In the basement of the Chemistry Building, Neal Korfhage wields a torch with careful precision. Before him, an Erlenmeyer flask fixed to a spinning lathe is getting an upgrade: three indents around its base to increase the surface area inside.

Korfhage, protected by heavy gloves and glasses that block out the intense light of the orange flame shooting from the torch, gently presses a rod into glass so hot it’s become malleable. It bends inward, and Korfhage quickly treats the groove with flame to smooth out the mark.

When all three indents are made, he rushes the flask to an oven heated to over 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit, where it will be allowed to cool slowly over the next several hours. If it cools too quickly, the glass will crack under thermal strain. Once the piece is finished, it will head back up to the chemistry labs on the floors above.

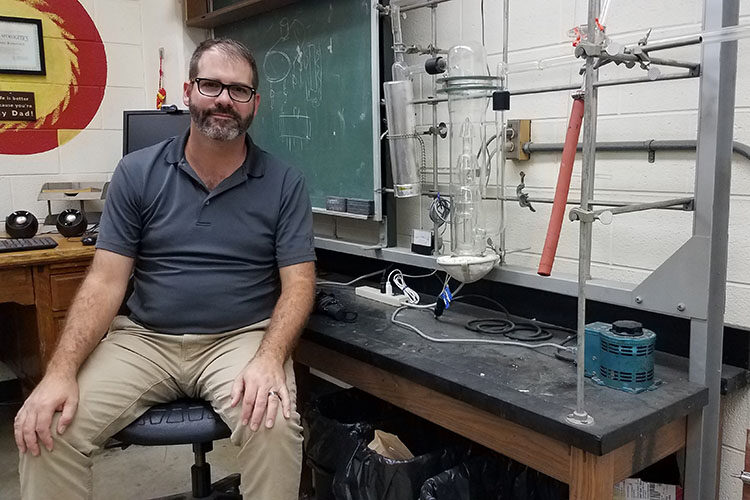

Korfhage is UWM’s staff glassblower. Working out of the Department of Chemistry, he not only repairs broken glassware from the labs above his workshop, but also creates custom equipment for the university’s chemists, physicists and biologists.

“The scientists know what they want … and they come to us and just say, ‘I need this thing.’ And we say, OK!” he joked.

Glass is the ideal material for those scientific experiments, he added. It’s mostly inert and barely reacts with anything, outside of hydrofluoric acid.

A rare glassblowing breed

Glassblowing is an art, but Korfhage mixes it with science. He is what’s called a scientific glassblower, which differs from artistic glassblowers who might make decorative pieces like stemware or chandeliers. Scientific glassblowing is a niche field where craftsmen make creations specifically for use in science research. That means anything from flasks and beakers to the vacuum chamber that Korfhage custom-made for some of the university’s physicists.

“I like to think of it as a machining support industry, mostly to chemists,” he says. “It branches out into other sciences as well. Biochemistry, for example, doesn’t like oxygen very much because it reacts with everything. We want to prevent that, so we make vacuum systems with an ultra-low vacuum.”

Eight or 10 in the country

When he says ‘we,’ Korfhage is referring to a handful of artisans around the United States. Most are employed in scientific manufacturing; Vineland, New Jersey, is something of a hub for glassmaking companies. But the industry has been shrinking, Korfhage says, with companies consolidating or being bought out since glassblowing’s heyday post-World War II.

Even rarer are glassblowers like Korfhage himself, who work and support research within a university.

“Wisconsin has two, including me,” he says. “I think that there’s probably about, maybe throughout the whole country, eight or 10 university glassblowers.”

And that’s a shame, he adds, because a good glassblower can save their institution a lot of time and money. Korfhage holds up a broken condenser that needs repairs as an example.

“One of these, brand new, is over $1,000,” he says, pointing out the crack on a component inside the hollow glass tube. “This is made by a company in Japan. That takes a lot of time for shipping (for a replacement), whereas I can fix this in a couple of business days.”

Learning the trade

Korfhage learned glassblowing at his father’s knee – or rather, his furnace. The elder Korfhage was also a glassblower who built his own workshop as an addition on their house.

“I would watch him as a kid – I would put on the safety glasses that filter out the bright orange light and I would just watch him, fascinated by him,” Korfhage recalls. He smiles as he tells of his first glassblowing project: Learning to make old-fashioned perfume bottle tops through a process called “tooling.”

When Korfhage was 15, his father took his son on as an apprentice. Korfhage later attended Salem Community College in Carneys Point, New Jersey – his father’s alma mater – where he began working toward his two-year applied science degree. Salem Community College offers the nation’s only scientific glassblowing program of study.

“Ironically, I did not graduate,” Korfhage admits. Instead, representatives from Aldrich Chemical (now Millipore Sigma) in Milwaukee swung by the college during his third semester and interviewed the novice glassblowers to fill four positions in their 12-man shop. Korfhage got an offer.

“Do I finish the Salem program and miss the opportunity of a lifetime to have a really good job before I even graduate, or do I, for the sake of the education, graduate and miss out on the job?” he muses. “I chose the job. Education is supposed to lead to the job. All I did was take a one-semester shortcut.”

But soon after he arrived in Milwaukee, UWM popped up on his radar. Korfhage met the university’s previous glassblower at an industry conference and liked the idea of being a glassblower in higher education.

“Eleven years goes by and nothing. I’m working at Aldrich, and it’s a great company for me. Then I heard from my dad, who heard that the position was open. By the time I had found out about it, it had been open for a whole year,” Korfhage laughs. “I talked to my dad on the phone: ‘Neal, I want you to get your résumé right now and drive to UWM right now and submit your résumé right now.’ And that’s what I did.”

He’s been at UWM for 15 years.

The university’s glassblower

Korfhage’s lab is dominated by the lathe and torch set up at the front of the room. Beyond it are work tables and shelves upon shelves of boxes filled with glass tubing of various sizes. Rather than make his own glass, Korfhage uses the tubing for repairs and custom projects. In another room off the main workshop sits the oven where the Erlenmeyer flask is now cooling.

On one wall there’s an old Science Bag poster featuring Korfhage and his boss, associate professor of chemistry Joseph Aldstadt. The two are dressed in period clothing in their photo; the show covered the historic relationship between scientists and glassblowers, especially as it concerned the discovery of oxygen in the 1770s.

If it sounds like Korfhage is having fun, it’s because he is. UWM is fulfilling in a way that his commercial work at Aldrich Chemical wasn’t.

“Here, I work with the people that I’m helping,” he says. “I see the people that I’m helping, and if someone needs something special made, we can collaborate on it together.”

That’s definitely a reason to raise a glass.