A bright swirl of color reminiscent of a crystalized ammonite shell is the focal point of the UWM Arts Center’s main stage. Everything in the room curves around it— the purple seats, the black walkways, even the cast-off backpacks of students.

The space was made for movement, for noise, for theater, yet a hushed stillness fills the room. Irish accents waft through the curtains, as if ghosts were acting on the stage.

Behind those curtains are actors, rehearsing for a pandemic-driven reimagined staging of John Millington Synge’s “Playboy of the Western World.” The Peck School of the Arts production will be performed without a live audience due to COVID-19 restrictions, relying on technology to immerse viewers in the performance that will be available for streaming on April 28.

Making adjustments

Jim Tasse, the director and UWM senior acting lecturer, and other instructors at Peck had to shift directions and adapt five different productions in accordance with health guidelines for UWM’s Theatre Fest ’21.

The shows featured in Theatre Fest ’21 have been adjusted in different ways: Some will be performed in front of small audiences, others will be recorded and edited for streaming.

Tasse’s interpretation of Synge’s play will be the only Theatre Fest show performed in an entirely audio format.

The actors’ vocal performances are compiled by a production team that will add original sound effects to create what Tasse calls a “radio play.”

“When we use the term radio, we’re not talking about 96.5 WKLH,” said Chris Guse, the sound designer and UWM Sound and Scenic Production associate professor. “We’re talking about what radio was in the ’30s and ’40s as much more of a human experience. The intimacy of that, the closeness of the action, makes it feel very personal.”

Rehearsing remotely

“Playboy of the Western World” was slated for production in 2020 before the pandemic hit and halted live performances. Tasse needed to rework the play to accommodate virtual rehearsals and actors being scattered across various remote locations because of lockdown.

The physical connections of facial expressions and body language got lost through the screen, Tasse said, which makes it hard for the actors to play off each other.

“My thought was, ‘OK, it’s a play of language, so let’s focus on that,’” Tasse said. “We talked about (how to adapt the play) as faculty and that perhaps we could find a way to make, for want of a better description, a radio play.”

Synge, an Irish playwright, wrote all the dialogue in an Irish dialect influenced by the syntax and vocabulary of Gaelic, which made the piece technically challenging to perform.

“There’s a very kind of specific task for an actor to be able to engage with the dialect, so we were able to concentrate on that, so that kind of work works pretty well on video with a good set of headphones,” Tasse said. “Synge wrote for people (the Irish) who had been colonized by the English. That ends up being this really wonderful, robust and seemingly simple but actually very complex language.”

More difficult to connect

The initial rehearsals when students first learned their lines and mastered their Irish accents were held virtually over video calls.

“You certainly don’t want to have a screen in between the actors as their performance,” Guse said. “That’s one of the big problems that the acting folks face — it’s all about empathy and the human condition.”

Guse taught students how to record themselves and create sound effects over video calls and pre-recorded lectures. The transition to a virtual classroom space went smoothly, Guse said, because he already had a background in online instruction.

Some acting students attended class, which doubled as rehearsal, hunched under a blanket or from their closet to block out sound, Tasse said.

Researching sound effects

Production students researched old sound effects and analyzed the play to identify ways to enhance the storytelling during the weeks leading up to the play. Most of their work, which was all done remotely, happened after recording the play, according to Guse.

The actors met their costars in person for the first time when they entered the main stage in the Arts Center to record their audio. They had three days— March 15, 16 and 18 — to record the three acts of the play.

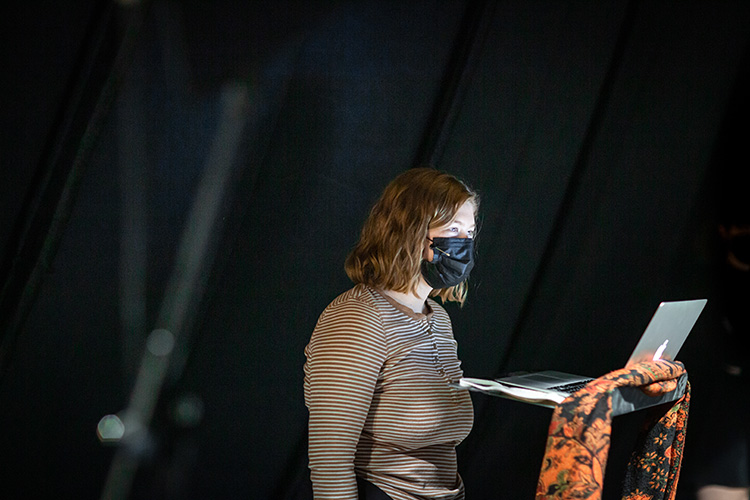

To avoid recording background noise, the actors recorded their performances in shifts, depending on the scene, huddled in the shadows behind the heavy purple curtains arranged in a skinny oval. Scripts were propped up on music stands or held, and microphones were clipped to their clothes.

“We’re relying solely on the voices to tell the story,” Zoe Osk said, seated in the back of the auditorium while waiting her turn to record. Her character, Susan Brady, doesn’t appear until the second act.

A good focus

Osk, a senior, transferred to UWM in Spring 2020, roughly a month before the pandemic shut down most in-person classes and moved instruction online. However, the past academic year has been a good experience for her.

When asked if she liked the focus on voice acting, Osk said, “Honestly, what we’re working on right now should be applied to every show. Normally we don’t get a lot of time to do that, so it’s been really cool.”

The full radio play of “Playboy of the Western World” in the form of a 3-file audio playlist will be posted online on April 28 for free with no end date.