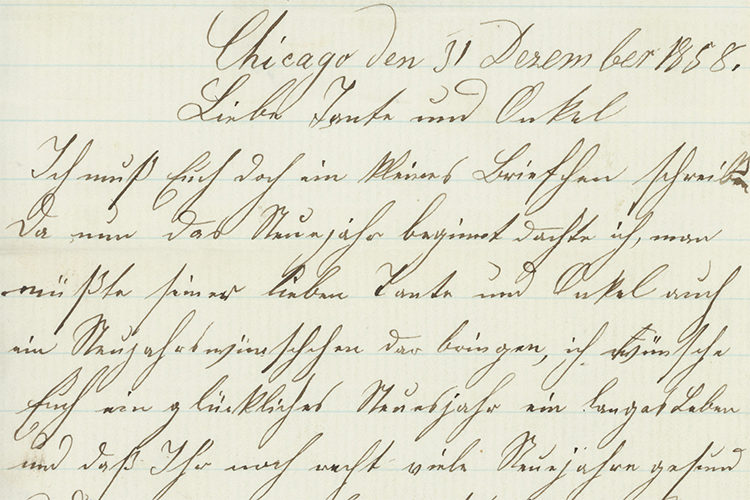

In 2005, a bit of Milwaukee history was unearthed in an old metal box. Located at Pabst Farms in Oconomowoc, the box held about 350 letters written from 1841 to 1887 by members of the Pabst and Best families, founders of what became the Pabst Brewing Company.

The letters, however, were written in a German script that is difficult to understand. Fifteen years later, two UWM students tackled that challenge and revealed what the long-lost letters say.

In spring 2020, the Pabst Mansion set up a partnership with UWM’s Translation and Interpreting Studies program to translate the letters. Over the course of an eight-week summer internship, Nastassja Myer and Marisa Irwin, graduate students in Translation and Interpreting Studies, translated and transcribed 50 pages of letters.

The letters were largely personal in nature, often written between members of the Pabst and Best families, to their friends or to their business partners from across the country.

“One of the things I’ve enjoyed about this project was that it wasn’t just transcribing and translation,” Myer said. “It was a lot of genealogy and local history. So many things had to come together to correctly read the letters. It was more than a translation project; it was a historical project as well.”

The letters are steeped in Milwaukee history. The Best family created the brewing company after emigrating from Germany. Pabst Brewing Co. started as Best & Company, then later became Phillip Best Brewing Company during the time these letters were written. Frederick Pabst, Best’s son-in-law who owned half the company’s stock, purchased half of the company’s stock after his father-in-law passed away and bought the remaining half when his brother-in-law also passed, leaving him sole owner of the company. He renamed it Pabst Brewing Co. and expanded the company.

Irwin grew up in Milwaukee surrounded by the Pabst legacy. To read the words of these Milwaukee contemporaries that she had learned about for years, she said, was eye-opening.

“You felt like you were getting a peek into their private lives,” Irwin said. “You can’t really get more authentic than that.”

Viktorija Bilic, associate professor in Translation and Interpreting Studies and a coordinator on the project, said that the letters also show readers a little about the culture of Milwaukee at that time. “They show what a German place Milwaukee was that they could speak German with almost anyone around them.”

Combining two languages

The process is not as simple as reading the original script and writing it down in English, Bilic said. “One of the challenges is reading the script, this old German handwriting. If you don’t get that right, then the translation can’t be right either.”

The letters’ authors used the German Kurrent script, which is difficult to read even for those fluent in German, Irwin said. The language is even more difficult, she said, because Germany did not have a standardized spelling system until the early 20th century.

“So even when you have the handwriting, when you’ve discovered what the word is, it may not be how it’s spelled currently,” Irwin said. “You have to ask yourself, ‘Is it an old word that you don’t know because it was written in the 1850s? Is this a misspelled word? Is this a word in a different language?’”

The writers were fluent in both German and English and would combine the two languages to create new spellings, Myer said. The word “store” might be spelled in a more German way, like “stohr,” and Milwaukee could be spelled in several different ways, such as “Milwaukie.”

“It is a mixing of two languages,” Myer said.

Solving a puzzle

Other times, Myer and Irwin understood the language but not the context surrounding the letter.

“Sometimes it can feel like solving a puzzle, because they are taken out of context. Of course, these people know what they’re talking about, and they know the people mentioned. They don’t explain around things,” Bilic said. “For us we need to decode what is going on here, do as much research as possible, and (figure out) how are the people related.”

The students and Bilic worked closely with Jocelyn Slocum, curator of collections and communications manager at Pabst Mansion. She was able to give the students valuable information on Pabst history to make sense of the letters.

“We were able to make a few more connections through these translations as well,” Slocum said. “The work they did with this is making it so that these collections can be an actual useable resource for exhibitions or researchers. To have it be widely available is huge.”

Bilic and Slocum are confident that they will be able to make more connections within the Pabst family and Milwaukee’s history as they work through the remaining letters.

A rare graduate degree experience

UWM is one of three schools in the country with a graduate program for German to English translation. This makes UWM students especially qualified to translate these letters, Bilic said.

While both Myer and Irwin noted how the internship made them feel more connected to Milwaukee, it also gave them valuable professional experience in translating, Irwin said.

“We’ve all been in internships where you’re just the coffee-delivery person,” Irwin said. “(Here) the emphasis is on actually working and developing skills that we can apply when we graduate, which I think sets UWM apart from other translation programs in the country.”

Bilic hopes to continue the internship over the next three to five years to transcribe and translate the complete collection of letters.