Thanks to improvements made to UWM’s award-winning Spiral Garden last year, the landscape feature now diverts even more runoff from rushing into the sewers during a heavy rain than before – about 10,000 gallons over the garden’s prior capacity.

That translates into containment of an extra half-inch of rain falling on Lot 18, which is adjacent to Norris Health Center and the north side of Holton and Merrill halls.

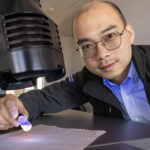

The Spiral Garden is the centerpiece of a 41,000-square-foot zone, nestled among the Klotsche Center, Norris Health Center and the physical plant, where professor of architecture James Wasley began designing a stormwater management system in 2006.

The zone includes a 358-linear-foot system of vegetated bio-swales, sunken gardens lining the parking lot and a 5,000-square-foot garden containing deep-rooted native plants that descends in elevation to form a kind of giant natural bathtub.

As of 2013, the garden also features two 20-foot cisterns that together can hold 12,000 gallons of runoff diverted from the roof of the physical plant.

“The point was to slow the water down as it rushed toward the flood-prone intersection of Edgewood and Downer avenues, where the pipes in the street were easily overwhelmed during storms,” Wasley said.

With partnership funding from the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District, UWM and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, construction on the Spiral Garden began in 2009 and was completed in 2014 – except the two most recent improvements. In 2017, those features – a new stone weir wall and a raised drain on the deepest part of the spiral garden – were added.

About 100 students have worked on the project since its inception.

Wasley said the final features are able to hold about twice the additional capacity that was originally estimated. Figuring the capacity of the whole system, however, is more difficult. While he has plenty of evidence that the system is working, Wasley said, he and his students have not been able to quantify how much water evaporates and how much seeps into the ground.

“We know it it’s doing the job of containment and that it’s benefitting the MMSD’s deep tunnel by curbing sewer overflows in the area,” he said. “It’s also a magnet for native birds and bees.”

Wasley is lead author of a “zero-discharge” stormwater master plan for the UWM campus that also led to the installation of green roofs on the Sandburg Commons and the Golda Meir Library.

He also designed a stormwater fountain at the corner of S. First Street and E. Greenfield Avenue that gestures toward the UWM School of Freshwater Sciences, and a companion fountain that will be installed at the west entrance to the school in the spring of 2019. At the fountain, water discharged from the aquaculture tanks inside the building will spill into a reflecting pool filled with native aquatic plants and then drain to the lake.