While Lindsey Roddy was working as an intensive care nurse at a Milwaukee hospital, she enrolled in UWM’s College of Nursing to work on a doctoral degree. She wasn’t preparing to own a business. In fact, it had never crossed her mind.

Then, a conversation with two nursing faculty members who were involved in entrepreneurship steered her toward innovation in the nursing field. They asked whether she had ideas, and it got Roddy’s wheels turning.

“In nursing, we’re not taught the skills to commercialize problem-solving ideas,” Roddy says. “But when you think about it, all health care is a business.”

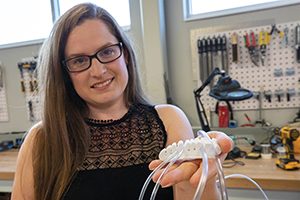

Roddy knew that nurses had no easy and reliable tool to manage the mass of cords and lines of tubing that surround a patient’s hospital bed. They are the very lifelines for medications, fluids and organ-monitoring equipment. But if one dislodged unnoticed, it could be deadly. She had her commercial idea.

With support from UWM’s Lubar Entrepreneurship Center (LEC), she’s launched a startup company. Partnering with her on RoddyMedical are UWM business school alum Katie Richter and Kyle Jansson, director of the Prototyping Center at UWM’s Innovation Campus in Wauwatosa.

Roddy’s story embodies why Lubar Entrepreneurship Center programming, dedicated to teaching innovative thinking, was created six years ago. Now, such programming has more reach than ever inside UWM’s newest building, the 24,000-square-foot Lubar Entrepreneurship Center and UWM Welcome Center.

Inside the new facility at the corner of Maryland Avenue and Kenwood Boulevard, the UWM Welcome Center hosts the Office of Undergraduate Admissions’ campus tours and visit programs. Housing this in the same facility as the LEC allows campus visitors to see students and UWM entrepreneurship programming in action.

Students work with faculty and businesspeople

At the LEC, UWM students can work on new enterprises with faculty members, businesspeople and anyone in the community. And LEC programs reach far beyond teaching students how to write a business plan or give an elevator pitch. The concepts taught aren’t limited to business-related innovation, but grounded in problem-solving skills and the ability to design anything with the user in mind.

“We believe that the skills in entrepreneurship and training in creative and innovative thinking are going to help make all our students more successful, no matter their career path,” says Brian Thompson, the LEC’s director. “Existing companies are looking for these same skills. They’re looking for employees who are innovators.”

Local philanthropists Sheldon and Marianne Lubar gave a $10 million lead gift for the new building in 2015, and the UW System has contributed $10 million to cover construction costs. Additional support has come from other alumni and donors, including the Kelben Foundation, established by Mary and Ted Kellner; Jerry Jendusa; Avi Shaked and Dr. Babs Waldman; Bud and Sue Selig; We Energies; and American Family Insurance.

Something for every student

The LEC was designed to appeal to students regardless of their academic or career aspirations. It features classroom spaces and gathering spots for speakers as well as innovation labs, where students can prototype products and software.

Programs offered include pop-up workshops, mentoring and competitions that give students the chance to win seed funding by pitting their ideas or business plans against others. Coursework can cut across disciplines, such as the “Gizmos and Gadgets” course, which is centered around making assistive devices that fit unmet needs of the disabled.

Underpinning these programs are two principles. The first involves “design thinking,” said Ilya Avdeev, the associate professor of mechanical engineering who leads program development and partnership cultivation as the LEC’s director of innovation. It’s a kind of critical thinking that improves problem-solving abilities.

“Solving problems is comparable to commercializing a product,” Avdeev said. “The design part is really important, because your product’s or solution’s design has to match the needs of the potential users.”

Taking this approach is beneficial early in the process of developing an idea, when someone is trying to figure out how to address an ambiguous problem. “You ask yourself,” Avdeev said, “‘What does a person with a particular problem want or need – and what features would make it more appealing than what’s currently available?’”

The LEC’s second foundational principle is a lean-launch methodology, an approach that leads innovators through a process of idea creation, testing and validation. Lean-launch originated at Stanford University, and Avdeev says it’s an effective way to test a hypothesis. It walks students through crafting a solution or product based on specific information provided by potential customers during interviews. Roddy went through this process, and it gave her the confidence to pursue commercializing the medical tubing organizer.

Principles apply to any field

The design-thinking and lean-launch principles provide a framework for developing ideas and finding solutions no matter the academic field, be it engineering, business or even artistic endeavors.

Daniel Burkholder, an associate professor of dance in UWM’s Peck School of the Arts, uses the principles when teaching his students. He says it helps them think through the creative parts – such as choreographing performances that have meaning and value. In a business analogy, that’s like the product.

But innovative thinking also offers a road map for building a sustainable career in a gig-centered field. By thinking of yourself as the product, too, you can better fit together piecemeal work and market yourself on a larger scale.

“We are often called upon to create our own path in terms of a career,” Burkholder said. “So you have to see opportunities, articulate your value to the public and find a way to test consumers’ approval. With the LEC’s design process, you’re able to create something and then take it out into the world with clarity and force.”

Taking the next steps

The design-thinking and lean-launch principles are important parts of a federal program called I-Corps, which is offered in Wisconsin exclusively through the LEC. Backed by the National Science Foundation, I-Corps teaches faculty and graduate students how to convert their research discoveries into products and startups.

Open to teams from six area universities, the program sends would-be entrepreneurs on a customer-discovery sojourn to hone an idea before they seek funding or spend money on a prototype. Results from the past three years include 19 local startup companies.

One of those is VasoGnosis Inc., a startup that originated while Ali Bakhshinejad was earning his doctoral degree in mechanical engineering at UWM. The software for his cloud computing-based venture provides the digital imaging techniques and analysis necessary to better diagnose brain aneurysms. With this tool, radiologists can detect aneurysms before they rupture, an often-fatal development.

Bakhshinejad used the information gleaned from his LEC I-Corps experience to modify his product concept. “In I-Corps interviews, you have potential customers tell you what they wish for,” Bakhshinejad says. “We learned that radiologists didn’t want to have to learn new software – they just wanted analyzation results directly.”

The valuable intelligence also inspired him to add a second product – a simulator for surgeons who will operate on aneurysms. The simulator allows the physicians to determine in advance which surgical approach is best for a patient.

Earlier this year, VasoGnosis was one of 50 startups to make the final round of the 2019 Wisconsin Governor’s Business Plan Contest. The contest offers links to a statewide network of community resources, expert advice and exposure that could result in additional sources of capital.

Roddy, too, turned up valuable information from her team’s I-Corps interviews. She discovered that safety concerns posed by messy medical tubing were a common worry for nurses, who spent an average of 30 minutes per shift just organizing them. She interviewed more than 100 clinical staff, and 73% reported close calls or safety events involving tangled lines, many of which endangered a patient’s life.

Jansson, one of the partners in RoddyMedical, has designed multiple prototypes – each a modification informed by feedback from nurses. “Having data makes the difference,” Roddy said.

Roddy’s team worked with the UWM Research Foundation on the patent for their device and continues to move forward on commercializing the product. Like VasoGnosis, RoddyMedical was a finalist in the 2019 Wisconsin Governor’s Business Plan Contest. Roddy’s team also earned a $25,000 grant from the Ideadvance Seed Fund that supports the entrepreneurial efforts of UW System faculty, students and alumni at campuses other than UW-Madison.

The steady progress reminds Roddy that she made the right decision to persist in the LEC’s training while building her startup. She knows the process isn’t easy, but she believes in the end, it will pay off.