The earliest complex animals were soft-bodied creatures without bones, which explains why they have left a scant fossil record. The next best thing to validate their existence? Find fossil evidence of their behavior, such as trackways and burrowing.

That’s what a group of scientists, including UWM’s Stephen Dornbos, recently uncovered in ancient marine rocks of western Mongolia.

The organism capable of this complex burrow construction was previously thought to live later in time – in the Cambrian Period of the Earth’s geologic time scale.

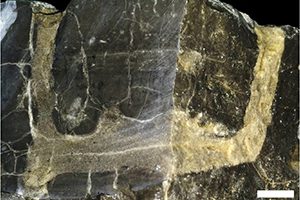

Dated at between 555 million and 541 million years ago, the preserved burrows they found could have been made only by a complex animal, meaning one with a distinct front and back, and three tissue layers. The fossils show U-shaped vertical tunneling, penetrating at least 4 centimeters into the sediment.

The behavior is indicative of a complex animal – likely a worm-like creature – building a semi-permanent home in the sediment, said Dornbos, chair and associate professor of geosciences at UWM. They likely filtered suspended organic material from seawater for food.

Scientists are keen to find out more about these animals because they bridge the gap between simple organisms, such as sponges and jellyfish, and the diversity of higher animal forms that began to appear after the start of the Cambrian at around 541 million years ago.

While they aren’t the earliest trace fossils found, Dornbos said, they provide further evidence that the evolution of animal complexity predated the “Cambrian explosion,” when a sudden burst of diverse kinds of animals with skeletons appeared in the fossil record.

Dornbos is second author on the paper describing the find that appeared in the journal Royal Society Open Science Feb. 28. The team also included first author Tatsuo Oji, a professor at Nogoya Univerity, with Keigo Yada, Hitoshi Hasegawa, Sersmaa Gonchigdorj, Takafumi Mochizuki, Hideko Takayanagi and Yasufumi Iryu.