In Milwaukee County, more than half of African-American men in their 30s have served time in state prison. Researchers say this pattern of black male incarceration tracks historical lines of racial and class segregation in the city.

Now a team of UWM scholars is focusing on the ways in which this mass incarceration contributes to health inequities.

Now a team of UWM scholars is focusing on the ways in which this mass incarceration contributes to health inequities.

Their project, “Transforming Justice: Rethinking the Politics of Security, Mass Incarceration, and Community Health,” is funded by one of two 2014-15 Transdisciplinary Challenge grants through the Center for 21st Century Studies (C21).

“We want to look at that issue from a public health perspective…how mass incarceration is disrupting families and social ties within the neighborhoods,” says Jenna Loyd, assistant professor of public health policy and administration in the Joseph J. Zilber School of Public Health. “We want to look at the geography and history. How is mass incarceration in Milwaukee tied to racism? What are the different impacts on men and women?”

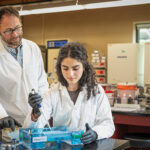

Other members of the interdisciplinary team include Lorraine Halinka Malcoe, associate professor of epidemiology in the Zilber School; Robert S. Smith, associate professor of history; Anne Bonds, assistant professor of geography; and Jenny Plevin, program director of doc|UWM in the Peck School of the Arts.

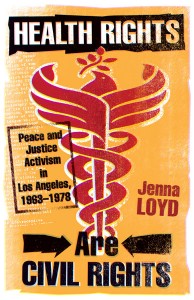

Loyd has already explored the impact of history, geography and politics on public health in her new book, “Health Rights are Civil Rights: Peace and Justice Activism in Los Angeles, 1963-1978.” The book traces how peace and social justice activists – particularly within the Black Freedom Movement, Women’s Movement, Welfare Rights and peace movements – worked to create accessible health care and healthier living conditions in Los Angeles.

One of the things that this history helps us think about, says Loyd, is how the demands of the Civil Rights Movement for economic justice, including jobs creation and an adequate income for all, remain unmet and were undermined nationwide through an embrace of law-and-order politics.

The C21 transdisciplinary project Loyd and Malcoe are working on will bring together academics and people who have experienced incarceration to pose new and different questions on mass incarceration and prevention in public health.

“The idea of this type of community-based participatory action research,” says Malcoe, “is not to assume academics have all the answers.”

The research team, including UWM graduate students, will plan a series of workshops, working with community members to facilitate conversations about how incarceration affects mental health, exacerbates problems of historic inequity and segregation, and adds to a climate of violence and ongoing trauma. Individual community members will use digital video to document their own experiences, and help with making a collaboratively edited documentary.

This type of community-engaged public health research is key for shaping shared solutions, according to Magda Peck, founding dean of the Zilber School of Public Health. Researchers like Loyd, Malcoe and their colleagues explore more than individual behavior as a determinant of health. They’re studying the socioeconomic processes and policies shaping where people live and work, and the impact they have on their health and well-being.

The Transforming Justice project will use these insights from public health to focus on mass incarceration as a health harm, according to Malcoe and Loyd.

“Creating health justice will mean shifting explanations for mass incarceration away from so-called ‘problem neighborhoods’ and onto local, state, and federal policies. It will also mean grappling with and transforming histories of racism and geographies of segregation. Our project aims to transform research and conversations on criminal justice to foreground social justice,” says Malcoe.

“We want our students to understand all the different ways they can think about economic or social issues, and see them through a public health lens,” adds Loyd.

Three new master’s degree tracks in public health that start this fall – epidemiology, biostatistics and public health policy and administration – are designed to prepare public health leaders to look at the social and structural determinants of health and approaches to overcoming inequities.

“With projects like the study of the impact of mass incarceration on public health,” says Loyd, “we are trying to shift the conversation, create possibilities for policy shift.”

Both Loyd and Malcoe will be teaching courses that are part of those tracks. (Scholarships are available for these programs through a gift from the Zilber Family Foundation. See information on the scholarship.