The sewage sleuth

COVID-19 infection rates vary from location to location, which complicates health responses. But Sandra McLellan knows how to get sewage to talk about it.

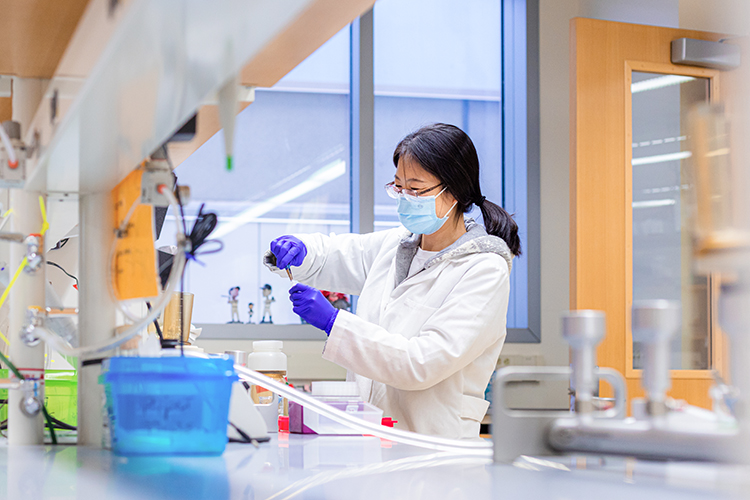

As the COVID-19 pandemic rolled across the United States, Sandra McLellan’s team of researchers began receiving weekly samples of wastewater from treatment plants in Wisconsin’s most populous areas. Using methods they spent months tirelessly fine-tuning, they are extracting genetic traces of a disease that, by the end of 2020, was the leading cause of death in America.

People infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, shed particles of the virus that end up in sewage. Taking recurring samples from a city’s wastewater treatment plants offers a cost-effective, comprehensive picture of the virus’ spread in an entire community. Consistent sampling – what McLellan calls sewage surveillance – doesn’t show how many people in the community have the infection, but it reveals trends that testing alone can’t provide.

McLellan, a professor at the School of Freshwater Sciences, says this type of wastewater-based epidemiology testing can signal when infections are increasing in a city, even though many infected people show no symptoms. As vaccinations roll out, wastewater surveillance can show decreasing virus trends as immunity increases in a community.

In early November 2020, the researchers saw Wisconsin’s COVID-19 surge play out in the wastewater data. “We could just see the concentrations climbing,” McLellan says. “The data is a great complement to clinical testing.”

UWM researchers were among the first scientists in the country to investigate using wastewater monitoring to assist public health efforts around COVID-19. Members of McLellan’s lab began collecting samples from the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District before the state’s lockdown closed schools and sparked droves of people to start working from home. Now, McLellan is helping lead two efforts: one to establish statewide SARS-CoV-2 virus monitoring in Wisconsin and another that creates a blueprint others can use to implement such a program.

McLellan, a Milwaukee native who earned her bachelor’s degree at UWM, returned to the city after completing her graduate work at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. Her lab has established relationships that go back more than 20 years with stakeholders, such as local and state public health entities, wastewater agencies, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “I was attracted back to Milwaukee by the prospect of conducting research on the Great Lakes,” says McLellan, who lives only three blocks from the shore. “But I’ve stayed because of the strong partnerships I’ve found.”

As an environmental toxicologist, she has focused on identifying environmental pollutants and chemicals that can harm human health. But she has more recently become recognized for her research on the health implications of pathogens found in sewage.

In a 2015 study of wastewater from 71 U.S. cities, McLellan and School of Freshwater Sciences Assistant Professor Ryan Newton used markers of human gut bacteria in wastewater to predict a city’s obesity rate with about 90% accuracy. The study gained national exposure because it suggested that large-scale sewage testing could help uncover health issues in a city’s population.

“Sandra’s been one of the world’s experts in understanding not only what’s going on with pathogens in a treatment plant, but also in the pipes beneath our cities,” says Erin Lipp, a professor of environmental health science at the University of Georgia. “She’s been at the forefront of identifying novel markers in sewage, bringing context and understanding to this work. To know what is normally present in sewage is fundamental to understanding what unusual viral loads look like.”

