Growing up is hard work. Just ask anyone who’s done it. Even when it looks like all fun and games, there’s serious work going on in the brains and bodies of infants, toddlers and early elementary learners.

Supporting America’s children as they grow, play and learn also is serious business for millions of adults who work as teachers, social workers and medical and mental health providers supporting children in myriad ways.

At UWM, dozens of programs and faculty members are doing this work all across campus, from the School of Education to the Helen Bader School of Social Welfare, from the Peck School of the Arts to the College of Nursing. In honor of the Week of the Young Child April 16-20, here’s a look at a few of them.

Katie Chaplin, lead teacher, UWM Children’s Center

In Clover Room at the UWM Children’s Learning Center, lead teacher Katie Chaplin teaches the babies in her care to communicate in American Sign Language. Her master’s degree from the School of Education has a focus on the inclusion of ASL with infants and toddlers. “Being a part of a child’s first milestones and supporting their early development is a privilege,” said Chaplin. “I also enjoy building relationships with families who entrust their babies to our care.”

More than 50 children are enrolled in five infant rooms at the center, which is accredited by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. A staff of 150 part-time student employees, 32 full-time professional educators and a management team provides care and education for 300 to 350 children ages six weeks to 13 years.

Fifty percent of the childcare slots are reserved for the children of current UWM students, with faculty, staff, alumni and community members filling the rest.

The center prides itself on a full-time staff that is about half UWM alumni and a family enrollment that is deeply multicultural and proudly multilingual. There are six languages spoken by families in just one infant room: Arabic, Mandarin, Shanghainese, Mon-Khmer, Spanish and English. Director Lisa Mosier says that center families and staff speak about 30 languages.

Nancy File, Kellner Professor of Early Childhood Education

Raising kids who are successful in school and in life starts with a strong foundation of language skills, social-emotional skills and parent-child relationships established at an early age. Professor Nancy File is applying this knowledge to a new study of children and families from low-income backgrounds. She is following a group of children from age 18 months to 4 years enrolled in the Next Door Foundation’s Educare program in Milwaukee, one of four cities involved in a major research project led by her colleagues at the University of North Carolina.

“We hope the findings from our research will provide new evidence to convince policymakers to increase investments in high-quality early learning for infants and toddlers,” File said.

High-quality early childhood education can have a positive impact for infants and toddlers from low-income backgrounds, minimizing some of the disparities between them and those from more affluent backgrounds.

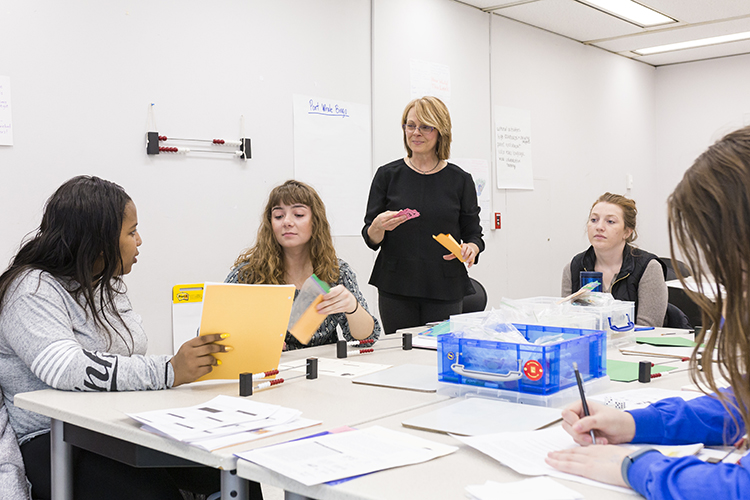

Melissa Hedges, senior lecturer and doctoral candidate

“Young kids really are natural mathematical thinkers. It’s up to us to tap into their developing math abilities and build from them,” said School of Education lecturer, doctoral student and former classroom teacher Melissa Hedges.

Hedges is teaching the next generation of math educators in the School of Education, who will someday help children from infancy to third grade build fluency with basic math facts, one of many key concepts and understandings developed in early mathematics. It’s a basic fact that 7+8=15, but it takes a skilled educator – not rote memorization – to teach children about the multiple strategies they can use to reach the right answer.

Also a consultant with the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, Hedges says that math is a strong predictor of academic success in multiple subject areas.

“That’s what makes this work critically important,” Hedges said. “In my classes, first we talk about math identity as a teacher and then how we can create a positive math identity for our students. For most people who think of math as a turnoff, it’s connected back to some really terrible experience with time testing or memorizing basic facts they had in elementary school. The idea that you are born a ‘math person’ or ‘not a math person’ is a myth.”

Bonnie Klein-Tasman, professor of clinical psychology

When kids are afraid to brush their hair each day or startle when they hear the rev of a motorcycle, the solution can be a surprisingly natural one: play, humor and silliness.

