Stoking an Industrial Revolution

UWM’s Connected Systems Institute lays the groundwork for manufacturing innovation.

In Twinsburg, Ohio, Rockwell Automation operates a manufacturing plant where annual costs have been trimmed 4 to 5 percent, on-time delivery has hit 96 percent, and quality is up 50 percent from a traditional plant.

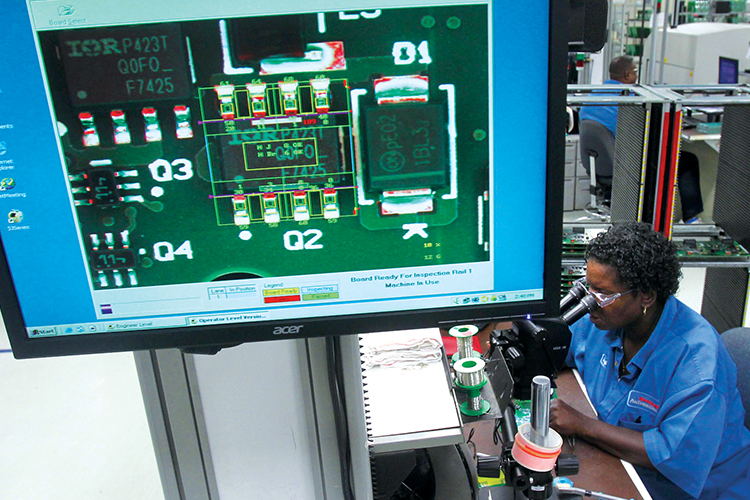

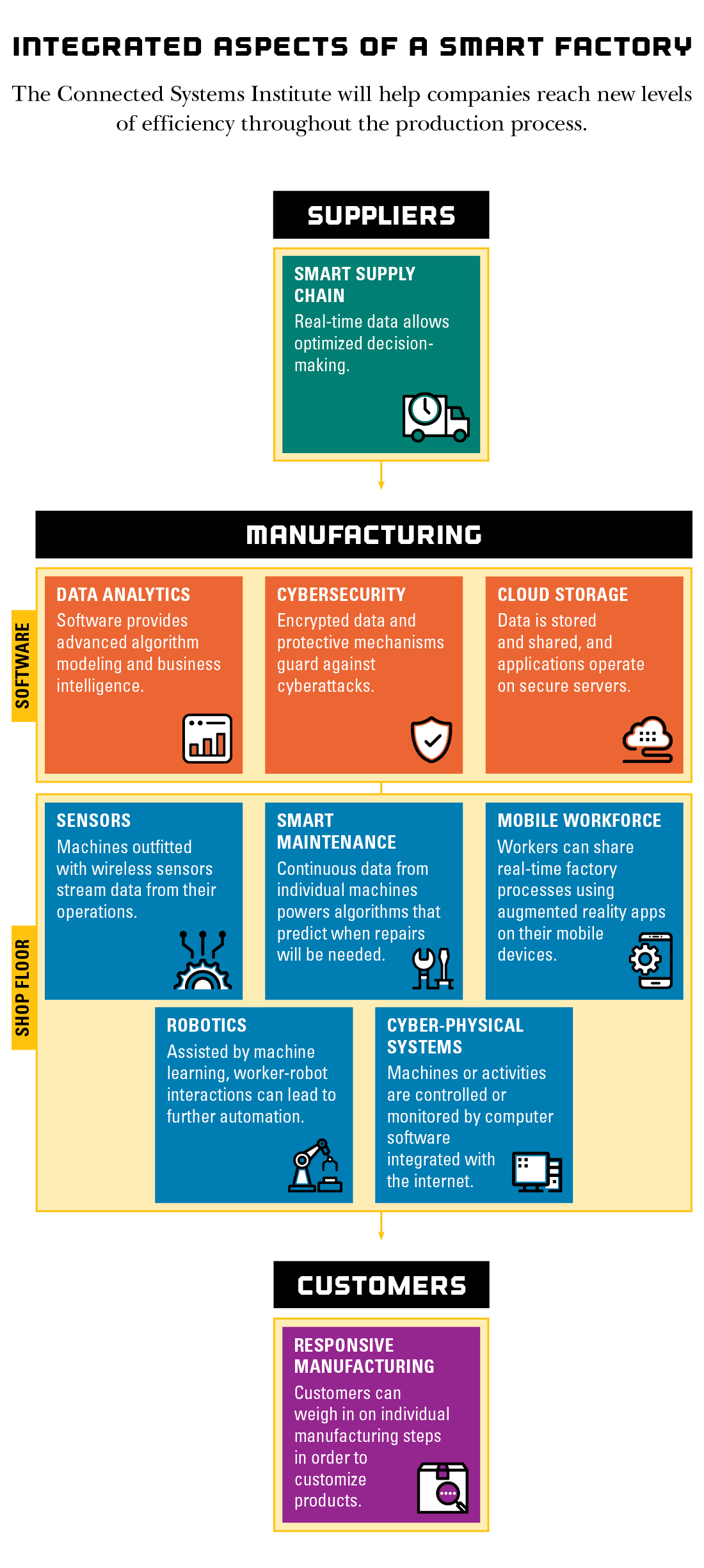

The plant’s individual machines are studded with sensors that collect data and exchange a stream of real-time information online with both people and other machines. All of this data alerts workers when a problem arises. But beyond that, it corrects the issue and informs all processes downstream if adjustments are necessary.

