our block, became interested in the garden and go out there as early as six o’clock in the morning I am told. They spaded it up and planted it . . . One of the men doesn’t really do any work because he has a bad heart and is not supposed to lift a finger or do anything but he contributes companionship for the other man and a great many ideas, many of them inconvenient. He also goes out and buys things for the garden. He says he often spends much more for liquor and why shouldn’t he put the money in the garden instead. Why indeed?”

The garden received tending from “Mr. Fane . . . a former Mississippi farmer who has some disability and cannot work.” He told Rich that he was “delighted” that the block club’s garden provided him an opportunity to spend time outside. Fane even devoted himself to the garden during the winter, starting plants in his basement for early spring transplantation. The gardeners received additional help from “Mr. Robert Simms, age 12, a student at Johnson School, [who] came over with his father’s tractor and disked and leveled the garden.” Perhaps more than other sporadically offered block club programs, gardening depended on the continuous energies of participants to prepare, plant, weed, and harvest. In 1987, the 15th Place Block Club debated inconclusively on whether to turn one of its collective plots over to a church for a parking lot, because Robinson, the club’s president, “said she could no longer be responsible for a garden.” A fallow garden presented as much potential trouble to a block as an abandoned building or an unused lot.

Reprinted with permission from Chicago’s Block Clubs: How Neighbors Shape the City, by Amanda I. Seligman, published by the University of Chicago Press, copyright 2016, by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.