Menopause on Your Mind

Neuroscientist Karyn Frick explores how estrogen loss affects memory.

Neuroscientist Karyn Frick began studying how hormones affect memory by watching mice at play. She documented how well they navigated mazes, as well as what happened when they encountered a new toy or how they reacted when the expected location of a favorite toy was changed.

“Mice are curious,” says Frick, a UWM professor of psychology. “By watching them in their lab environment, we could see that female middle-aged mice were mentally old compared to males of the same age.”

But such memory problems don’t stop with mice. In humans, women are three times more likely than men to develop memory loss and Alzheimer’s disease as they age. Frick wants to know why.

Scientists already know memory deficits are linked to a decline in estrogens, hormones whose levels plunge during menopause. Estrogens enhance male memory, too, and testosterone is converted to estrogens in their bodies for that purpose.

As with most things regarding the brain, though, researching the answer is not so simple. You can’t just replace estrogens to solve memory problems, and hormone replacement therapy for menopausal women can carry harmful side effects, such as an increased risk of cancer and cardiovascular problems.

Frick’s goal is to identify potential new drugs for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, ones that don’t carry dangerous side effects and are equally effective for men and women. To do that, she’s unraveling the intricate chain of cellular events through which estrogens enhance memory.

So far, she’s found that gender makes a big difference in the process. Complicating matters, estrogens act differently on mice of different ages and mice that have differing levels of mental stimulation.

It’s a puzzle, not unlike those mazes the mice must navigate.

In her undergraduate years at Franklin & Marshall College, Frick decided to pursue psychology. Then as now, complexity was part of the appeal. She relishes fitting the puzzle pieces together.

“For me, the research is like detective work,” she says. “What’s really exciting is when you read something that triggers an ‘I wonder what would happen if…’ moment.”

A fellow of the American Psychological Association, Frick was recently named Investigator of the Year by the Alzheimer’s Association’s southeastern Wisconsin chapter. She’s compiling and editing a book detailing the role of estrogens in cognitive functioning, and through her teaching and mentorship, she’s inspired hundreds of students, particularly women and minorities, to pursue careers in neuroscience.

“It’s a powerful motivator for me and my students to know that our findings could ultimately help people.”

“Karyn is considered a global expert on how estrogen hormones affect memory,” says Joanne Berger-Sweeney, Frick’s postdoctoral mentor at Wellesley College and now president of Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut.

Frick’s research focuses on the brain’s hippocampus region, which is crucial for memory and deteriorates with age and Alzheimer’s disease.

