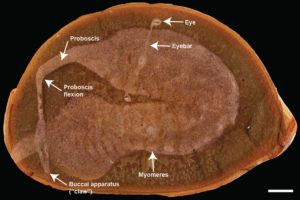

Fossil remains have helped paleontologists to determine that an extinct animal colloquially known as a Tully monster was one weird-looking organism. Soft-bodied and aquatic, it had a long proboscis, similar to an elephant’s trunk, extending from its body that ended in a toothed mouth resembling a crab claw. Its eyes were set on the ends of a slim, rigid bar.

The organism, Tullimonstrum, is so bizarre it has defied classification.

Scientists haven’t been able to agree on whether the Tully monster, which lived in shallow coastal waters 300 million years ago, was a vertebrate. While that term usually refers to an animal with a spine, there are a few vertebrates that do not have any bones, said paleontologist Victoria McCoy.

Establishing the Tully monster’s biological classification would prove whether it was a jawless fish – similar to a lamprey – or more like a large worm.

Now, McCoy, a UWM visiting assistant professor of geosciences, and collaborator Jasmina Wiemann at Yale University have found a way to extract telltale molecular information contained in the fossils that distinguishes between vertebrates and invertebrates.

The composition of structural tissues, such as cartilage, that give shape to a body is distinct in the two groups.

Invertebrates have structural tissues that contain mostly chitin, a fibrous substance that is the main component of the exoskeletons of insects. But vertebrates’ tissues are comprised of primarily of protein.

McCoy and Wiemann used Raman microspectroscopy to identify the components of this tissue that partially decomposed before the fossil formed. This technique measures the energy in a microscopic sample – including the energy’s respective wavelength – which serves as a chemical signature. They analyzed brown stains on the fossils where the color told them minute amounts of organic material remained.

In addition to the Tully monster fossils, the researchers conducted the molecular analysis on a variety of other fossils found at the same site, including invertebrates like worms, arthropods and mollusks.

“We looked at many different tissues in the Tully monster, and all of them had a chemical fingerprint of fossil proteins, and none had a chemical fingerprint of fossil chitin,” McCoy said. “Now we have a much stronger argument in favor of a vertebrate affinity than the previous morphological arguments.”

The vertebrate/invertebrate debate has raged since the fossils first turned up at a well-known fossil bed 50 miles southwest of Chicago in 1958.

Previous arguments for either side have been based on morphology – the animal’s appearance, said McCoy.

As a graduate student, McCoy herself was part of a group that published a paper in Nature in 2016 arguing that the creature was a vertebrate based on a study of its physical features.

“The morphology is so strange and difficult to interpret that I didn’t think studying that in more detail would resolve the question,” she said. “So I wanted to come back and study it from a different angle.”

The research was recently published in the journal Geobiology.