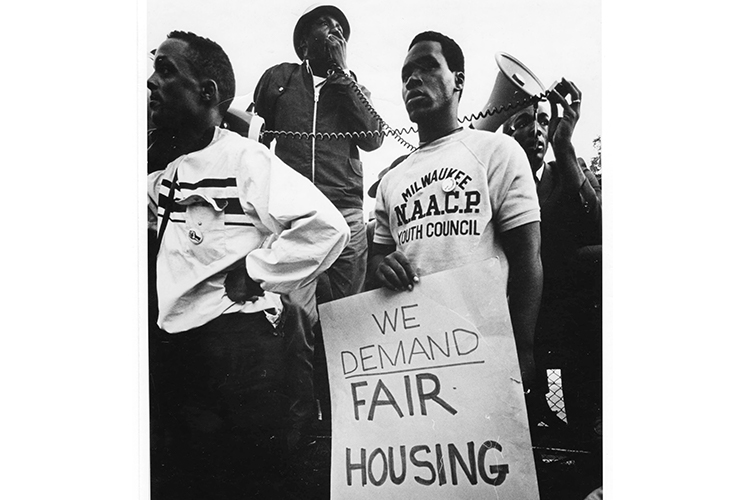

Fair housing now!

A UWM English professor explores how rhetoric shaped resistance to urban renewal.

Derek Handley’s parents were part of the Great Migration, leaving homes in Alabama and North Carolina to head north, where they settled in Pittsburgh’s Hill District. Back in the 1950s and ’60s, the Hill District was a thriving neighborhood, home to Black families that enjoyed the community’s markets and jazz clubs. The downside was that conditions were overcrowded – sometimes you found three families packed into a one-family home, for instance, as more African Americans moved northward to escape persecution and Jim Crow laws in the South, and shady landlords took advantage.

And then the city started to tear it down.

At first, the residents were excited. Urban renewal seemed like a lively era of change in which overcrowded conditions would be abated and the city would construct more and better housing. The reality was much different: Pittsburgh began cutting into the Hill District to build a new arena, and city officials had no intention of accommodating the thousands of people they displaced.

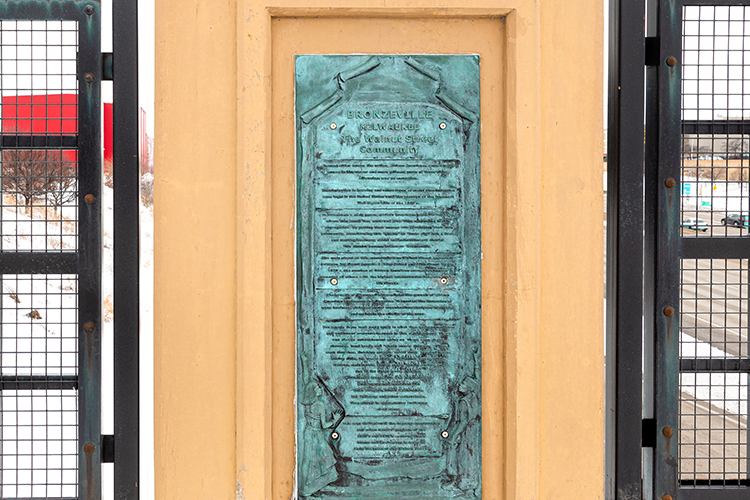

“That’s when things kind of flip,” says Handley, an assistant professor of English in the College of Letters & Science. “Residents claimed this one corner just above where the arena was built. It was renamed, over a period of time, Freedom Corner. It was a site for gatherings, to begin marches into downtown. They actually put a billboard on this corner saying you will not build past this point.”

Handley studies rhetorical strategies that African American communities used in response to urban renewal in the ’50s and ’60s, focusing on Pittsburgh, Milwaukee and St. Paul, Minnesota. He’s collecting his work into a forthcoming book about the history of urban renewal and the Black Freedom Movement.

Urban renewal meant upheaval

Urban renewal swept the nation after World War II. City officials wanted to combat white flight by building new attractions and highways that would connect cities to their suburbs and draw people in. But overwhelmingly, the areas they deemed blighted were in minority communities. And while cities razed homes, they weren’t building new dwellings for the people they displaced.

