Summer brings warm weather, sunshine and time to enjoy Wisconsin’s beautiful waters.

Unfortunately, it can also bring potentially toxic blue green algae resulting from the combination of sunshine and chemicals like phosphorus and nitrogen running into the water from farms and roadways. These conditions create algal blooms that can result in toxins harmful to humans and pets.

UWM researchers are studying these algae to better understand how and why they form and look at ways to monitor and predict the growth of the toxic forms.

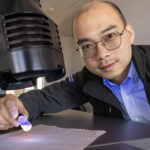

Todd Miller, an associate professor of environmental health sciences in the Zilber School of Public Health and director of the Laboratory for Aquatic Environmental Microbiology and Chemistry, is one of those researchers studying the toxic blue green algae. These algae are often found in inland waters, but are now appearing in areas of the Great Lakes, Miller said.

Ryan Newton, an assistant professor in the School of Freshwater Sciences, is looking at the blue green algae on the genetic level to determine how these organisms grow and reproduce and what factors cause increased toxin production.

Can produce toxins

While algae occur normally in Wisconsin’s waters, and many are not toxic, the blue green algae produce toxins such as microcystins, which can make people sick, Miller said. Swallowing the water can cause flu-like symptoms, rashes or respiratory distress.

These harmful algal blooms also can affect drinking water quality and recreational uses of lakes and other water bodies. In Milwaukee, for example, several years ago a number of events at the Juneau Park Lagoon had to be canceled because of algal blooms.

Climate change is a factor in the increased dangers from toxic blue green algal blooms, according to Miller, as higher water temperatures combine with more frequent storms and runoff to produce wider-spread blooms.

“We’re concerned about climate change and the impact it’s having on waters that don’t have algal blooms now,” Miller said. “Green Bay and Lake Winnebago have had this issue for a long time, but we’re seeing more lakes that never had this problem, including near shore waters of Lake Superior.”

These algal blooms can also affect drinking water in areas that rely on the lake for their water supplies. This happened in Toledo in August 2014. Half a million people were warned not to drink their water, cook with it or brush their teeth because of toxins as a result of a harmful algal bloom growing in Lake Erie.

Studying and educating

Studying and monitoring the blooms is part of the answer to controlling them. UWM researchers were involved in a five-year study of the algal blooms in Green Bay that looked at what toxins were there, what algae were making the toxins and under what conditions.

Educating the public and state and local policymakers is another critical part of the solution. Researchers and others have been working with farmers, the EPA and policymakers to find ways to limit the runoff of phosphorus and nitrogen that eventually flow into Green Bay.

Another technique is plantings or bioswales around inland water bodies like Milwaukee’s Juneau Park Lagoon that are near roads. These bioswales can filter some of the runoff before it gets into the water.

Staying ahead of the algal blooms is also important.

Miller and his research team have been using buoys with sensors to improve monitoring. These UWM buoys are deployed in Green Bay, Sturgeon Bay, Lake Superior (around the Apostle Islands) and in Lake Michigan at Bradford Beach and the Summerfest Lagoon. These buoys can help pinpoint conditions where and when the algal blooms may form.

“In studying large bodies of water like Lake Michigan, we’ve found that algal blooms can vary from one side of the Lake to the other,” said Miller.

Better ways to share data

The research team is also developing better and faster ways to gather and share the data the buoys collect in real time with researchers, policymakers and the general public. The data goes to a website hosted by UWM that is open to the public.

In addition to monitoring for blue green algae, buoys collect information on water temperature, wind, light and other water quality issues such as harmful bacterial contamination.

Harmful algae not only affect water quality but also can get into the food chain. Miller and his team recently published a study of dietary supplements and beverages that contain algae. They found that some of these products contain very high concentrations of toxins. “Algae is one of those things being promoted as healthy, but no one controls whether they’re contaminated with toxins, Miller said.

Some cities, like Toledo, are doing a good job at controlling algae in the drinking water, he added, but it comes as increased expense and not all municipalities test for it.

With the increasing number of areas having problems with algal blooms, more research and monitoring are critical, Miller said. Ultimately, climate change also needs to be addressed.

“There are more lakes that never had this problem, but now are having it. How to control climate change is another whole issue. We need to rely on political change and changes to personal behavior.”