They are inventors, innovators and mentors. The work by more than 4,600 UWM graduate students in 104 graduate degree programs drives the academic discovery in labs all across the campus.

“They are solving problems that will improve the quality of life for all of us,” said Graduate School Dean Marija Gajdardziska-Josifovska. “And they are behind the success of UWM research, making the university one of only two in Wisconsin that is recognized by the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education – the gold standard for assessment of doctoral universities.”

From studies of minerals on Earth that can shed light on the geology Mars to deconstructing how muscles communicate with the brain, the stories below represent only a fraction of UWM graduate research enterprise, but each one is a unique slice of the journey our students take to start their careers.

Sisay Mersha, nursing

Sisay Mersha has identified a common health problem among East African immigrants: They tend to avoid seeking health care unless it’s an emergency or interfering with their daily lives. He noticed the same behavior while practicing in his native Ethiopia and is currently conducting a mixed-method study in Chicago to explore this.

A doctoral student, Mersha also is a cardiovascular nurse practitioner at University of Illinois Health.

Although the health care debate across the United States has generally centered on access to facilities and health insurance, Mersha wonders why these immigrants are so adamant about putting off health care.

“I hear a lot of patients, colleagues and friends from the community saying they have a hard time going to doctors even when they have insurance,” he said.

Mersha acknowledges that, for immigrants, access remains a huge factor because they often don’t have jobs that provide insurance. Their immigration status might be another barrier to seeking help, as is unfamiliarity with the system. And COVID-19 has exacerbated the issue of delayed care.

His research is looking at all of these factors. The answer, he says, could lie in increasing health care literacy among immigrants.

Xueling Yi, biological sciences

Bats may not be fuzzy and cute, but they make important ecological contributions, such as pollinating various kinds of crops and consuming huge amounts of crop-eating insects. And some bat populations are in decline.

Doctoral student Xueling Yi uses data science to research bats in order to improve conservation and management.

“There are more than 1,400 bat species in the world,” Yi says. “In that lineage, that group, there are so many things that we do not know.”

Among the problems to be solved: the little brown bat’s losing battle against a disease called white-nose syndrome.

Yi’s research focuses on the big brown bat, which is less susceptible to white-nose syndrome than its smaller cousin and may be growing in population. She has created genetic, genomic and environmental databases of the species.

“Using modeling approaches, you can estimate in which type of environment a bat will be found,” she says. That allows her to help wildlife managers better control the spread of disease and understand the animal’s susceptibility to climate change.

Yi’s work earned her a 2019-20 Northwestern Mutual Data Science Institute scholarship, and it could provide answers that help bats of all types, big and small.

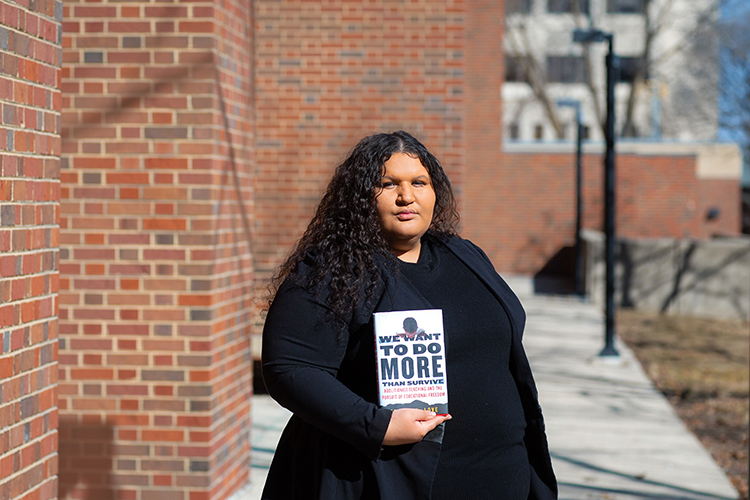

Kelly Allen, urban education

Kelly Allen’s doctoral research on how social studies teachers are being prepared to talk about race and racism in the classroom grew out of her own experiences.

Allen didn’t hear much about Black history in high school. It wasn’t until she started at UWM as a piano performance student that she discovered her passion for education after taking an Africology course.

