Professors like UW-Milwaukee’s Jocelyn Szczepaniak-Gillece are used to hard questions.

But in the course of an hourlong interview to promote her first book, the forthcoming “The Optical Vacuum: Spectatorship and Modernized American Theater Architecture,” (Oxford University Press), one question becomes a stumbling block for this assistant professor of English and film studies: “What’s your favorite movie?”

“Oh my gosh. Oh my gosh. That’s really hard,” Szczepaniak-Gillece replied. “Can I talk about my favorite movie from this summer?” Indeed, she can – Debra Granik’s “Leave No Trace.”

Talking, teaching and writing about the movies in America have been among the film historian’s primary pursuits since Szczepaniak-Gillece arrived at UWM in 2014, and even before then. In 2010, she began researching the life and work of Benjamin Schlanger (1904-1971), whose architectural designs and strong opinions about cinema as art strongly influenced how we watch movies today.

Though primarily an architect, Schlanger was deeply invested in cinema engineering, how people positioned themselves in theater chairs, the size of the movie screen and even how moviegoers behaved themselves when the house lights went down.

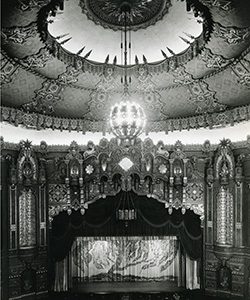

He designed and advised on dozens of theaters across the eastern U.S. and abroad, presiding over the gradual transition from ornate movie palaces and kitsch-cluttered regional theaters to modern auditoriums where all eyes are drawn to the screen. Here, attendees can immerse themselves in a movie, undistracted by their immediate surroundings.

“The central argument of my book is that the impact of film is not only limited to the text,” Szczepaniak-Gillece said. “It’s also about the space in which it’s seen, it’s about the ideologies under which it’s developed.”

While the book is a historical one, Szczepaniak-Gillece thinks her argument, and research, is right for this moment. Milwaukee’s Oriental Theatre, a movie palace built in 1927 – home to East-Indian design flourishes like six golden Buddhas, eight porcelain lions and two minarets – reopens after a major restoration and under new ownership by Milwaukee Film on Aug. 10. Apple has just become the world’s first trillion-dollar business, and its iPads and iTunes make it easy to skip the theater.

“This is a moment that’s ripe for people to reconsider the importance of the place where you’re watching something,” Szczepaniak-Gillece said, “and how it affects your understanding of the text.”

Understand, first, what the movies meant to America in the early 1930s as Schlanger earned an architecture degree and began building his portfolio and writing dozens of journal articles about theater design and engineering.

A film ticket was about 25 cents per person. Hollywood owned the movie studios and many of the movie theaters, and executives worried that if they didn’t make going to the movies “a big event,” then the people wouldn’t come.

Schlanger loved cinema, Szczepaniak-Gillece said, but he didn’t love the way that movie theaters, or “exhibitioners” as she calls them, screened Hollywood films.

“He sees the movie palace, which is elaborate, ornate, over-the-top, exquisite, and Schlanger begins to realize that a movie palace is not proper for suitable immersion in a movie. You walk in and you’re overwhelmed by the vastness of the space, how beautiful it is, how upper class it feels. If you can’t forget your surroundings, he thinks you can’t properly immerse yourself in a film.’”

In those days, theater technology evolved faster than theater architecture. Synchronized sound and improved projection equipment meant that theaters had to be rapidly renovated to meet consumer demand as film quality improved between the ’20s and ’30s. This helped Schlanger advance some of his early ideas, like removing the layers of velvet or velour “masking” that once bordered movie screens, visually and literally distancing the screen from the audience.

Szczepaniak-Gillece’s book chronicles how a major cultural and economic force further elevated the renegade architect’s influence: the Great Depression.

“America’s economic system is totally falling apart, and Hollywood is used to investment from Wall Street,” Szczepaniak-Gillece explains. “Movie attendance drops dramatically, but not as much as you might think; movies are still an affordable luxury for a lot of people.”

Suddenly, the chandeliers, velvet curtains, gilt paint and architectural extravagances “become symbolic of the excesses of the Roaring ’20s that got America into the Depression in the first place,” Szczepaniak-Gillece said.

Then World War II takes hold, jolting America out of the Depression and consuming lots of building supplies in support of the war effort.

Movies matter in the ’40s, but even more so in the ’50s as veterans return to America, build homes and start families. Schlanger remains focused on making the movie theater a place where total immersion becomes possible and where cinema can be appreciated, Szczepaniak-Gillece said, for the art form he believed it to be.

His innovations take greater hold in the ’50s. Szczepaniak-Gillece counts among them the move to wider screens, theater chairs to confine the viewer and direct attention to the screen and theater walls uncluttered by artwork, drapery and other decorations.

As the vestiges of the movie palace are stripped away, American moviegoers increasingly become a version of Schlanger’s ideal spectator.

“That’s the true cinephile: Somebody who sits still, who pays attention, who is quiet and doesn’t get up and move around during the movie,” Szczepaniak-Gillece said. “It’s useful for business and it’s useful for making people respect the product that you’re providing.”

In that way, Schlanger was both a renegade and a conformist. His designs helped create a code of civic behavior for moviegoers in the ’50s and ’60s. Reclining seats and cell phones give today’s audiences more control over their cinema experience, but Schlanger’s influence still looms.

“If we don’t think about theater architecture now, that’s in large part due to his work,” Szczepaniak-Gillece said.

But we should think about it, she added, noting that this is what the book is all about – and something that her students consider each time they screen a film in one of her courses.

“Even in this moment when we’re told that film is dying and the future belongs to prestige television and that all young people care about is YouTube videos, I see something completely different at UWM,” Szczepaniak-Gillece said. “My students are really interested in the importance of film for understanding what it means to be an American and to understand the history of the United States.”