In Kenya, a country where one in four people lacks access to electricity, charcoal is a staple fuel source. It’s light, small, easy to store, burns longer and hotter than wood, and is nearly smokeless.

It’s also speeding up the country’s deforestation.

“So, (we wanted) to see if there was a difference in charcoal yield from different species of trees that they were growing in the area,” said Jacob Rankin. “We were trying to determine if there was a significant difference in yield – if Kenyans can make charcoal more efficiently with a particular tree versus another.”

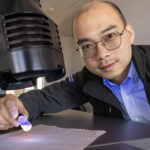

Rankin and his research partner, Emily Ruder, graduated from UWM this spring with majors in conservation and environmental science. Last summer, though, the pair spent two months in Kenya experimenting with charcoal production techniques at the Drylands Natural Resource Centre, a nongovernmental organization in Mbumbuni, Kenya, that promotes sustainability practices in agriculture and land management.

“Hopefully our research provides them with some more knowledge of their local resources to improve the way they do things – more sustainably,” Rankin said.

Baking a briquette

Most Americans thinking about charcoal will envision a Kingsford bag next to a Weber grill.

“In Kenya, it’s a little bit more rugged,” Ruder said. “To make charcoal, you need an organic material, and you need to cut it off from any access to oxygen, and then put it under super-high heat. You can make charcoal out of any kind of organic material, as long as it’s thick enough.”

Traditionally, Kenyans and other cultures around the world have made charcoal using earth mounds – piles of dirt where they bury branches and logs to prevent exposure to oxygen. Then, they light a fire beneath the mound and wait for the high heat to carbonize the buried wood.

“The problem with that way of production is that it contributes to forest degradation. The forest resource is now of lower quality. It also has really low conversion rates of wood to charcoal,” Rankin said.

The Drylands Natural Resource Centre improved the process by teaching farmers to create charcoal in steel drums, which are more airtight than earth mounds. But Ruder and Rankin were more interested in the raw material. Do different types of wood make for better charcoal? Does it matter how dry the wood is beforehand?

Building a better briquette

Rankin and Ruder tested seven types of wood and experimented with different lengths of drying time. Their results were encouraging: They found it’s not so much the type of wood that affects charcoal efficiency, but the part of the tree.

“You have the bark that was around the wood and then the actual, good hardwood inside the bark. When you carbonize that, you can literally peel the bark off of the wood and then you’re left with two types (of charcoal): One is the briquette, or non-premium kind of charcoal, which is from that bark, and then the other piece you have left is the premium charcoal,” Ruder said.

The charcoal made from bark is lower quality, burning for less time at lower temperatures and producing more smoke than charcoal from hardwood. With that in mind, Rankin and Ruder were able to make some recommendations.

“For example, Terminalia brownii is a very dense wood. The premium charcoal that is yielded from it is really high quality. But it also has a lot of bark surrounding it, so it also makes a lot of non-premium charcoal,” Rankin explained. “Whereas with a species such as Senna spectabilis, it yields a lot of premium charcoal, but the bark is minimal.”

“We also found that there was a significant difference between drying the wood for two months versus drying it for three months,” Ruder added. “If you’re drying the wood between one and two months, it’s not going to make a difference. But drying it for three months will make that extra difference, so that’s what we recommended. It dries it out more, and once it’s drier, it produces a better yield of charcoal.”

And, she noted, better yields of charcoal will lead to less deforestation.

Next steps

Rankin and Ruder presented their research at the virtual UWM Undergraduate Research Symposium in April, where they were awarded an outstanding presentation ribbon for their work.

“We’re hoping that this research can help the DNRC in their charcoal production and create a model and an example for other small-scale production,” Rankin said. “This is knowledge that they can share in their workshops, not only within their village, but maybe around Kenya and the region in general.”