By providing training and access to employment opportunities, job programs help individuals obtain the skills and social connections necessary to achieve sustainable employment.1 The structure and function of these programs vary, though many serve low-income adults with limited education and job training. Despite their public appeal, most job programs in the US struggle to sustain impact over time, as gains in employment and income among program participants seldom last more than six months.2

There are several reasons why these programs often do not produce long-term benefit. First, job programs rely on a pool of low-skilled positions into which they place participants for training and development. However, the availability of low-skilled jobs is shrinking due to automation and out-sourcing.3 Second, employment service participants of color often face systematic discrimination when attempting to land employment, undermining their efforts to attain economic self-sufficiency.4 Finally, personal health challenges and risk factor profiles sometimes sabotage low-income job seekers’ attempts to sustain long-term employment. For instance, studies have shown that these job seekers endure stress and trauma at much higher rates than the general population; in addition, their experiences of adversity impair physical and mental health, which exacerbates problems with work.5,6 To address the health and employment effects of trauma, innovative trauma-responsive employment service programs have begun to emerge.

In order to enhance the well-being of their trauma-affected clients and increase the chances that clients will obtain and sustain meaningful employment, these programs integrate key components of trauma-informed care (TIC). They combine, for instance, hallmark TIC principles such as empowerment and peer support7 with emerging TIC practices such as trauma screening, referral to services, and use of evidence-based trauma interventions.8 Results from a few published research studies suggest that such programs promote positive long-term outcomes:

- A welfare-to-work program, serving low-income mothers of young children, introduced several key trauma-informed components to their menu of services: financial empowerment training and the well-validated peer support Sanctuary Model®. The program helped to reduce participants’ depression symptoms while increasing income-benefits that endured well after services ended.9

- An innovative supported employment program, serving military veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder, provided immediate and extensive mental health referral services along with case management services. An additional key program component, rapid job placement, aimed to facilitate self-empowerment and self-efficacy. Evaluation results indicated that the program increased participants’ earnings over a long period.10

Healthy Workers, Healthy Wisconsin

In 2017, Community Advocates Public Policy Institute partnered with the Institute for Child and Family Well-Being to launch Healthy Workers, Healthy Wisconsin (HWHW), a five-year project designed to increase low-income job seekers’ access to trauma-responsive employment services. Funded by the Wisconsin Partnership Program and Bader Philanthropies, HWHW integrates trauma-responsive practices within various employment service programs located in Southeast Wisconsin. Types of participating programs include welfare-to-work, non-traditional transitional jobs, and prison reentry. At the heart of the initiative, which runs through 2021, is a protocol titled trauma screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment or T-SBIRT.

T-SBIRT

The T-SBIRT protocol is a brief, standardized intervention that integrates trauma-informed care principles and practices into its structure. By directly addressing trauma exposure and its effects, T-SBIRT works to remove critical barriers to health care access. Within employment services, the protocol requires approximately 30 minutes to complete and consists of a number of steps including the following.

- Screening for healthcare access, trauma exposure and trauma symptoms

- Probing for helpful and unhelpful stress coping skills

- Enhancing motivation for help seeking behavior

- Referral to health, mental health, behavioral health and/or social services

Evident in the structure of T-SBIRT are hallmark TIC principles and practices such as screening and assessment, a focus on stress coping, client empowerment through motivational interviewing, and referral to treatment and other services (see issue brief in Trauma Responsive Practices). In fact, T-SBIRT providers work closely with referral partner agencies that offer well-validated services, including trauma-specific mental health treatments that reduce PTSD symptoms. Participating employment service agencies also collaborate closely with their employer partners to enhance the trauma-informed nature of stability employment. As such, T-SBIRT and HWHW rely heavily on interagency collaborations, another critical feature of TIC.

HWHW Results

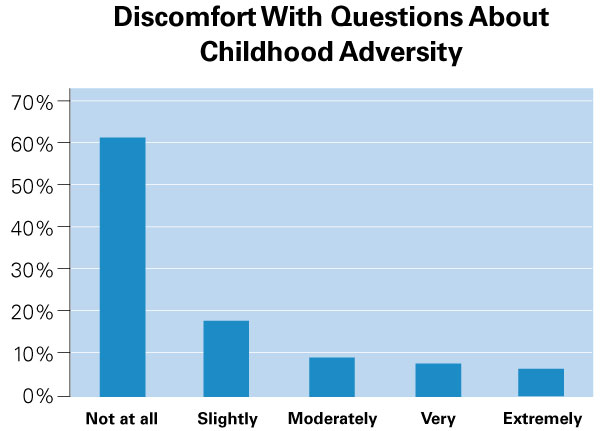

A recent study of HWHW showed that it is feasible to implement T-SBIRT within employment services.11 Several non-traditional stability or temporary jobs programs were the subjects of the study. Expanding the range of programs and number of participants, the authors have conducted ongoing analyses of HWHW data. Results suggest that the protocol was acceptable or tolerable to the 186 project participants. Fully 94.1% of the sample reported feeling the same or better after completing T-SBIRT services, consistent with other research showing that respondents typically experience little to no distress when discussing past trauma exposure in the context of a well-conducted interview (see Asking Sensitive Questions Issue Brief).

Moreover, T-SBIRT addressed common problems among participants, meaning that was suitable for the client group. For instance, 96.6% experienced significant trauma in their lives, and 55% screened positive for post-traumatic stress disorder. Other mental health problems appeared to plague a relatively large portion of the study sample. Over forty percent screened positive for depression, and nearly half endorsed problems with anxiety. An additional barrier to health and well-being that T-SBIRT targets is access to healthcare, and over one-third or 37.7% of the participants indicated that they had no regular place to go for healthcare.

Designed ultimately to facilitate referrals to outside health-related services, T-SBIRT appeared to function as intended with employment service recipients. Nearly three-quarters of the study sample accepted a referral to any type of service. Over half accepted a referral to mental health care, which is surprisingly good news given the stigma that such services carry among low-income groups.12 Finally, over one-quarter of the project participants accepted a referral to primary healthcare services.

Conclusion and Future Directions

As evidenced by the feasibility study results, T-SBIRT shows promise as an efficient, user-friendly tool that employment service providers can implement in non-clinical settings to connect clients to appropriate services such as primary and mental healthcare. If shown to produce meaningful health and employment outcomes, T-SBIRT will have significant implications, not only for individual at-risk job seekers, but also for their families and entire communities suffering from the interrelated cycles of poverty, unemployment, poor health, and untreated trauma.

Currently, ICFW is conducting an impact study to explore whether completion of T-SBIRT within employment services is associated with improved health and employment outcomes. Focus groups with program participants have also been completed in order to assess program satisfaction and explore recommended improvements. In addition, HWHW administrators continue to search for trauma-focused mental health referral partners given the high demand for yet limited supply of such services. Program administrators are additionally involved in collective efforts to define trauma-informed employment practices.

Finally, the ultimate goal of HWHW is to stimulate policy change such that state-run employment services become more trauma-responsive. Implementing T-SBIRT along with other HWHW recommendations will potentially promote more responsive and effective employment services. Therefore, Community Advocates Public Policy Institute in tandem with the Institute for Child and Family Well-Being is disseminating results of the HWHW initiative to policy makers and the public at-large.