In March 2020, UWM faculty faced one of the most difficult challenges in the university’s history.

Suddenly, because of the exploding COVID-19 pandemic, faculty and teaching academic staff were faced with the need to move classes online in just a few weeks. As the pandemic lingered into the fall semester and then into spring again, the need for online instruction continued, even though some classes were offered at least partially in person.

For some classes that involved labs or performances, the transition was particularly challenging. Other classes that were built around small group discussions or that needed focused attention also needed to be modified. Faculty and staff responded with a lot of work, creativity and innovation, according to Diane Reddy, director of the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, and tech support specialists like Kristin Gaura of the School of Education.

While the sudden shift to online was hard, many instructors took advantage of CETL workshops and summer break to rethink and improve their online teaching.

Here are a few examples of how faculty and staff responded.

The challenges

The American Sign Language Studies programs in the School of Education had to be redesigned for the online environment, according to Marika Kovacs-Houlihan and Erin Wiggins, co-coordinators. Both are clinical associate professors.

“Because ASL is a visual language, we require human contact and interaction with our students,” said Kovacs-Houlihan, clinical associate professor. “It’s a 3D language, not a linear language like a spoken language. So, trying to interact with students in a 3D environment, but having to do this in a 2D platform, that made it challenging.”

In addition, ASL requires a high level of eye contact, which is something students find challenging even in a face-to-face environment, according to Kovacs-Houlihan. “Hearing people don’t need eye contact because they depend on their auditory ability,” she said. “They can go ahead and look at something other than the person that’s speaking, and they can still be engaged. You cannot do that in ASL.” For that reason, instructors expect students to keep their cameras engaged to practice this important skill.

Ann Raddant, lecturer in the Department of Biological Sciences, had the dual challenge of running a large lecture class and moving labs either partially or fully online.

Communication was a key challenge, said Raddant, who teaches anatomy and physiology.

“One of my biggest priorities when we moved online was ensuring that students could navigate the Canvas site independently and that the expectations and due dates were very clear. I teach a large enrollment course, so small errors on my end can result in massive floods of emails from nervous students.

“I also wanted to keep myself present in the course and regularly convey that even though we are not physically together, I still care about my students and the goal of my work is to help them learn,” she added. “It is also more difficult to get rapid feedback in an online environment.”

Course design was another challenge for all those interviewed. “A good course guides students through active learning experiences to help them develop a deep and lasting understanding of the content,” said Raddant. “Doing this face-to face is challenging, and doing it online is even trickier.”

Teaching classes that involve small groups or seminars was also a challenge. Mark Harris, professor of geological sciences and vice provost for research, teaches a course on the history of geology.

“I wanted to continue the intense critical thinking and discussion aspect I had done successfully in on-site classes,” he said.

Preparation and organization of the readings was critical, he said. “I needed to be more intentional about it than if the students had been in an ordinary face-to-face discussion.”

With advice from CETL, Harris was able to develop the kinds of questions that kept discussion moving. “We had some technical issues with the breakout groups at first – there was a week when all we got was chirps in the breakout rooms. I couldn’t hear what the students were saying, but they were very patient. I discovered if I used a different browser and some other things, I could get around it.”

Lecturer Hilary Snow teaches art history and Asian Studies in the Honors College. “These are all small discussion seminars, so that was the big challenge making the shift in the spring semester, she said. Rather than lecturing, she would bring the class together in art history, for example, to open a discussion.

“That’s very easy to do in a classroom where you show the image, and it was easy to get a conversation going.” It wasn’t quite as easy online. “When you say something in the classroom, it’s out there, but it’s just transient, but when you type it in, it’s out there in a different way.”

Faculty members found innovative ways to keep their students engaged. ASL Studies decided to include something fun at the start of every lesson. One of the first efforts, involving the whole ASL team, was creating a “percussion song,” using the UWM Panther fight song.

“ASL Literature has a specific device we call ‘percussion,’” Kovacs-Houlihan said. “By creating this percussion song, we share a bit of our culture while making something engaging for the students.”

“It gave us an opportunity to connect with our students,” added Wiggins. “That connection is so hard to do in an online platform.”

Raddant’s students were halfway through the dissection of a pig when classes suddenly shut down in March. “I know many of them were disappointed that they were unable to complete that experience. To compensate for this in the online version of the course, I designed virtual dissection experiences using a program called Anatomy and Physiology Revealed from McGraw Hill. While it doesn’t completely replicate the hands-on dissection experience, it is a decent stand-in,” she said.

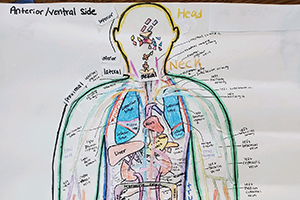

For the anatomy part of the class, she created a project called Virtual Body Builder. “It involved students assembling a drawing of the organs of the body as we studied them throughout the semester. Some of the students’ work is quite beautiful.”

Snow teaches a seminar about the role of museums. However, with museums closed, she switched to virtual tours, had students study how museums were using social media, and scheduled online visits with museum directors and staff, some from as far away as Los Angeles.

“One of my students, in her reflection about the series, said that there was an advantage to it being virtual because we were able to focus on issues and ideas in our conversations rather than just looking at physical objects,” Snow said.

A number of museums nationally and internationally even developed docent-led tours, and the class was able to take advantage of those. For example, Snow was able to take a group on a virtual field trip to an exhibit of Buddhist art at the Freer and Sackler Galleries at the Smithsonian Institution, something she would never have been able to do with an in-person seminar.

Harris organized his 15 students into small groups in virtual breakout rooms for four modules, preparing the readings ahead of time so students were ready for the discussions. He also included a number of questions to go with the assigned reading. “The questions I asked helped prepare them for what they most needed to know for the discussion.

“Because it was online, I needed to be more intentional about it than if they had been in an ordinary, face-to-face discussion,” he added.

Like others interviewed, Harris worked hard to make the class information on Canvas as easily accessible as possible. His daughter’s experience in high school showed him that he could turn off parts of the online learning tool to make it easier for students to navigate.

Communication and feedback from students were essential, according to instructors. Harris, for example, contacted his students the summer before the fall semester, again in mid-August then right before classes started, outlining how to navigate Canvas, and how the class would work.

While all of those interviewed missed the face-to-face interactions with students, they also discovered new tools and ways of doing things that may carry over when classes return to a post-pandemic new normal. Snow helped pilot a new tool called Hypothesis, which allowed student to annotate documents online, even when working in groups, and shared what she’d learned at a CETL workshop in January.

“In my course, it wasn’t a huge transition because I was used to having students read before class, but it forced me to rethink what I had been doing,” said Harris. “In fact, some of that will carry over even when we’re back face-to-face.”