Housing provides a foundation for health, well-being and prosperity. However, many families in the child welfare system lack reliable access to an affordable home. In this issue brief we highlight how housing is linked to child safety, permanence and well-being, and call for child welfare practices that promote safe, stable, and healthy housing.

Inadequate Housing Undermines Safety, Permanence, and Well-being

The root causes of child abuse and neglect are complex, with poverty, substance use and mental illness counting among the many known risks to child safety. Although inadequate housing has received less attention, studies have shown that overcrowding, eviction and homelessness are associated with an increased risk of abuse and neglect.1,2 Corresponding evidence suggests that providing assistance with housing and other concrete needs (e.g., clothing; furniture) may reduce the risk of abuse and neglect.3

Along with its threats to child safety, poor housing jeopardizes family preservation and child permanency goals. Among families that are referred to child protective services, those with a history of housing instability and homelessness are at a greater risk of having a child removed from their care.4 Housing problems can present barriers to family reunification as well.4,5 In sum, inadequate housing may contribute to entering the child welfare system and difficulty exiting the system.

Unsafe, unstable, and unhealthy housing also comes at a significant cost to child well-being. The effects of inadequate housing can be insidious, meaning that the immediate consequences are imperceptible, yet the long-term consequences are dire. For example, exposure to unsafe physical conditions such as the presence of toxic hazards (e.g., lead, asbestos) can, over time, lead to respiratory diseases, reduced brain volume, and intellectual impairment.6,7 Similarly, housing instability and homelessness is a source of significant family stress, which, in turn, impairs children’s neurobiology, immune system functioning, as well as cognitive and social-emotional development.8

Poverty, Housing Instability, and Child Welfare System Involvement in Milwaukee

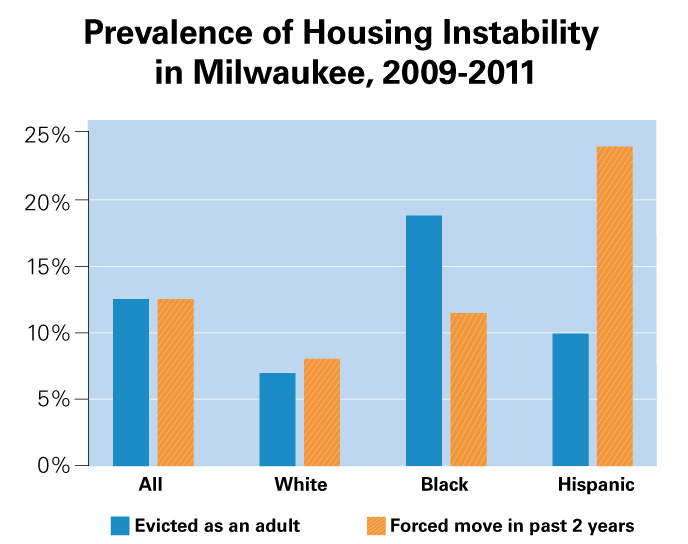

Like many other cities across the country, Milwaukee faces a housing crisis. As shown in the figure below, a startling percentage of city residents are regularly evicted or forced to move. The figure also reveals that housing instability is unevenly distributed among racial and ethnic groups — differences that are associated with disparities in income and wealth as well as a lack of affordable housing stock. According to the most recent U.S. Census data, the poverty rate in Milwaukee for blacks was about 40%, for Hispanics it was nearly 32%, and for non-Hispanic whites it was less than 15%. The crisis in Milwaukee also stems from a shortage of affordable housing for low-income families, reflecting a nationwide trend where “the majority of poor renting families spend at least half of their income on housing costs.”9

Matthew Desmond’s Milwaukee Area Renters Study found that a significant percentage of rental property occupants had been evicted as adults, and another significant proportion had been forced to move in the past two years.

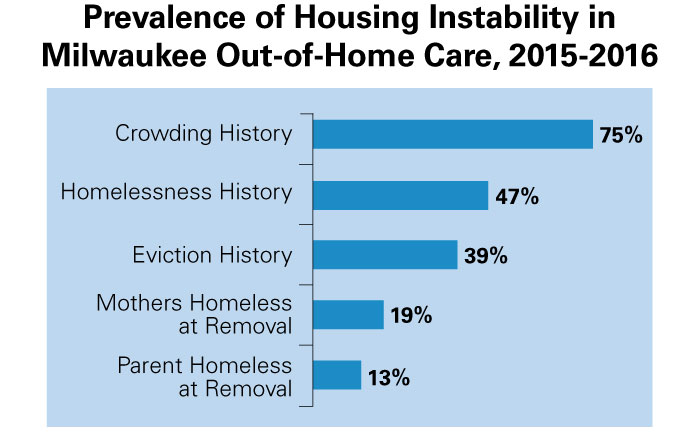

For families in the child welfare system, especially those with children placed in out-of-home care, problems with poverty and insecure housing are particularly acute. For example, one study in Milwaukee by Courtney et al.5 showed that, compared to families receiving voluntary in-home services, families with a child in out-of-home care were almost twice as likely to have been evicted and almost three times as likely to have been homeless in the prior year. Supporting these findings, recent data collected by Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin (see figure below) demonstrate that children who are placed in foster care in Milwaukee often come from families who have a history of overcrowding, eviction, and homelessness.

Source: Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin Well-being Assessments

Addressing Housing Needs in the Child Welfare System through Evidence-Based Service Planning

Because many families in the child welfare system present with complex needs, including barriers to housing, comprehensive service plans are often prepared. Increasingly, however, the field is moving toward an evidence-based service planning (EBSP) approach,11 which recognizes the following: (a) child welfare systems have limited resources, (b) clients can be overwhelmed by demanding case plans, and (c) targeted, brief services can be as effective, if not more so, than comprehensive, long-lasting services. The EBSP approach also acknowledges that child welfare systems have an ethical responsibility to prefer practices with a record of effectiveness over unproven practices, and that the most basic and exigent family needs should be addressed first. Thus, child welfare agencies have an obligation to use, whenever possible, evidence-based and evidence-informed assessment, referral, and case management practices.

Assessment, Referral, and Case Management Practices

Child welfare systems are required to collect extensive data to document their performance on indicators of child safety, permanence, and well-being. While considerable child-level information is typically collected, robust assessments of family needs and strengths are often lacking. Recognizing this information gap, the well-being unit at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin launched a new initiative in 2015 whereby child and parent well-being assessments are completed with all families that have a child placed in out-of-home care in Milwaukee. Information on housing and other family needs is collected at multiple time points in order to enhance initial risk assessments, service planning, and progress monitoring.

Once an initial assessment is completed, however, child welfare agencies typically are unable to provide intensive, concrete forms of housing assistance. At minimum, child welfare agencies should have a prepared resource guide that staff can use to facilitate referrals to local sources of housing support. However, a single referral may not be enough to ensure that families receive the support they need. When they seek housing support, families often face a lengthy intake, search and application process, and housing programs may not have the capacity to engage families for the time necessary to help them secure a stable residence.

Therefore, child welfare agencies may need to collaborate with systems and organizations that specialize in housing and other basic needs. Supportive housing programs are emerging that facilitate cross-system coordination of housing support and other community services such as trauma-informed mental health and substance use services.12 Similarly, the Family Unification Program, sponsored by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, promotes coordination between child welfare agencies and housing authorities to increase access to subsidized housing.13 Expanding the scope of child welfare case management to include enhanced communication and even co-location with housing support programs could improve the likelihood of a successful transition to a safe, stable, and healthy home.