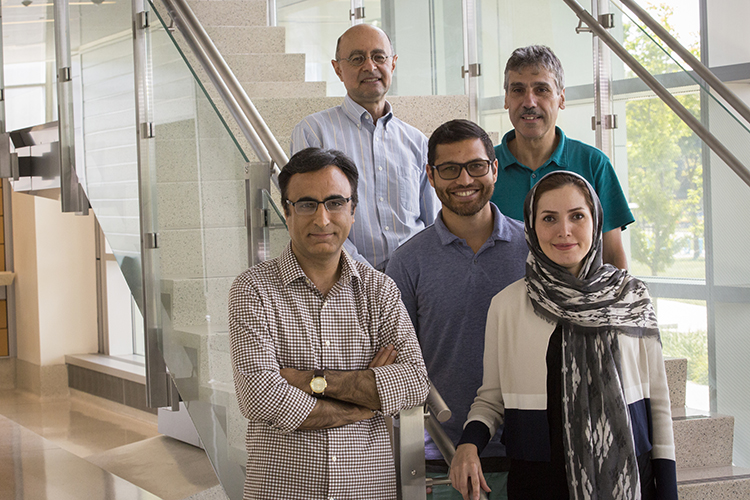

A research collaboration led by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee has for the first time created a three-dimensional movie showing a virus preparing to infect a healthy cell.

The research has the potential to fundamentally advance our understanding of how biological processes inside the cell work. That could lead to better treatment for the horde of human diseases caused by viruses.

The feat was made possible by UWM physicists, who developed a new generation of powerful algorithms to reconstruct sequential images from an ocean of unsorted, noisy data.

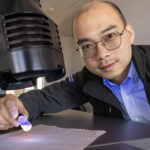

Using the brightest and quickest imaging equipment available — an X-ray Free Electron Laser (XFEL) at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California — an international team of researchers collected millions of individual “snapshots” of a virus in unknown orientations and states.

“In the past, scientists have tried to infer what’s happening in a molecular-scale biological process by looking at a still photo at the start and a still photo at the end of a process,” said Abbas Ourmazd, UWM distinguished professor. “But you then don’t know what happens in between. With this method, we are in a position to watch biological machines perform their functions.”

By combining concepts from machine learning, differential geometry, graph theory and diffraction physics, the researchers created an algorithm able to reconstruct sequential images.

The work, done in collaboration with Professor Brenda Hogue, a virologist at Arizona State University, and Andrew Aquila and his colleagues at the Linac Coherent Light Source at SLAC, is published today in the journal Nature Methods.

In order to replicate, a virus invades a heathy cell, releases its DNA and effectively hijacks the cell’s machinery to fabricate copies of itself. The multitude of viral progeny is then expelled.

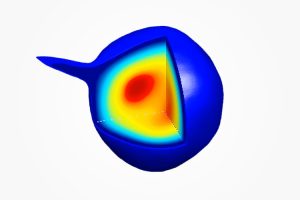

The researchers’ results show the virus re-arranging its genomic content and forming a tubular structure to empty its DNA into a cell.

“This work provides a new approach to understanding the changes that viruses undergo during infection,” said Hogue.

In addition to showing how these events unfold, the UWM researchers discovered that the reorganization of the virus’s genome and the formation of a tubular structure are not independent events, but part of a concerted simultaneous process.

Too small to photograph

Most viruses are too small to be photographed by light. The XFEL’s intense X-ray flashes produce “snapshots” of particles at the nanoscale through diffraction: The X-rays hit the particle and scatter in a pattern that provides the data for mathematical reconstruction.

More than five years ago, UWM senior researcher Ahmad Hosseinizadeh, the first author on the paper, began working on the algorithm needed to turn noisy XFEL snapshots into still 3D images. From there, progress was made by collaborative work with scientists from different backgrounds, said Peter Schwander, a UWM associate professor. “People didn’t think it could be done,” said Schwander.

“We’ve been developing algorithms to reconstruct images in the correct order since 2009, so the UWM team was well-positioned to perform such an analysis,” he said. “But it was difficult. We were able to make it work by watching how the experiments are done and adapting the data science to the data.”

Other UWM researchers who are co-authors on the paper include Jeremy Copperman, Ghoncheh Mashayekhi, Russell Fung, Ali Dashti, Reyhaneh Sepehr and Professor Marius Schmidt.

This work was done as part of UWM and ASU involvement in the BioXFEL Science and Technology Center, which is funded by the National Science Foundation. Its mission is to use the XFEL to watch biomolecular machines at work, understand how they support life, and provide training and new tools to the scientific community.