Workers know conditions on the shop floor at any given moment – and so do all decision-makers. The plant is “smart” because it is fully connected.

Rockwell Automation is a global producer of industrial automation and information solutions, and its Twinsburg plant is a prime example of the “industrial internet of things” (IIoT) in action. A cousin of the burgeoning “internet of things” (IoT) – which is fed by 20 billion devices communicating online – the IIoT makes companies more efficient and makes their plants and products safer, all while improving customer satisfaction.

Many believe the IIoT could usher in the next industrial revolution. But that requires the ability to extract specific information from the massive volume of data on demand.

To find the models and technology needed, UWM has launched the statewide Connected Systems Institute.

“Connectivity is unbelievably broad in its scope,” says Adel Nasiri, interim executive director of the Connected Systems Institute. “If you were able to organize all the data streams in the IIoT, it would reveal patterns that point to strategies for increasing efficiency, productivity and safety.”

The institute is a multidisciplinary collaboration involving the College of Engineering & Applied Science, the Lubar School of Business and the Lubar Entrepreneurship Center at UWM, as well as Microsoft Corp., Rockwell Automation, the Wisconsin Economic Development Corp. and other industry leaders.

“IoT is fast becoming a key strategy for companies of all sizes, yet there still exists a gap in cloud skills and training to develop connected solutions,” says Sam George, director of Azure IoT at Microsoft. “The Connected Systems Institute helps bridge that gap by combining advanced research with training for the next wave of innovation with IoT.”

The institute is Wisconsin’s first comprehensive academic-industry consortium involving IIoT technologies. Scholars and industry representatives will collaborate on developing new technology. Companies will be able to test concepts, train employees and share cutting-edge ideas.

The idea for the institute evolved from conversations between UWM and two partners: Rockwell Automation, a major employer of UWM graduates, and Microsoft, whose CEO, Satya Nadella, is a UWM alumnus.

“One of the things we like is the interdisciplinary aspect,” says Tom O’Reilly, Rockwell’s vice president of global business development. “Bringing business, IT and engineering together will make the innovations possible.”

UWM is uniquely positioned to lead the effort. Its faculty are experts in IIoT-related disciplines. It also has strong corporate ties and is located in a key industrial and manufacturing hub.

“This is going to be a world-class center in terms of scale,” O’Reilly says. “It’s great that we’re together in the Milwaukee area. And there is a buzz here, making it a great base to build off of.”

The institute’s core facility will open on campus in spring 2019 in the east wing of UWM’s Golda Meir Library. Long-term plans call for four off-campus test beds where industry partners can experiment and students get hands-on learning.

Making factories smart

One way to think about connected systems is that each physical plant has a digital twin. “Almost like parallel universes,” says Ilya Avdeev, a UWM associate professor of mechanical engineering.

What data are sensors recording? Everything that tracks a machine’s performance over time: energy consumed, operating temperatures, time in use, lubrication and wear, and vibration levels, to name a few. Each machine’s data is incorporated into a picture of systemwide performance. And that system is connected to other systems, which are also streaming similar amounts of performance data.

Such information provides a digital history for every piece of equipment, Avdeev says. Computers can calculate when the machinery will need maintenance or repair and alert a human operator. If one part stops or breaks, the data indicates how to best reorganize the system so it doesn’t fall idle.

The data, grouped in operational networks, can provide big-picture metrics like overall cost savings or comparative data among different plants. But the data also can detect a localized problem and fix it before word reaches the systemwide level. “Edge computing” is the term for the device-level activity, and it makes decision-making much quicker, says Wilkistar Otieno, associate professor of industrial and manufacturing engineering.

For instance, in a production line that recognizes parts by their serial numbers, if machine A doesn’t register a piece, then machine B immediately detects that the piece is missing and alerts workers. Edge software heads off an unfortunate discovery at the end of the production line, and it’s one of the defining characteristics of a connected system.

Another important facet is tracking and tracing processes at any point along the path from product design to customer delivery. Using IIoT data in this manner turbocharges supply chain management by improving coordination of business strategies and the flow of goods from raw materials to inventories.

For example, a multinational dairy could use software to manage big data, allowing employees to track a single gallon of milk back to the cows that produced it. This precision monitoring can be applied to product quality, safety and regulatory compliance, and the company can use such data in its marketing efforts, too.

Cleaning the data

Analyzing data seems like it should be a simple job for computers, but it requires sophisticated data science.

“The data we are handling is high-volume, coming in at a high speed and representing a wide variety – and a lot of it is unstructured,” says Atish Sinha, professor of information technology management in the Lubar School of Business. “Companies have to apply data cleansing, data visualization, data mining and other business intelligence techniques so that management can make sense of it and make better business decisions.”

