When it’s time to mate, female eastern gray tree frogs venture at night toward the pond, where they are bombarded by a chorus of hundreds of male frogs singing with pulsed “chirps” that differ in pitch, duration, volume and repetition. The collective serenade goes on for hours, though individual males take breaks.

“Male calling has been described as the most energetically challenging behavior of any vertebrate,” said Gerlinde Höbel, “and the competition is stiff. Males pay attention to what other males are doing, and they push themselves as far as they can.”

With so much variation to choose from, how does a female decide which she’ll respond to? The question would be impossible to study in a natural setting because of the sheer volume calls and their traits, said Höbel, an associate professor of biological sciences at UWM.

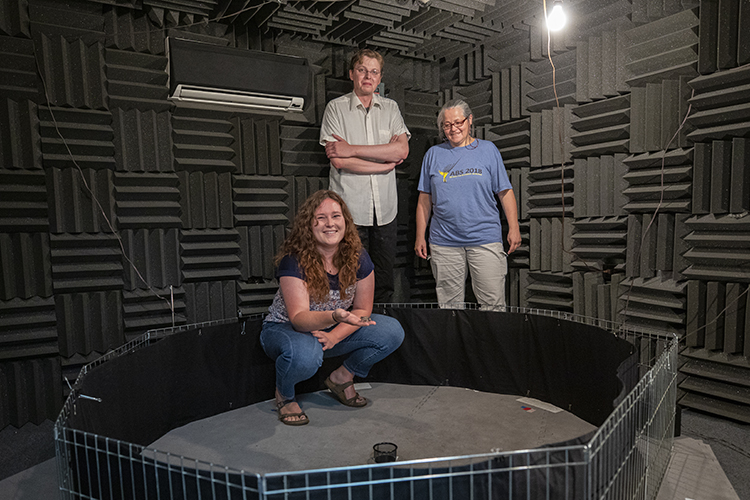

Instead, Höbel and her students bring frogs they’ve caught to an environment specifically designed for tree frog romance in the lab. Inside what looks like a large walk-in freezer in Lapham Hall is a simulated setting, dubbed the “frog arena.”

Here, Höbel and her lab members are teasing apart what the different types of vocalizations might mean and using the arena to investigate an assortment of questions about frog communication, including female preferences to calls.

The stakes couldn’t be higher: Most females will mate only once in their lives, while many males will not find a mate at all. So answers to mating behavior questions have evolutionary implications, Höbel said.

It’s the females who often drive sexual selection, a preference by one sex for certain characteristics in those of the other sex, she said.

“Much of the amazing mating diversity we see in nature – like songs, plumage color and dances – are the outcome of sexual selection by female choice. Sexual selection is one of the main drivers of biological diversity.”

Traits and tribulations

Conditions inside the frog arena can be controlled to mimic the pond. The temperature is kept at 68 degrees, and a nightlight provides just enough light. The walls are covered in acoustic foam, which prevents the sound distortions that occur indoors.

In a circular clearing on the floor, the researchers have placed small speakers around the circumference. In the center, they confine a female frog in a pod and then leave the chamber. In some of their experiments, they will expose the female to two different male calls, and then remotely lift the lid and free her to pursue her choice.

“In theory, the females will go faster toward what they consider the most sexy,” said doctoral student Olivia Feagles. “If the call is really ugly to them, maybe they wander around a little and wait for other options.”

Thanks to a camera and an infrared light in the arena, researchers on the outside can watch without disturbing the females, who don’t see infrared light.

The only missing pieces are the actual male frogs. Instead, male calls have been recorded in the field and used to program computer-generated reproductions played in the arena.

“This way, we can not only manipulate the frog calls,” Höbel said, “but also other environmental features like chorus densities by adding more speakers, or predator cues by playing predator sounds.”

Each season the lab members will run about 1,000 or more trials in the arena. This year, they gathered a bumper crop of female frogs from their natural habitat at the UWM Field Station near Saukville, where Höbel’s lab operates a second frog arena.

Reading the female’s mind

During a recent arena experiment, doctoral student Kane Stratman narrated the action from his computer screen. “The male call she was thinking about just took a break,” he reported. “And there’s a more attractive male call over there that just started up. The hypothesis is she should not wait around very long to go for it.”

After years of experimentation, the researchers know this species likes longer, faster calls on average. But there are plenty of females who like short or intermediate-length calls, Stratman said.

Decoding the mating communication may reveal why all the calls aren’t the same, he said. A more mixed bag of female preferences in the population could mean that a larger range of males will have a chance of mating, leading to a maintenance of variation in male calls.

For each female they test, the lab members graph the time she takes to make a choice with the length of her chosen call. Some show a steep curve indicating a strong preference. On others, the curve is more shallow, which means she has a preferred call, but she’s tolerant of those that are not a perfect match.

How choosey are they?

This tool is helping Feagles correlate the individual preferences of the females with the characteristics of the males they ultimately chose.

Feagles also is investigating how choosy each female is, by repeatedly lengthening the perceived distance of the call and recording how far the female is willing to travel for the more attractive call. A less finicky female is more likely to choose to mate with an ugly call that is conveniently nearby rather than searching for a more attractive call across the pond.

Memory is also a consideration, Stratman said. Another question he is exploring using the arena is to determine how long a female can remember where she heard a really attractive call before she settles for an “average-Joe call” that’s closer to her.

It’s about balancing preferences with opportunities, Höbel said.

“Mate choice is a complex affair, and females have to balance what they want – preference – and how much they want it – choosiness – with the conditions they encounter at the pond.”