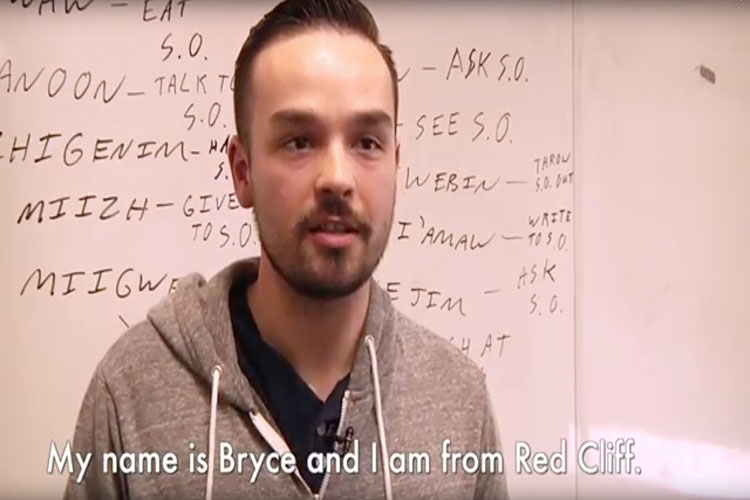

For Bryce Stevenson, studying the Anishinaabe language was an opportunity to reconnect with his heritage as a member of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

Paige Coe just thought the language – spoken by the Ojibwe, Odawa and Potawatomi tribes – was beautiful.

The ancient language that gave Milwaukee its name is echoing in the halls of UWM today. Four full-credit university courses are being offered, with second semester Anishinaabe 152 taught this term.

Offering Anishinaabe regularly is important because the language directly relates to UWM’s identity, explaining the meaning of Wisconsin, Milwaukee and other place names, said Margaret Noodin, who helps lead the classes. Besides, she added, “it is the only non-foreign language we offer at UWM. All the other languages, including English, were brought to the area by immigrants.”

Like many American Indian languages, Anishinaabe has been on the edge of extinction, counting only 8,000 to 10,000 speakers among 566 federally recognized tribes. The Native American civil rights movement spurred interest in indigenous languages, but it has been challenging to find speakers who are both fluent and have teaching ability, said Noodin, an assistant professor of English and interim director of the Electa Quinney Center.

“Many of the native speakers are over 70 years old,” Noodin said, “making this one of many world languages in danger of disappearing.”

UWM has worked to build a strong American Indian Studies program, in which Noodin teaches Anishinaabe with Michael Zimmerman, an outreach specialist in Global Inclusion and Engagement. He is a tribal liaison officer working with the American Indian Studies program and fluent in the language.

Students take the language for a variety of reasons. Some, some like Stevenson and Monea Warrington grew up on reservations and wanted to learn more about their culture.

“The Menominee tribe is a separate culture from the Anishinaabeg people, but it is the same language family,” said Warrington, who grew up on the Menominee reservation.

Other students want to learn more about the language and culture that is so much a part of the state. Some, like Colonel Rader, simply need to meet the language requirement to graduate.

“This sounded really cool,” Rader said.

Anishinaabemowin is embedded in place names common across these parts: Lake Michigan (great sea), Chicago (land of the chigag, or skunk) and Wauwatosa (firefly).

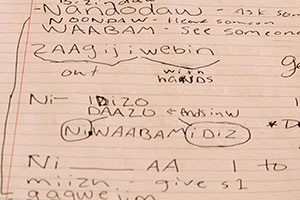

Students in the class gain insights into the tribe’s way of life through the language.

On a field trip to UWM’s Manfred Olson Planetarium, students learned Ojibwe names for constellations – and that the skies functioned as an ancient GPS. The Ojibwe word for North Star comes from the Ojibwe verb “to go home.”

The class is part of renewed efforts to preserve valuable knowledge that can be embedded in rare languages.

For example, Noodin said, the Anishinaabe word “Michigan or “michi-gaming” means a great sea, which is the word used for the interconnected system of all the Great Lakes. “Recognizing the indigenous awareness of this freshwater system shows an alternate way of studying and living with the water. Thinking of the lakes as individual political sites of industrial development — the approach used up until now — has presented challenges in maintaining the health of the water and connected ecosystems.”

Stevenson, a senior majoring in English and American Indian Studies, said neither his mother nor his grandparents spoke the language even though they lived on a reservation. Now, he is teaching his brother and other interested family members.

“It gives me a good feeling to know I can teach my family as well as teach myself,” he said.