A recent Cheerios commercial featuring a white mother, black father and their daughter attracted a few nasty comments, followed by a huge outpouring of support, with 95 percent of viewers “liking” the commercial.

The recent advertisement is just one reflection of America’s long history of strong feelings about interracial relationships.

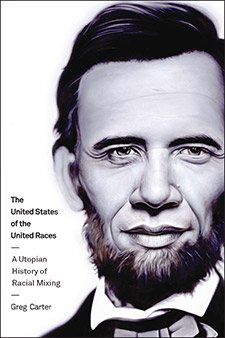

Greg Carter, an assistant professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, traces the history of how such relationships have been both demonized and praised in “The United States of the United Races: A Utopian History of Racial Mixing.” The book looks at the ways Americans have thought about racial mixing from Colonial times to the present.

Greg Carter, an assistant professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, traces the history of how such relationships have been both demonized and praised in “The United States of the United Races: A Utopian History of Racial Mixing.” The book looks at the ways Americans have thought about racial mixing from Colonial times to the present.

“There has been a lot of attention, and an increase in visibility of people of mixed racial heritage,” says Carter. President Barack Obama and golf champion Tiger Woods, in particular, have raised the profile of people of mixed race in recent years. In addition, the Census Bureau and other government agencies have broadened the number of choices people have in filling out the “race” box on federal forms.

An optimistic focus

Carter’s book focuses on the optimistic tradition of racial mixing in the United States, looking at those who saw a racially mixed America as a better America. It’s a topic he originally became interested in and explored in his dissertation at the University of Texas, where he earned a doctorate in American Studies. He now teaches and writes about the issues around mixed race and racial identity.

His students are often surprised at the idea that racial mixing wasn’t always viewed negatively in the past, says Carter. “They often think of the past as a uniformly racist and awful period, but it was much more complex than that,” says Carter.

“Contemporary fascination with racially mixed figures has its historical roots in how past Americans have imagined what radical abolitionist Wendell Phillips first called, ‘The United States of the United Races,’” Carter writes in explanation of the book’s title.

In the book, Carter looks at various historical figures, like Phillips, who took a positive view of racial mingling and saw it as a means to “create a new people, to bring equality to all, and to fulfill a uniquely American destiny.”

He also traces the impact of key Supreme Court decisions, the various ways the public and governments have attempted to define and categorize individuals by their racial mixture, and the impact of historical events in shaping views of racial mixing.

The positive few

From the very beginning, even when sentiment was strongly against mixed relationships, a few influential individuals took a more positive view, says Carter.

While Founding Father Thomas Jefferson warned against whites mixing with blacks and backed state laws against such relationships, his private secretary William Short proposed recognizing mixed offspring, transitioning slaves toward tenant farming and offering universal citizenship.

In the 1780s, J. Hector St. John de Crèvecouer, author of the popular “Letters from an American Farmer,” wrote about America’s mixture of peoples as one of its strengths, according to Carter.

Before and after the Civil War, Phillips tackled the controversial topic of racial mixing head-on. His fellow abolitionists were content to free slaves, but only the most radical of them argued for emancipation, full citizenship and the right to marry whites.

In the early 1900s, playwright Israel Zangwill tried to open a discussion of intermarriage in his play “The “Melting Pot,” but public pressure forced him to remove the play’s Asian and black characters.

By the end of World War II, however, immigration, the Civil Rights Movement and America’s increasing global role had brought more white Americans into contact with other races and cultures, resulting in growing acceptance of racial mixing. Revulsion toward Hitler’s policies of white supremacy also impacted Americans, says Carter. “We required ourselves to be better than that.”

In 1967, the Supreme Court in the case of Loving v. Virginia finally deemed remaining state laws forbidding interracial marriage unconstitutional. However, the ’60s and ’70s also gave rise to a number of movements – black and Latino power, for example – that emphasized the benefits of racial stabilization, casting aspersions on mixing.

A matter of choice

Today, identity among those of mixed race often remains a matter of choice, says Carter. During his 2008 campaign, for example, Barack Obama proudly proclaimed himself the son of a white woman from Kansas and a black man from Kenya. “The campaign was using his mother and father as part of his story, and a progressive view of racial mixing was part of that,” says Carter.

Yet, when Obama filled out his census form in 2010, he identified himself as black. Like many racially mixed people, says Carter, Obama makes different choices in how he wants to identify himself at various times and in different situations. “Identity can change depending on the context.”

While the public now views racial mixing more positively, that alone is not a sign that racism is a thing of the past, Carter says. “We are reaching for a state of more equity and racial progress for minorities,” he says.

However, he argues in the conclusion of his book, attitudes toward racial mixing are just part of America’s shift in the understanding of race.

“We can find figurative power in racial mixing, but as an end it itself, it is insufficient. Mixed race can disrupt the status quo, but not on its own.” To achieve that kind of change, Carter says,” We have to do work.”