The idea of gauging the prevalence of a viral disease through sewage analysis isn’t new. Public health officials have used wastewater sampling to track outbreaks of diseases that commonly spread through contact with fecal matter, such as polio and, more recently, norovirus.

But there isn’t a standard method for detecting SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater. In fact, it wasn’t even clear that a virus spread through the respiratory tract could be detected in human waste. Traces of the coronavirus shed in sewage are only remnants of the genetic material from the virus, which is likely not viable in the samples. But McLellan and a group of other academic researchers across the U.S. believed it could be done.

“Different types of viruses behave differently in how we isolate them and extract them from samples, and we know very little about how to do this with SARS-CoV-2,” says McLellan, whose lab members worked for months to hammer out technical aspects. “There are many methods to accomplish each step in sample preparation. So we had to go about it systematically to narrow down the best methods.”

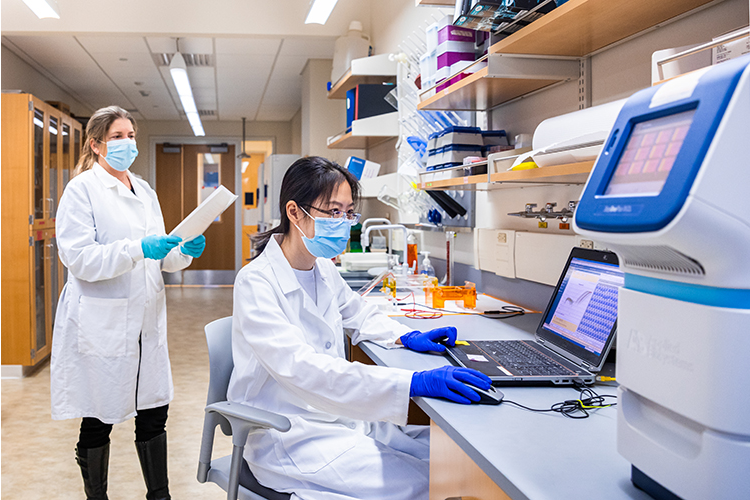

In the summer of 2020, McLellan partnered with the Wisconsin Department of Health Services and the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene (WSLH) to launch a COVID-19 surveillance program that generates weekly data from treatment plants in all but five of the state’s 72 counties.

While McLellan’s lab analyzes samples from the Milwaukee, Waukesha, Green Bay and Racine areas, the WSLH handles samples from the rest of the state. Together, their efforts cover 60% of Wisconsin’s population. It’s the country’s largest program in terms of the number of facilities sampled. Because of that, Wisconsin is one of seven states participating in a nationwide pilot program conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

McLellan’s second wastewater project is centered nearly 900 miles away from Milwaukee. Working with treatment plant operators in New York City and other institutions, she is leading a project to build capacity and help connect public health practitioners to wastewater surveillance system efforts, enabling many more cities to use this method to help manage public health crises.

With funding from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the team’s goal is preparedness for “next time.” Using new COVID-19 surveillance programs at 14 New York City treatment plants, the team is identifying best practices for tracking pathogens in wastewater. In addition to honing technical protocols, the project will work with public health departments to provide information on interpreting results, making it easier for them to transform surveillance data into actionable health policies.

That aspect falls to Dominique Brossard, a UW-Madison professor who examines the intersection of science, media and policy, including how to communicate risk assessment. Other team members come from New York University’s Tandon School of Engineering, Stanford University and the University of Notre Dame.

Lipp believes COVID-19 surveillance has shown scientists that wastewater-based epidemiology is a promising method to track a broad spectrum of viruses in the future, including those that cause anything from Zika to the seasonal flu.

The CDC operates a portal for state, local and territorial health departments to submit wastewater testing data into a national database. The portal may eventually grow into a nationwide effort for pathogen monitoring that would ensure the data could be compared across jurisdictions for use in the next pandemic.

“We’ve learned a lot of lessons,” McLellan says. “Communication and research networks are now in place. Long term, this is developing into a national program.”