Phone and laptop chargers? Check. A two-week supply of clothes? Check. Tissues and cough drops? Check and check.

These are items that UWM recommends students pack in their “go bag,” in case students who live in university housing need to enter quarantine or isolation quickly.

If students in residence halls come into contact with someone who is COVID-19-positive or test positive themselves, they can isolate at home. But for some students, this is not an option, said Carol Klingbeil, Doctor of Nursing Practice program director and clinical associate professor in the College of Nursing. In that case, the university moves them to a residence hall room where they can isolate or quarantine safely, Klingbeil said.

But what if the student forgot to pack their medication or simply wants someone to talk to?

This is how Kim Litwack, dean of the College of Nursing, thought to pair students in on-campus isolation or quarantine with graduate nurse practitioner students for a one-on-one phone call.

“It was the mom in me,” she said. “I think we owe parents – and the students – the responsibility of touching base. I want to make sure the students are OK. We have an obligation to check in.”

A voluntary program

Through this system of student welfare checks, a graduate nurse practitioner student is paired up with students in isolation. The nursing students ask questions about the students’ physical and mental health, their academic well-being and their needs.

The student nurses also offer campus resources to help get through isolation, including University Counseling Services; YOU@UWM, an online platform that allows students to set goals and access additional mental health resources; and SilverCloud, which provides self-guided programs for mental health.

“It is just finding out if there are unanswered questions or worries and what we can offer them so they’re not just sitting there trying to figure it out,” Klingbeil said. “There’s always questions.”

If students forget something crucial in their room – like medication – the nursing student can help. If the student has not made alternative arrangements for in-class lectures or makeup work, nursing students are there to remind them. And after the initial call, if the student doesn’t want to continue with the program, the nursing student will take them off their list, Klingbeil said.

“It is all confidential, and it is voluntary for students. It’s really an initial check and then ongoing if the student thinks it’s going to be useful,” she said.

A win for both parties

These student welfare checks don’t benefit only the students in isolation or quarantine. The calls to students in quarantine count toward clinical hours for nursing students. These are necessary for nursing students to finish their degree and attain their license.

When campus shut down last spring due to coronavirus, many nursing students were not able to fulfill their clinical hours. This program allows students to make up missed hours. It’s a win-win, Litwack said.

“(Nursing students) know how to ask the questions. They know the campus resources, and it meets their needs, but it also meets the needs of the students” in isolation or quarantine, she said.

Young adult health easily overlooked

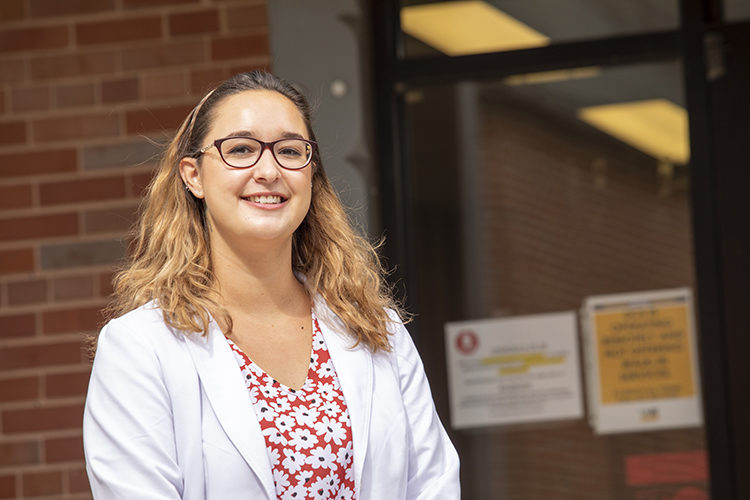

Sarah Sarandos is one of the graduate nursing students conducting welfare checks. She said young adult health is easily overlooked.

“People will think, ‘You’re 18 to 25 years old. You’re the healthiest portion of the population right now, so you don’t need as much attention.’ In some cases that may be true, but there are still lots of age-specific factors that affect this age group,” she said.

This is especially important with young people with COVID-19, she added. Even though young people are thought to be the least at-risk, Sarandos notes that this is not the case for every young adult. “They need help too.”

Most students she talks to, Sarandos said, seem fine. They talk with family, stay in contact with professors and monitor their symptoms. But Sarandos still makes a point of letting students know who they can call if they need help.

“Even if they say they’re OK, a lot of the times they will take the resources. They don’t know how they’ll feel in the next 10 to 14 days.”

Sarandos said calls can last anywhere from five to 15 minutes or more.

“Some need fewer resources, and some don’t even want to talk. But there’s always outliers,” she said. “They just want someone to talk to.”