Greetings, BugFans,

Another day, another Orthopteran. This revised episode from 4 ½ years ago celebrates some of the other insect noisemakers. Alert, veteran BugFans will note some new pictures, too.

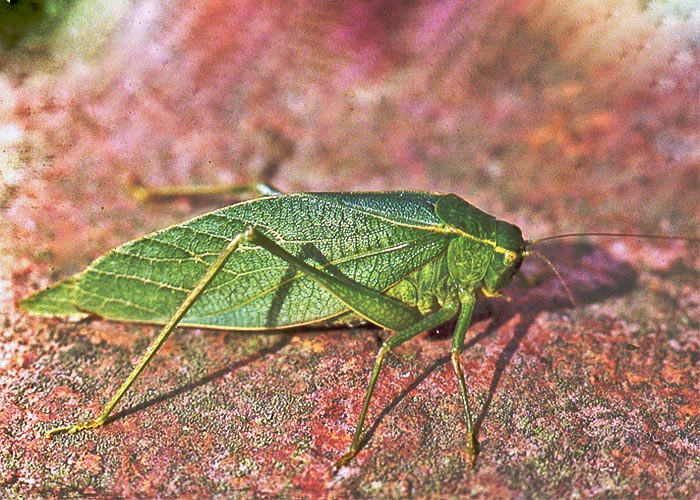

Katydids are classified in the order Orthoptera (“straight wings”) and in the family Tettigoniidae, the Long-horned (long-antennaed) Grasshoppers and Katydids. In order to belong to this club, your antennae have to be as long as or longer than your body. These are large, beautiful, leaf-textured, green (usually) insects of grasslands, open woods and edges whose often ventriloquistic calls can be heard both day and night.

The Katydid Family album includes a chunky “True” katydid (genus Pterophylla), and some leaner “False” katydids (to distinguish them from the “True,” but they are katydids, all) that the BugLady suspects are in the genera Neoconocephalus (the coneheaded), Microcentrum (the angular-winged), Amblycorypha (the round-headed), and Scudderia (the bush katydids). She is not going to climb any farther out on the taxonomic limb than that; male bush katydids are hard to tell apart, and the even-more-difficult-to-identify females are known by the company they keep.

Sue Hubbell, in Broadsides from the Other Orders, discusses the origin of the word “Katydid.” “Katy” is an olde word for a wanton, and there are associated folk stories/songs about wronged and vengeful women and what they did about it, and katy-did/didn’t echoed society’s debates about the extent of their (alleged) guilt. Elliott and Hershberger, in their excellent book The Songs of Insects, tell an old story of a woman named Katy who was scorned by her lover, who soon wed another. When the new couple was found mysteriously poisoned, the katydids bore witness. But John Bartram, explorer of the American Southeast and contemporary of Ben Franklin, called this insect the “Catedidst,” an allusion to catachesis or instruction by word of mouth, which in turn comes from a Greek word meaning to resound or to din in one’s ears. Ah, the etymology of entomology. One entomologist quoted by Hubbell suggests adopting the family name Katydididae, but no one has taken him up on it yet.

During mating, the male passes a bubble-like sperm packet (spermatophore) to the female; along with his genetic material, this contains protein for her to feast on and use in the development of her eggs. These packets are “expensive;” according to Eaton and Kaufman in the Field Guide to Insects of North America. The male spends as much as 40% of his body weight producing them, and after he hands over a spermatophore, he grazes avidly. Hubbell says that during hard times, when vegetation is sparse, females actively pursue the suddenly-shy males. Because of the high cost (his physiological investment is greater than hers), he is not a wanton.

In late summer or fall, eggs are deposited in or on vegetation via ovipositors that are long and saber-like or short and sickle-like, and they hatch the following spring. Katydids, like other members of the grasshopper clan, practice Simple/Incomplete metamorphosis, and newly hatched nymphs look like their elders and eat the same foods. Nymphs lack the adults’ wings and reproductive organs; these are added gradually as the nymph grows and sheds, and males start to sing as they become sexually mature. The katydid doing chin-ups, whose wings extend only half the length of its abdomen, has almost attained adulthood.

Most katydids nosh on vegetation, but some species are predaceous on other insects, and cannibalism is not unknown. Being large, abundant, harmless and tasty, and in spite of their excellent camouflage (well, except for the pink morphs), they are an important food for birds, including owls and kestrels, for rodents, and for other invertebrates.

Male Katydids are all about sound (in some species, the females answer, but not loudly). And if their hind set of wings is dedicated to flight, their front pair was made for song. This they accomplish by stridulation (friction), rubbing the rigid edge of one forewing against a comb-like “file” on the other. What they produce may not sound like the classic “katy-did, katy didn’t”—that song is limited to the single genus of “True Katydids.” Fork-tailed bush katydids are the best singers of the “false katydids,” with a repertoire of clicks and buzzes. And because those who produce sound must be able to hear it, katydids have a slit-like ear (tympana) on each front leg (look at the pit on each front leg of the katydid that’s facing you). To pick up sound, they raise a leg in a gesture that is reminiscent of humans cupping their hand behind an ear.

Calls are designed to attract females of their own species and to minimize wasting time on other species, and yet if katydids were classified by calls alone, more species would be listed than when they are separated strictly by physical characteristics. Listen to their calls on the Checklist of Katydids North of Mexico site.

Hubbell says that Katydids challenge us to reevaluate our concept of “sound,” because in addition to the clicks and buzzes, some kinds of katydids have an ultra-ultrasonic call, while others produce, by thumping/stamping on twigs in species-specific tempos, vibrations that are detected by other katydids. For many insects there is no line between “heard” and “felt,” and the vocabulary of our sensory experience may be inadequate to express theirs.

Incidentally, the BugLady hopes that BugFans have been enjoying the show put on by the white-lined sphinx moths recently. Find them in late afternoon, at tubular flowers everywhere.

The BugLady