Technology has allowed many people to easily work from home during the pandemic. But for people with disabilities, remote working has added new challenges to the already difficult task of determining access needs at home, which can include hundreds of variables to consider.

Each situation of an individual with a disability is unique, whether a person is returning home from a hospital stay or merging their work and home environments. But tools designed to help with home assessment are not very comprehensive, said Roger O. Smith, professor in the UWM College of Health Sciences.

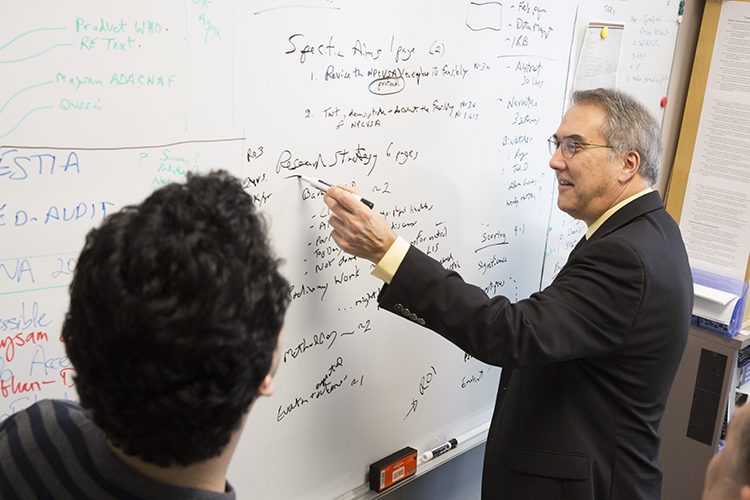

Smith and his students are working on two apps that will provide an in-depth, multifaceted assessment to identify problems in home environments. Each employ artificial intelligence that supplies missing information, compares modifications and integrates the data into a readable report.

Supported by federal grants

Smith began developing the tool, called HESTIA, in 2014 with funding from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR), part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. In the project’s initial stage, Smith’s lab established the baseline data needed to propel the apps into use.

With a new $1.5 million NIDILRR grant, Smith and UWM collaborators Jennifer Fink and Jake Luo have teamed up with Columbia University, Texas Woman’s University, Marquette University and Independence First, a Milwaukee-based nonprofit, to develop, test and add functionality to the apps.

One, called HESTIAPro, will be for use by occupational therapists. The other, called myHESTIA, will be the consumer version.

Tools currently available for home assessments gather measures of the environment and the user’s abilities, and some also include data on activities that are needed for independence, such as cooking, bathing and dressing. But they don’t account for the interactions among the three categories and they incompletely document the home environment, said Smith, who also directs the Rehabilitation Research Design & Disability (R2D2) Center, which conducts research on assistive technology and outcomes measurement.

“We designed ours from the beginning to have smarter features, such as predictive features that can propose questions based on previous answers,” he said. “There’s a level of complexity we are creating that others don’t have.”

In developing the baseline data for HESTIA, for example, the researchers incorporated more than 2,000 questions.

Added complications for working remotely

Prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, the research team are adding home-work aspects to the questions covered in the apps. This may include access to equipment that was located at the workplace or managing schedules for multiple people working in a household.

“Working remotely for a person with a disability introduces a whole other piece to assessments,” Smith said. “If you use a wheelchair, you may not be able to get up the attic office or navigate the confines of a small office space.”

Smith’s lab will work on how the users see and understand the data in the next-generation HESTIA apps. Testing with people is scheduled to begin next year. They also envision that people can use the apps on different platforms – a phone, tablet or website.

The NIDILRR awarded only four grants in 2020. Two of them are funding UWM projects – HESTIA and development of a smart robotic arm by Mohammed Rahman, associate professor in the College of Engineering.

Smith is in the process of commercializing several other apps created in the R2D2 Center.

AccessPlace offers people with disabilities reviews and accessibility ratings for various public buildings across the country. The MED-AUDIT rates home medical equipment to guide shoppers with disabilities as they sift through the thousands of medical devices on the market.