The tsunami of plastic waste flooding into oceans and the Great Lakes eventually breaks down into bits that are about the size of a sesame seed in a process called weathering.

These microplastic particles often come from sources that you wouldn’t expect: They are shed from washing clothes made from synthetic fabric, from tires as they wear, even from the discarded single-use face masks used during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite the prevalence of microplastics, little is known about how they behave as they transport chemicals and degrade in aquatic environments, said Laodong Guo, a UWM professor of freshwater sciences. Do they degrade completely into dissolved molecules that no longer have the structure of plastics? Or do they deteriorate into even smaller, invisible nano-sized particles that retain the chemical structure of a plastic?

If they dissolve completely, they simply become natural organic matter. Nanoplastics, on the other hand, raise concerns about ecosystem and human health, Guo said.

Possible harm to people

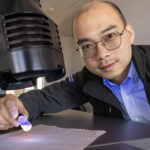

The National Science Foundation recently awarded Guo $360,800 to investigate how microplastics behave in water and the chemical properties of their smallest particles during weathering.

Studies have shown that microplastics pass right through fish, which ingest and then excrete them. But nanoplastics may be another matter.

“Microplastics become more toxic or dangerous when they reach nanoscale because, at that size, they can freely get into the body when ingested and become part of the fish tissue,” Guo said. “Then, when people eat the fish, those nanoparticles accumulate in our bodies.”

Though the health effects of nanoplastics on humans are not known, studies in animals have shown that nanoplastics change the gut microbiome, affecting their immune and nervous systems.

Degradation pathways

Once microplastics degrade to nanoscale, they are difficult to detect and isolate. So Guo will track changes using special equipment that identifies chemical properties and characteristics, such as the size of the particles and molecules, contained in samples from laboratory experiments.

“I’m trying to understand the degradation pathways of microplastics during photochemical weathering, which is driven by ultraviolet light,” he said. “We want to see which process or mechanism is the predominant one, how quickly it happens, and what the degradation products are.”

Guo’s lab already has found that pristine microplastics and plastic microfibers release water-soluble organic matter into the environment to a varying extent. They also break down differently and undergo chemical changes in multiple ways.

Another concern is that microplastics contain toxic additives that can be released into water during weathering. Guo’s project may also shed light on the role microplastics play in transporting and distributing these chemical pollutants.