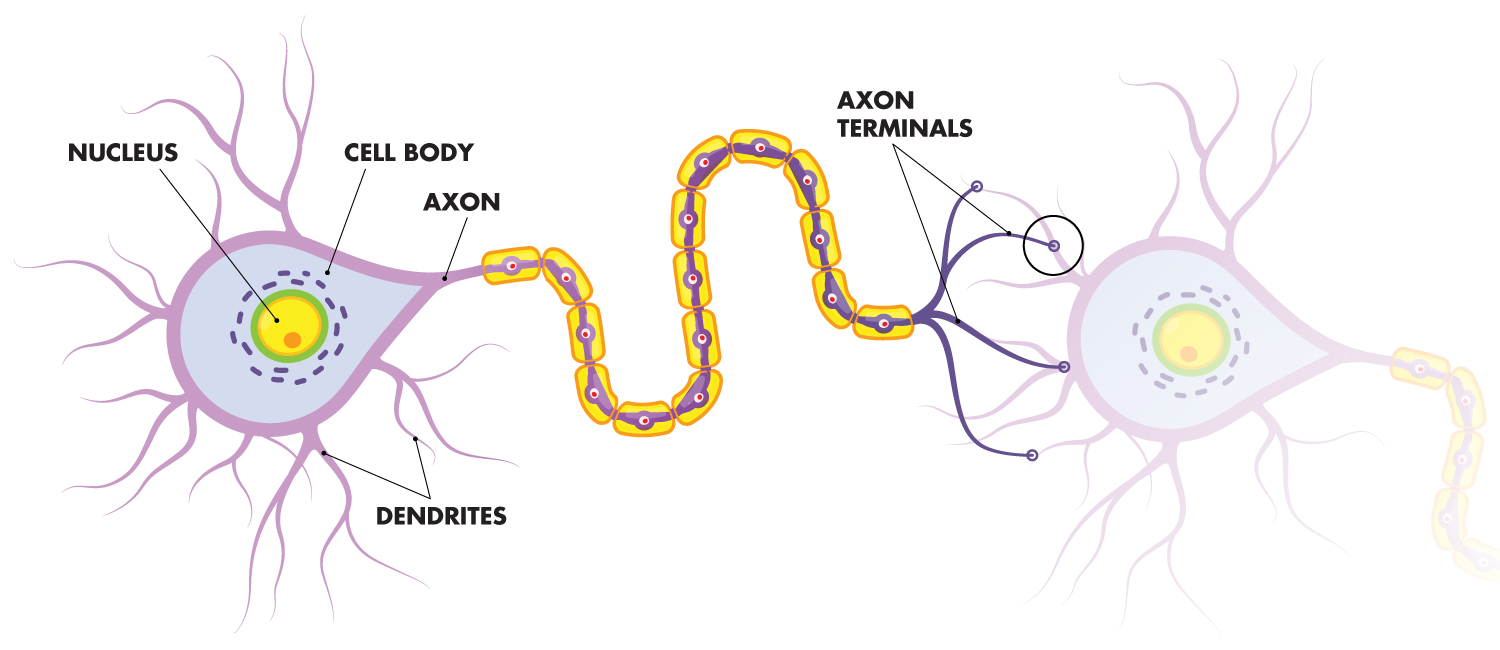

In the brain, signals are sent along “relay stations” between two neurons. The highway for this transport, called the axon, ends at either the outer membrane of the receiving neuron or one of the receiver’s many dendrites. Fringed with extensions that resemble tree branches, dendrites are docking points that play a central role in memory. Frick’s team studies what happens on the molecular level at these docking points.

Chemicals called neurotransmitters direct brain communication, and they’re activated when binding to their receptors. Proteins, which carry out genetic instructions, are also part of the cellular machinery, and their work can be influenced by estrogens. When estrogens are involved in the communication process, it improves the outcome, such as helping form a longer-lasting memory.

But estrogens aren’t as plentiful in the body when menopause arrives, so memory problems arise. “It’s not like menopausal women can’t remember anything,” Frick says. “But with estrogens, they remember better.”

Frick took significant steps toward figuring out the puzzle in 2013. For estrogens to be effective, they must attach to specific receptors within the dendrite and the cell wall. Frick’s research team discovered that in order for two receptors to carry estrogen’s message to proteins inside the cell, a third receptor – for the neurotransmitter glutamate – must also be involved.

The combination unleashes a cascade of cellular signaling that enables a protein, called ERK, to enhance memory. Frick’s study was the first to link estrogens to one of the chemical processes known to create memories.

Frick’s latest research has revealed some crucial differences in the memory process for women and men. She’s discovered that, in women, the presence of estrogens links the hippocampus to a different part of the brain – the prefrontal cortex, where long-term memories are stored – and boosts memory mechanisms in both areas.

Frick also has found that the activation of ERK in women occurs at the neuron’s membrane. That’s important, because proteins in the membrane are better drug targets than those inside the cell.

With partners at other universities, Frick is helping kick-start the pharmacology for drug development by testing compounds that bind to one particular estrogen receptor and mimic the effects of estrogens. Early testing of one such compound delivered promising results in female mice.

But when Frick and postdoctoral fellow Wendy Koss investigated the signaling chain in male mice infused with a potent form of estrogen, they got a surprise: It doesn’t happen through ERK activation as it does in females.

“If the biochemical events leading to enhanced memory are different,” Frick says, “then you may need to develop drugs tailored to the mechanism specific for each gender.”

The gender issue is magnified when you consider how important estrogens are in other areas of women’s health. Estrogens are needed to maintain bone density and healthy cholesterol levels, and are linked to the incidence of depression and other mood disorders. But they have adverse effects on the vascular system and promote some kinds of cancer. All of those factors must be taken into consideration when trying to solve the estrogen-memory puzzle.

And Frick notes another complicating factor: One reason, she says, so little is known about estrogens’ effects in the body is that, for decades, researchers excluded females in order to simplify their studies.

As a result, medical research is missing vital details on diseases or conditions that manifest differently in women and men. That’s led the National Institutes of Health and the Federal Drug Administration to establish new policies intended to close the gender gap in medical research.

Frick’s work is a crucial part of that process and part of a broader health conversation. “Few women are aware of the importance of talking about hormone replacement therapy with their physicians if they have a family history of Alzheimer’s,” she says.

And yet, some of her research has shown such therapy only supports memory if begun at the onset of menopause. Beginning the regimen later actually has detrimental effects on memory.

“It’s a powerful motivator for me and my students to know that our findings could ultimately help people,” Frick says. “Every finding allows us to see a new aspect of the puzzle and then put the pieces together.”