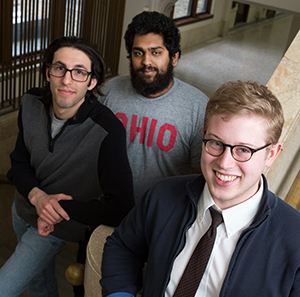

When master’s student Dan Giglio enrolled in a philosophy course taught by Robert Schwarz, he knew “right off the bat” it wouldn’t be an ordinary course. “He had a unique outlook that I hadn’t found in my other professors,” says Giglio.

Schwartz, a UWM Distinguished Professor, approaches philosophical inquiry using a method that had fallen so far out of favor that today’s students might never encounter it. But Pragmatism is back and Schwartz has contributed to its recent revival.

A uniquely American brand of philosophy that flourished in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Pragmatism holds that concepts and theories are best thought of as instruments that can have consequences on current problems. They contribute to a course of action, rather than lead to “telos,” an end or final outcome.

“The aim of inquiry is not the discovery of eternal truths, but the invention of tools to better meet present problems and projects,” says Schwartz.

By the 1940s, Pragmatism was all but forgotten. Many philosophers find Pragmatism unpalatable because it questions the significance of the search for permanent answers to perennial problems, an aim so deeply rooted in traditional philosophy.

“Classical philosophers are looking for truths that are true at all times,” says master’s student Phil Mack of Appleton. “It’s tricky to spell out truth with Pragmatists.”

Darwin and democracy

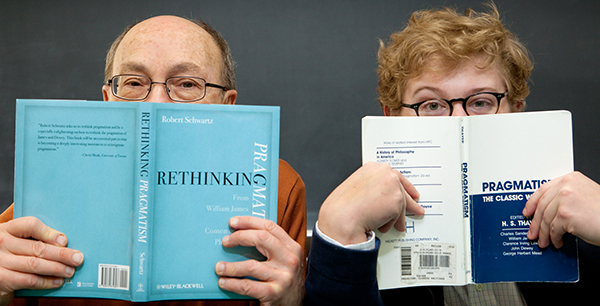

In his recent book, “Rethinking Pragmatism,” Schwartz argues that, just as in Darwin’s day, the pragmatic method continues to offer more insight into the nature of scientific and ethical inquiry than current popular accounts.

Darwinism and other scientific milestones of the time put long-held beliefs about the physical world in serious doubt. “If what Darwin was saying was true, then there would be no telos,” says Mack.

For philosophers, Pragmatism offered a method of working on such questions, while allowing that today’s solutions were likely to be overturned as new evidence was uncovered, that better theories would have to be developed, and that new goals would have to be set.

The acid test for one of the early Pragmatists, William James, was the measure of an idea’s impact, says Giglio. “You ask yourself, is it a difference that makes a difference?”

In the case of science, Schwartz uses the example of the debate in 2006 about whether Pluto is actually a planet. Through a Pragmatist’s lens, the answer is whichever works better in the context of the specific problems being investigated.

Pragmatism, he says, is not an “either/or” proposition, but rather, “it depends.”

“It’s fine to say that science aims at truth,” Schwartz says. “In practice, the most we can claim is that new theories work better than the old.”

Another early Pragmatist, John Dewey, believed that revision was essential to progress – and that the ability of democracies to adjust to change was a powerful justification of their existence.

“It’s fine to say that science aims at truth,” Schwartz says. “In practice, the most we can claim is that new theories work better than the old.”

In response, he founded the “laboratory school” at the University of Chicago at which he could apply his belief that experience is more central to student learning than memorization or other established forms of educational delivery. And he championed the establishment of unions, particularly at universities.

A revival at UWM

Not only is there a resurgence of interest in Pragmatism among scholars like Schwartz, but also among students.

“When I came to the department three years ago, I was the only student interested,” says Mack, who had very little exposure to it in his undergraduate years at Ripon. “Now, there is a whole group of us.”

He thinks students are becoming curious about it not just because of its underdog status, but because of its radical departure from analytic philosophy. Also, Schwartz shows students that they can practice analytic philosophy with a pragmatic filter.

Giglio chose UWM for its highly rated master’s degree program, after earning a double major in physics and philosophy from the Ohio State. He feels lucky to have discovered Pragmatism through Schwartz, and is now looking for a doctoral program that includes some scholarship in the method.

“I just fell in love with philosophy,” he says. “But at times, I worried I was wasting my time because it was impractical to apply it to everyday life. Philosophy offers some fun puzzles, but Pragmatism allows me to look at those puzzles in a more applicable way.”