To compound the situation, there were housing policies like covenants in the Milwaukee suburbs of Shorewood and Wauwatosa that forbade homeowners from selling their homes to Black buyers. This meant African Americans were restricted in where they could live. In Milwaukee, for example, most Black residents were funneled into the city’s north side.

“You take away available housing, and you’re not building enough replacement housing,” Handley says. “So what happens? They pile on into where they could live, which creates some of the same conditions that were problematic before.”

To help tell that part of Milwaukee’s story, Handley is working with Anne Bonds, associate professor of geography, to create a visual depiction of racial housing covenants and resistance to them in Milwaukee County. The project is titled Mapping Racism and Resistance in Milwaukee County.

Faced with discrimination and loss of their homes and businesses, and inspired by the Civil Rights movement sweeping the United States, African Americans began to organize. In Milwaukee, residents marched to protest housing practices, while in Pittsburgh, the sign went up in Freedom Corner.

The rhetoric of civil rights

Two core concepts were at the heart of this resistance to urban renewal. First, Handley says, were demands that African Americans be treated as full-class citizens: “We want equal rights. We want to live like the people in Wauwatosa, or wherever. We have the money. We can afford it. Why can’t we live here?”

The second idea was even more basic: humanity. African Americans argued for their humanity and that these discriminatory practices were fundamentally inhumane.

Organizers used a variety of rhetorical strategies to spread their message. Although Handley certainly respects leaders of the broader Civil Rights movement like Martin Luther King Jr. and Stokely Carmichael, he’s fascinated how local leaders rallied citizens and taught them to advocate for their neighborhoods.

In Milwaukee, local chapters of the NAACP and Urban League worked with faculty from the UW-Milwaukee extension and Marquette University to host leadership seminars teaching protesters how to speak with landlords or at public hearings.

Handley calls this “circulation of agency.” “Part of leadership is empowering other people to become leaders in their neighborhoods and communities, and that’s what I’m seeing by studying these rhetorical strategies,” he says. “Some of the participants in these classes went on to create another organization called WAICO, the Walnut Avenue Improvement Committee Organization. Through their interactions with the city and with the people, they rehabbed houses to get rid of blight.”

In Pittsburgh, another strategy: the use of place, along the lines of the you-will-not-build billboard erected at Freedom Corner. “It was meant to unify the community around this one central part in the city,” Handley says. “In the case of Pittsburgh, they proved to be successful. Officials didn’t do any building past that point.”

The legacy continues today. Freedom Corner is still a meeting place for the Black Lives Matter and Occupy movements.

A personal history, a lasting history

Handley’s personal connection to the Hill District and neighborhoods like it is part of what drew him toward his research focus. Although his older siblings grew up in the Hill District, he did not. In 1968, a few years before Handley was born, the country passed the Fair Housing Act, and his parents moved the family to the Pittsburgh suburbs.

“Which meant, for me, my life was completely different. By the ’80s, if I was growing up in the Hill District, where the crack epidemic ravaged similar communities, who knows what my life would have been like?” Handley wonders. “I’m not disparaging anyone who grew up in urban environments, but it shows one particular effect that the Housing Act had. Members of my family were affected by urban renewal.”

Urban renewal is still going on today, but this time, it’s in the form of gentrification. Younger, usually white and more affluent professionals are moving to cities and buying up housing in areas that have traditionally been minority communities. That, in turn, increases housing costs, often pricing out longtime residents.

And now, just like then, people are beginning to resist. Handley recounts the story of a neighborhood record store in Washington, D.C., that had played music outdoors each day for more than 20 years. People new to the area with predominantly Black residents complained about the noise.

“Their rhetorical strategy of resistance was: Not only are we going to play this music, we’re going to play it louder, and we’re going to turn this block into a block party,” Handley says. “And they rallied around this location as the resistance point of gentrification.

“They said: You will not quiet us. If you want to live here with us, you’re going to accept our cultural norms instead of trying to impose yours. You will not build past.”