Graduate students are the workhorses of university research. Their investment in scholarly inquiry will become the foundation of their academic and professional careers. Just as important, said Graduate School dean Marija Gajdardziska, is that research solves problems that we all face.

Increasingly, these researchers are being asked to explain their work to general audiences in a way that’s compelling – and brief. With constraints on funding, this skill is more important than ever. It’s one reason the Graduate School hosted UWM’s inaugural Three-Minute Thesis Competition (3MT), in which grad students practice their “elevator pitch” techniques.

The students below represent a very small sample of the range of research being conducted across campus. The top three winners in the 3MT are included, along with others.

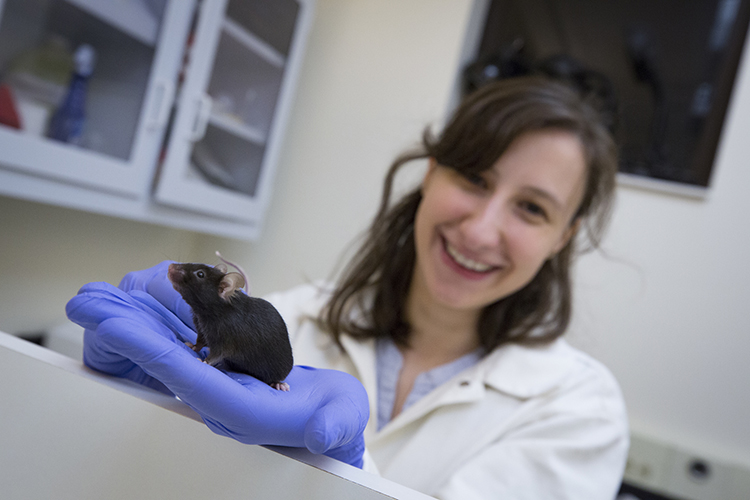

Lisa Taxier, experimental psychology

An estimated 5.7 million Americans have Alzheimer’s disease, and nearly two-thirds of them are women. One contributing factor is that estrogen hormones protect memory, so the loss of them at menopause puts women at greater risk.

But it’s not that simple. Taxier studies the interactions among a person’s brain, genes, hormones and sex to untangle the conditions that either lead to memory loss or protect against it.

It’s turning out to be quite a daunting puzzle because both hormones and genes are involved in memory – but they also accomplish many other tasks in the body.

Taxier’s research, funded by the Alzheimer’s Association, shows that, like hormones, the effects of different variants of a gene called APOE are not the same in men as in women.

Taxier, who took first place in the UWM Three-Minute Thesis competition, has found that one gene variant of APOE is memory protective in male mice, but not in female mice.For females with a different genotype, APOE4, estrogen replacement therapy during early menopause increases the risk of memory loss – the opposite of what occurs in women without that variant who take estrogen.

Jeremiah Huth, architecture

An avid cyclist who has pedaled many miles outside the city, Huth has observed one outcome of economic recovery on the landscape: Private development that was halted during the housing bust of the mid-2000s is now ramping up, threatening rural spaces once used for public recreation.

Referred to as “ghost parcels,” these spaces hold potential to enhance the built environment and also serve as recreational buffers between towns and cities, and maybe even provide opportunities for sustainable farming – if the zoning and mixed residential plots are designed for it.

Huth’s research focuses on two such parcels in Ozaukee County, one where a citizens group is working with a developer to design a subdivision that would leave a lakeside segment of the property in its natural state.

In addition to subdivisions, many of these areas are used for one-crop, large-scale farming. So Huth also has incorporated segments that could be reserved for more sustainable farming practices.

“The idea is to get people thinking about alternatives to the way we develop and occupy these rural spaces,” said Huth. “The Ghost Parcels project could be the seed needed for investment.”

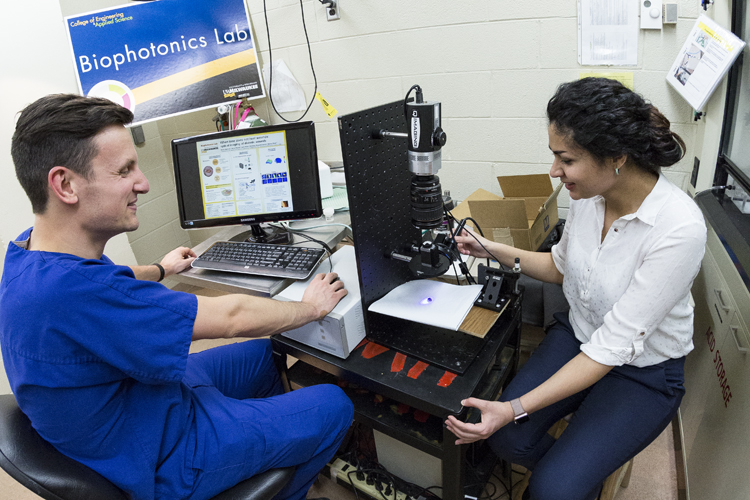

Shima Mehrvar, electrical engineering

Millions of diabetics in the U.S. struggle with wounds that never heal because the disease hinders proper cell function.

To find a solution, Shima Mehrvar, a graduate student in electrical engineering, is helping nursing senior Kevin Rymut investigate a treatment with near infrared (NIR) light that appears to improve healing of these stubborn wounds.

Mehrvar has created a novel optical system that reveals molecular indicators of damage in live tissue. It resolves Rymut’s main obstacle: How can you study something you can’t see?