After earning her bachelor’s degree in curriculum and instruction from UWM, she started teaching in Milwaukee Public Schools. “All my students were African American, and this was the first time they had been taught about Black history,” Allen said. “I realized this was a systemic issue.”

Her students told her they thought she should teach other teachers, and that planted a seed.

Her dissertation focuses on barriers and challenges of those preparing future teachers to address racial issues in the classroom. As part of that, she is following and interviewing 13 professors of social studies education.

“We already have a lot of research that says when people get out of school and go out into the classroom, they’re not really confident in navigating issues of race and racism,” she said. “It’s time to confront this topic head on and be explicit about what we’re doing.”

John Jurkiewicz, mathematical sciences

Doctoral student John Jurkiewicz is involved in a partnership between UWM’s Department of Mathematical Sciences and the Advocate Aurora Research Institute to help advance heart research by greatly speeding data collection methods.

The Advocate Aurora lab measures cardiac cell function, which contributes to developmental studies and ultimately benefits drug testing.

Their work involves giving the cells an electric shock and recording what happens. The scientists are most interested in the electrical signal of activity from each individual cell, called action potential, or AP. That’s because a heart cell’s AP can say quite a bit about its activity and health.

But data also is obtained from measuring the electrical signal across tissue, called field potential, or FP. And it’s difficult to separate the AP from the FP, so scientists needed to weed out those valuable signals manually.

Jurkiewicz created an algorithm that can isolate valuable experiment data in minutes, rather than hours.

“It turns out the AP versus FP classification is ‘easy’ for mathematicians to do,” said Jurkiewicz, whose paper on the work was accepted for publication in the Journal of Electrocardiology.

He intentionally made the tool accessible to other researchers. He ran the algorithm on his consumer-grade laptop rather than a supercomputer and wrote the program in the open-source language Python.

Mukta Joshi, kinesiology

Using your hands requires the coordination of many different muscles working in harmony.

“As people age or develop a disability, they find it increasingly difficult to use their hands” said doctoral student Mukta Joshi. “The hand muscles are the first to take a hit, and you use them every day in dressing, feeding yourself and even using a touch-screen tablet.”

Movement is made possible by a complicated communication system that connects your muscles to signals from the brain, spinal cord, skin receptors and other sources. Cells called motor neurons direct the electrical-signal traffic coming from all over the body to the muscles. Movement depends on the number and the firing characteristics of motor neurons. But with age, these messenger cells die off, leaving the rest to compensate by modifying the way they deliver the signal to the muscle.

In her research, Joshi measures the muscles’ signals because diminished hand task performance and muscle coordination shows up as altered signal characteristics. For example, the muscle signal of a person that has tremor while gripping will have different attributes than someone doesn’t.

She is comparing the motor neuron functioning of younger with older adults to identify exactly what changes occur as people age.

Gayantha R. L. Kodikara, geosciences

There are two theories concerning the Martian surface about 3.5 billion years ago. The first is that Mars used to be a cold, icy planet. The second contends that it had a more temperate climate, with flowing rivers and lakes.

Which is correct? The answer may lie at the bottom of a California lake.

That is where doctoral student Gayantha R. L. Kodikara is examining sediments to better understand a class of minerals called zeolites, which generally form in the presence of water.

Kodikara is comparing orbital remote sensing data, which can detect zeolites, with his findings on the ground to determine the accuracy of the data. Then, he extrapolates his findings to Mars so that scientists can better pinpoint areas where zeolites might be found.

If that happens, it will support the theory that Mars was a warmer, wet planet. It’s important because Mars’ past has implications for Earth’s future.

“If there used to be water (on Mars), why did it become a dry planet?” Kodikara said. And what, he added, does that mean for Earth?

So far, NASA rovers have not found evidence of zeolites on Mars, but Kodikara’s research shows that they may be covered, masked or otherwise unable to be detected by remote sensing data.

Stories written by Tony Rehagen, Silvia Acevedo, Kathy Quirk, Becky Lang, Laura Otto and Sarah Vickery