Two former UWM students will be watching their work on the big screen this weekend when the Milwaukee Symphony performs the live soundtrack to the cult Halloween classic “The Nightmare Before Christmas” at the Riverside Theater.

Before Owen Klatte and Angie Glocka were busy movie studio animators, they spent several years in the late ’70s taking film classes at the Peck School of the Arts and working at what was then Wisconsin’s only animation studio.

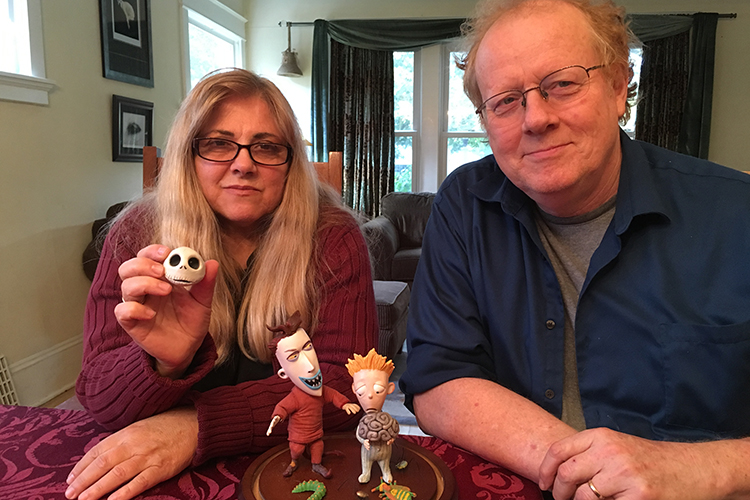

The couple estimate that between the two of them, they animated about 15 percent of the unlikely hit about the collision between Halloween Town and Christmas Town. As an aspiring animator but, in his own estimation, not a very good artist, Klatte found a niche in stop-motion, the painstaking process in which a puppet’s limbs and face are moved a fraction of an inch by hand for each frame of film. “A good animator can do five seconds a week — in a good week,” Klatte said.

Klatte graduated from UWM in 1976 with an architecture degree, figuring it was a field where he could be just good enough at both art and engineering. “Lots of animators come out of architecture,” he said. “It speaks to both sides of the brain.” But although he never wanted to be an architect, “I learned a lot about design and how to work hard.”

When they moved west without film degrees in 1982, their destination was the Bay Area rather than Hollywood — it was where they could seek out George Lucas, Pixar, a predecessor of DreamWorks, and lots of work with the Pillsbury Doughboy, the California Raisins, and “the whole period of dancing food commercials,” Klatte said.

But it took them several years to find regular work in the field before “Nightmare” producer Tim Burton and director Henry Selick began hiring talent for the multi-year project in the late 1980s. “To this day, it’s the hardest job I’ve ever had,” Klatte said. “But we didn’t know it would be a classic. Disney didn’t know what to do with it.”

After characters are built and painted in one shop and costumed in another, and after a miniature set is built and lighted, it’s the animator’s turn. Although each character has many different heads and mouths to capture every possible expression, “the puppets often break in the middle of a scene,” Glocka said. “That was a trick, swapping them out so it didn’t look like a mistake.”

One challenge for “Nightmare” was that Burton designed the characters with very small feet — too small to balance the weight of a puppet. The solution was to bolt the feet to the floor, which in turn meant drilling a hole in the bottom of the set for every footstep.

Klatte has kept a chart for one shot from “Nightmare,” which was 15 seconds of dialogue between Jack Skellington and Sally. Half a dozen 11×17 pages detail frame-by-frame movements for face, body, right hand, left hand. “The puppets have to hit their marks like a regular stage mark,” Glocka said. The director would stop by every day to talk about progress, but otherwise, once the scene is set up, stop-motion is a pretty lonely process.

“I had a scene with 15 characters moving at the same time,” Glocka said. “That’s when I started going gray.”

Like everything else, stop-motion has changed with technology — video assist is a faster and easier way to measure movement than the old metal gauges. But Klatte thinks computer-generated animation will never replace it entirely.

“Everyone remembers the crushing day when we found out that ‘Jurassic Park’ was going to be done with computers,” he said — the original plans for the 1993 dinosaur epic had actually called for stop-motion. “But it hasn’t killed stop-motion yet. It’s still cheaper, and it has that hands-on aesthetic. People like that funky look.”

After “Nightmare,” Klatte worked on “James and the Giant Peach” and Glocka worked on “Toy Story,” among other credits. They moved to Southern California in 1998 and spent a decade doing mostly computer animation, including “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows,” for which Klatte supervised all shots involving the dementors.

But movie work involved more and more travel — the “Harry Potter” work meant six months in Australia — and the couple decided to make a change in 2013. They moved to Shorewood to be close to family and to “watch a Packer game without driving cross-country,” Glocka joked. Their daughter, Julia, graduated from Shorewood High School in 2016.

While Glocka is busy with gardening and beekeeping at her late father’s house in West Allis, Klatte now teaches animation part-time at UWM. His average load, he said, is teaching introduction to stop-motion every semester, and somewhat less often, the business of animation — “because I’ve been a boss, I’ve started studios. I tell them how to put together a good demo reel, and where the industry is and where it’s going.”

This story originally appeared in different form on the Milwaukee Symphony website.