Light is used in two ways: In Mehrvar’s device, biomarkers for cell damage glow when they absorb light with specific wavelengths, revealing the location and extent of cell injury within the wound.

The wound is also exposed to certain regiments of NIR light, which gradually tones down the inflammation that is a tell-tale sign of cell damage, while the imaging apparatus tracks the progress and shows the status of both the structure and the cellular function simultaneously.

The two researchers hope to quantify the right dosage and duration needed to use NIR light as a treatment for chronic wounds.

Jessica Skinner, anthropology

UWM’s Archaeological Research Laboratory is the curator for skeletal remains of individuals recovered from the Milwaukee County Poor Farm Cemetery, the site of nameless graves of residents between 1882 and 1925.

Anthropologists like Skinner use digital scans to examine the remains for clues to the life experiences of the poor, institutionalized and unclaimed of the late 19thand early 20thcenturies.

The human skeleton contains a record of life events, such as injury, infection and personal habits. For example, reactive bone growth around a poorly healed fracture often indicates that the person continued to use that limb despite the fracture.

Anthropologists try to link these “signatures” with personal characteristics that may have been recorded in historical documents.

For Skinner, the remains of these individuals not only inform the past, but may offer new ideas for medical treatment today.

Her work accomplishes something else too. “We can now return the personhood of the dead and allow them to speak to the human community,” she said.

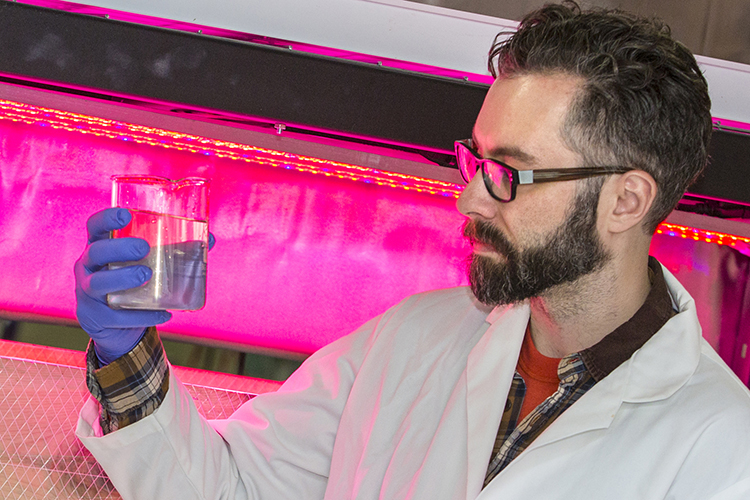

Ryan Bartelme, freshwater sciences

Aquaponics – raising plants and fish together – is so fascinating to microbiologist Ryan Bartelme he decided to go to graduate school to make his contribution.

One challenge in aquaponics is perfecting the nitrogen cycle, something that Bartelme believes can be done naturally by understanding and manipulating the microbial communities in the water.

For example, he said, certain microbes can convert toxic ammonia from fish waste into nitrate, which is beneficial for leafy plant production and relatively benign to fish. Harnessing these micro-organisms could improve the current method of mechanical filtration.

Another common problem is that the plants in aquaponic systems need supplemental iron, adding to the cost. But Bartelme believes introducing microbes into the system could improve the absorption of iron.

“If we knew more about the micro-community, we could manage the nutrients much better,” he said. That’s why he is working with the Great Lakes Genomics Center at UWM’s School of Freshwater Sciences to investigate four microorganisms that each accomplish different tasks in waste remediation.

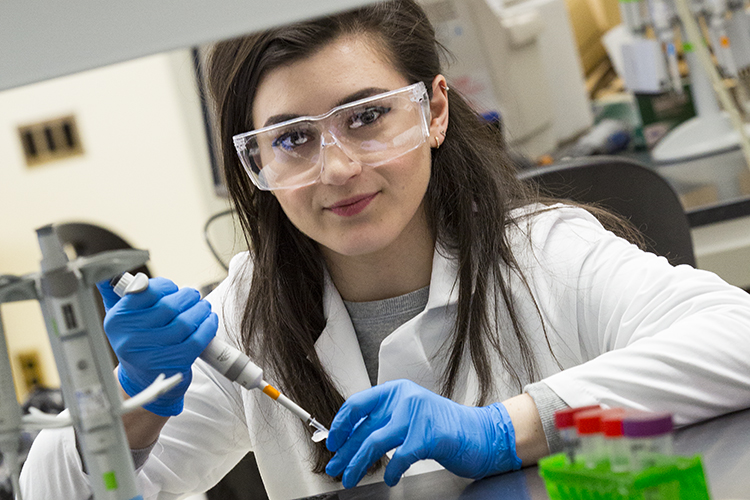

Anahit Campbell, chemistry

One in every 1,500 babies are born with an obstruction that blocks the flow of urine from a kidney to the bladder.

It usually affects only one kidney, but the methods of diagnosing this ailment are invasive. As a result, the condition, called obstructive uropathy, often goes undetected.

Chemistry graduate student Anahit Campbell described three current detection methods when she presented at the UWM Three-Minute Thesis competition. “If I were a parent, which option would I choose for my child? The answer is none of them,” she told the audience.

Instead Campbell is helping to create a noninvasive diagnostic tool that is also quick and inexpensive. The tool will expose a sample of the baby’s urine to aptamers, similar to antibodies,that naturally interact with the proteins that are biomarkers for the disease if they are present. It is similar to the way a pregnancy test works.

It’s an easier and less stressful way for new parents to get an earlier diagnosis, opening up more treatment options earlier – and that can save lives.