Professor Bonnie Klein-Tasman and a team of graduate-student researchers in UWM’s Child Research Neurodevelopment Lab are developing a play-based therapy to help children with a rare genetic disorder, Williams syndrome, manage significant anxieties and fears attached to common occurrences.

“Kids with Williams syndrome receive special education services for their cognitive deficits and hyperactivity symptoms,” said graduate student Brianna Yund, “but many families struggle with the impact of their phobias on daily life.”

Yund and Nathanael Schwarz, also a graduate student in clinical psychology, have a central role in researching and evaluating the new therapy and will assist Klein-Tasman and UWM alumna EJ Miecielica in developing a manual. The Williams Syndrome Association is funding the study and helped recruit children, ages 4 to 10, who began treatment at UWM this spring. The association will also help disseminate a new manual and web portal to evaluate the success of the therapy after it’s been developed.

“Very few studies have evaluated interventions for anxiety in young children with developmental disabilities,” Klein-Tasman said. “That’s why we hope our work will also inform the treatment of phobias in children with other conditions, such as autism spectrum disorders.”

Christopher Lawson, assistant professor – learning and development

Sometimes, it’s kids who make the best teachers.

“We can learn a lot from how infants respond to stimuli,” said Chris Lawson, assistant professor in UWM’s School of Education. “Infants are way smarter than most people recognize.”

Lawson is founder and lead researcher of the Cognitive Research Group at UWM, where a staff of doctoral candidates and undergraduate researchers study how children ages 3 to 8 learn. Lawson’s latest research examines generalization practices and negative evidence, and how these two kinds of thinking can build a child’s understanding of new or unfamiliar concepts.

“The central goal of education is to provide kids with specific information that you hope they use to generalize beyond one limited context,” Lawson said. “It’s the difference between teaching kids math facts, like eight times eight is 64, and teaching them mathematical concepts that they can use to build math knowledge and then multiply other numbers.”

Also learning a lot is education student Noah Wolfe, who traveled to Chicago in early April to make a presentation at the Midwest Psychological Association and will present at two more conferences before he even completes his second full semester at UWM. He’s pursuing a degree in exceptional education, and plans to eventually earn an advanced degree in psychology.

“I think that being a future teacher and working with children, you have a really important role in shaping the next generation of advocates and learners and leaders,” Wolfe said.

Joshua Mersky, associate professor of social work

Joshua Mersky is at the forefront of translational research – the process of using scientific evidence to develop real-world solutions to social problems – to help more Wisconsin kids grow up healthy, happy and strong.

Mersky evaluates a statewide network of home visiting programs that connect low-income parents to services and resources they need to raise children who are healthy and ready to learn. He’s also co-director of the Institute for Child & Family Well-Being, a partnership between Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin and the Helen Bader School of Social Welfare.

Practically speaking, he says: “There is no shortage of effective interventions that promote resilience. But we need to find ways to make sure that those strategies reach populations who stand to benefit the most.”

He particularly enjoys working directly with community partners such as the Next Door Foundation to improve outcomes for vulnerable children and families.

Lynn Sedivy, lecturer, School of Education

“Coming to the United States from a refugee camp can be a terrifying and overwhelming experience,” says Lynn Sedivy, a former English as a second language (ESL) educator who now teaches early-childhood education and ESL to aspiring teachers at UWM.

In the community, she works with children who are refugees, helping them create books about their first experiences in American schools. The children gathered photos of items and rooms in their schools and wrote captions in English for books titled “My New School.”

With the influx of newcomers into schools slowing down, Sedivy is working with Milwaukee Public Schools to provide bilingual books in a variety of languages to school classrooms and libraries, and also working on other plans to help children who are refugees feel welcomed. The projects, funded through a children’s literature grant and the School of Education, support children who speak Burmese, Arabic, Karen, Malay, Swahili, Somali and Haitian Creole.

Writing “My New School” gives the children a fun way to overcome their fears and learn more about their new environment, Sedivy said. And putting bilingual books in the classrooms gives teachers extra resources. “I really want to validate these children’s first languages,” she said.

Anna Wieker, lead teacher, UWM Children’s Center

Two years ago, Anna Wieker was one of about 140 student employees at the UWM Children’s Learning Center. Today, she’s a UWM alumna and full-time lead teacher in the center’s Ivy Room, where she leads a classroom of children from 10 to 20 months of age.

“My initial focus at UWM was secondary special education, but after working at the center and doing an internship, I decided that early childhood is where I wanted to be,” Wieker said. “Being a student staff here was an amazing experience. This place becomes your home away from home.”

Now that she’s professional staff, Wieker has learned words in American Sign Language, as well as the home languages of families, nurtured young children through developmental milestones and become an experienced mentor of student staff. She has learned how to collaborate with families to provide the best quality experiences in that child’s life, at home and at the center.

The best thing about her job? “Seeing the rapid growth of these young children and watching them find joy in the simplest things. I come to work every day and have little people running over to greet me. I get to know each of them as individuals.”

Silke Schmidt contributed to this report.