Sinha directs the Center for Technology Innovation, or CTI, which supports collaborative research projects and workshops on topics such as business intelligence, big data analytics, social media marketing and mobile apps. Faculty and students create interactive tools that help executives see trends and mine data for insight. That includes putting information in accessible online tools, such as dashboards and scorecards, or even advising companies on the best software to accomplish their goals.

CTI’s partners and members include companies such as Northwestern Mutual, IBM, SAP, MGIC and Rockwell. CTI faculty have provided custom training to Harley-Davidson and Johnson Controls executives. Students at the center recently built mobile app prototypes that help MGIC employees track and analyze sales activities.

Sinha says the amount of IIoT data will require novel business intelligence approaches. They must integrate IIoT data from manufacturing, supply chain and sales processes into a usable enterprise resource planning system. These systems pinpoint popular products, explain how to meet demand and indicate if marketing efforts are effective. The Connected Systems Institute will help devise those approaches.

Cybersecurity

All of these enhanced connected systems will need enhanced protection. The broad scope and online nature that makes such global enterprises useful also makes them more vulnerable to cyberattacks.

“The threat of cybercrime disrupting our lives isn’t fiction anymore,” says Lingfeng Wang, UWM associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science. He cites the Petya ransomware attack in 2017, which temporarily paralyzed scores of multinational companies.

Guangwu Xu, a UWM associate professor of computer science, says the security of online data is compromised because some content is publicly exposed during transmission. Cybersecurity experts encrypt data to protect it, but there’s a trade-off for businesses.

“The kind of high-security protocol that protects your bank account, for example, would keep data in an interconnected system safe,” Xu says. “But when that level of protection is used, it slows the transmission speed. So you have to keep a balance.”

Xu and Wang will address such cybersecurity issues within the Connected Systems Institute.

Xu creates tools that better analyze high-dimensional data, in which each sample from an enormous dataset is defined by hundreds or thousands of measurements, usually obtained simultaneously.

Wang’s specialty lies in writing algorithms that anticipate problems so they can be avoided as a system is being built. He’s developed user-friendly tools that, for example, manage the switching of renewable energy sources in smart buildings. The underlying algorithms rely on adaptive learning – engaging the most efficient energy source for the conditions and adjusting as necessary.

In a similar fashion, connected systems use algorithms that monitor data and detect anomalies or vulnerable spots. Custom-made algorithms can be developed at the institute’s testbed facilities.

Training begins now

It takes new manufacturing employees about five years to learn how their jobs directly affect other parts of the company. One of the institute’s priorities is that UWM graduates begin their careers armed with such understanding.

Through the institute, beginning in fall 2019, students can pursue a joint master’s degree in engineering and business that focuses on connected systems. Institute plans also call for other certificate programs and ongoing professional development.

“In manufacturing, there’s a shortage of skilled labor. So automation has to happen; otherwise, companies won’t be competitive.”

But students don’t have to wait to get involved. UWM already offers two courses on industrial connectivity – created by College of Engineering & Applied Science professors Otieno and Naira Campbell-Kyureghyan – and one course on business connectivity – created by Lubar School of Business professors Samar Mukhopadhyay and Sarah Freeman – in partnership with Rockwell.

Also, because the concept of digital manufacturing is evolving so rapidly, the institute is offering a four-day executive education program in spring 2018. Participants will learn how to identify connected systems opportunities in their organizations and apply course concepts to create an implementation strategy.

The timing for a transition is right, says Freeman, associate dean at the Lubar School. Not only are connected systems requiring a hybrid education, but the change is happening at a time when manufacturers are facing the retirement of about 60 percent of their workers.

“In manufacturing, there’s a shortage of skilled labor,” Freeman says. “So automation has to happen; otherwise, companies won’t be competitive. And the smart way to automate is to look at the whole system rather than just replace individual jobs with a machine.”

The concept of connected systems represents a huge culture change for companies, she says, one that affects how employees behave and think about their work, and how they are rewarded.

The magnitude of that shift makes it all the more important that companies are armed with as much knowledge as possible.

“A majority of executives,” Nasiri says, “are interested to know how this will impact their business and create return on investment. They want to determine which components of connected systems they should start or apply.”

Beyond manufacturing

Ultimately, the Connected Systems Institute’s work will prepare manufacturers for the next wave of automation.

Avdeev says that wave will incorporate artificial intelligence into production. Imagine robots that learn from watching human workers, then find further efficiencies as they master a task. And while the institute’s partners will focus initially on manufacturing, the knowledge gained from their collaborative work will help optimize other systems.

The possibilities are vast. In most metropolitan areas, highway sensors and cellphone information on the internet make possible new ways to manage traffic, public transit and parking. Institute discoveries should enable other futuristic city features, such as efficiencies in water and energy infrastructure.

Avdeev also notes the institute’s potential to apply advances in connectivity to the health care field, given the slew of medical devices that exchange data on the IoT.

“Knowing about connected systems has many applications,” Avdeev says. “So if we teach our students the fundamentals of connectivity, they can use that skill in any number of fields