Why Does Assessing Well-Being Matter?

Most children and adolescents that enter the child welfare system have been exposed to multiple adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), including abuse and neglect. As a result, they often present with neurobiological, cognitive, and social-emotional deficits that are likely to undermine their long-term health and well-being in the absence of effective services.1,2 Unfortunately, evidence-based interventions are implemented infrequently in child welfare settings.3

Child developmental screenings coupled with clinical and functional assessment practices are critical first steps in the intervention process.4 In addition, gathering information related to family and community assets can help to reinforce multidimensional and age-appropriate child assessments.5 This issue brief describes a strengths-based and family-focused approach to assessment and intervention that has been developed by Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin to promote the well-being of children and adolescents in the child welfare system.

Child-Well-Being: A National Movement

There is widespread agreement that the child welfare system should work to ensure that children live in a safe and stable environment. For several decades these goals have been codified in federal legislation including the Child Abuse and Prevention and Treatment Act in 1974 (P.L. 93-247), which set minimum standards for abuse and neglect and supplied funding to the states for its prevention, assessment, investigation, and treatment. Subsequently, the Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act (1980; P.L. 96-272) provided states with economic incentives for family preservation services to keep families together while minimizing the length of time and number of placements that children experience in out-of-home care.

It was not until the passage of the 1997 Adoption and Safe Families Act (P.L. 105–89) that federal child welfare statutes began to prioritize child well-being. Despite this welcome shift, the field has been slow to integrate this goal into child welfare practice and policy, due in part to a lack of consensus on how to define and measure well-being or whether it should stand alongside safety and permanency as a statutory goal of child welfare.6 There are signs, however, that the movement toward well-being is beginning to gain traction. For example, in 2012 the Administration for Children, Youth and Families (ACYF) issued a memorandum titled Promoting Social and Emotional Well-Being for Children and Youth Receiving Child Welfare Services7 that highlighted the impact of ACEs and toxic stress on child development. Among its recommendations, ACYF called for the routine use of trauma screenings and functional assessments to measure child well-being along with the implementation of validated interventions to promote well-being.

The Well-Being Assessment Program: Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin

Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin has responded to the call for improved screening and assessment practices in child welfare by designing and implementing a Well-Being Assessment program that is integrated and coordinated with prevention and intervention services. The program is based on three basic assumptions about well-being. First, assessments should attempt to understand the whole child. Therefore, to assess well-being it is important to measure child development and functioning across multiple domains (e.g., physical; cognitive; social-emotional). Second, assessing well-being requires evaluating the child in context. For this reason, any assessment of child well-being is incomplete without information about the child’s family and home environment. Third, well-being is a crucial focal point for child welfare systems to address, one that is linked to long-term child outcomes that extend past a child’s time in foster care.

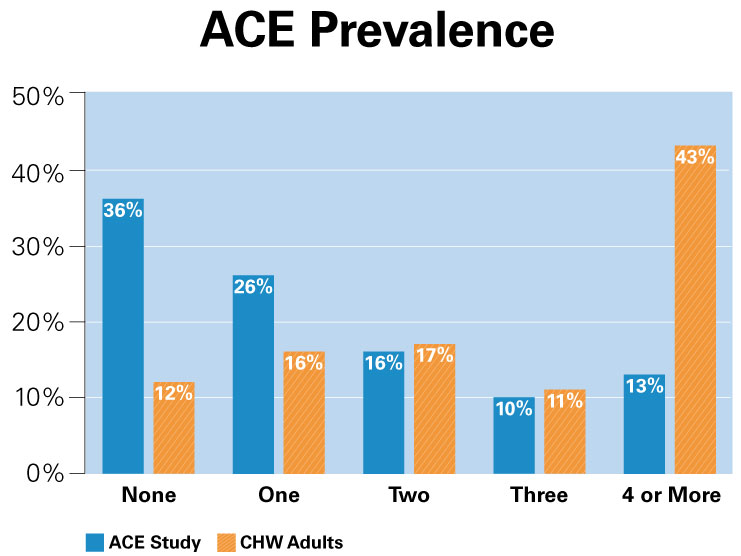

The Well-Being Assessment program is designed so that immediately after children are placed in foster care they are assessed for exposure to adversity and trauma as well as their physical and psychosocial development and functioning. Assessors also gather comprehensive parent/caregiver data, including information about mental health, substance use, intimate partner violence (IPV), economic security, and housing stability. In addition, the Childhood Experiences Survey is used to assess parents’ exposure to ACEs, which can be used to help them acknowledge their own resilience and motivate them to interrupt intergenerational cycles of trauma. The table below illustrates that many adults who are reported to child protective services have ACE histories that place them at risk of many physical health, mental health, and behavioral health problems.

Complementing an assessment of family risk, the program also collects data on protective factors such as family functioning, social and concrete support, nurturing and attachment, and knowledge of parenting/child development.

Compared to respondents in the original ACE study,8 parents assessed by Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin (CHW) Well-Being team are more than three times as likely to report four or more ACEs. High ACE scores have been shown to significantly increase the risk of many health-related problems, including alcohol and drug abuse, depression, obesity, heart disease, and cancer.

Using Evidence to Inform Practice

The Well-being Assessment program fulfills essential functions that facilitate evidence-based practice. The assessment process presents an opportunity to support each family’s active engagement in services. While completing structured assessments over the course of several meetings in the home, Children’s assessors use motivational interviewing techniques9 to build rapport and enhance clients’ intrinsic motivation to participate in services and work toward achieving their goals. Assessment results are reviewed with the family, case manager, and other team members to identify shared goals and service priorities. In addition, initial assessments help to gauge child and family baseline functioning and inform service recommendations. Case management personnel use the data to direct clients to validated interventions at Children’s such as Parent-Child Interaction Therapy and Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy as well as other services and supports in the community that promote safety, permanency, and well-being. The assessment program also gathers baseline data on child and parent/caregiver functioning, which sets the stage for monitoring family progress over time and evaluating service effectiveness.

Pushing the Envelope: The Post-Reunification Pilot Project

The child welfare field currently lacks knowledge related to how families function after a child returns home from foster care. Child welfare agencies rarely gather data to measure child and family progress after reunification occurs. To address this gap, the Institute for Child and Family Well-Being recently launched The Post-Reunification Pilot Project that aims to gather information that can be used to provide families with post-reunification support. Children’s Well-Being Assessment program now continues the assessment process after a child returns home from foster care to track their well-being over time and provide timely support to their family. Ultimately, the collection of post-reunification data is expected to generate information that can support real-time decision making and increase the likelihood that children remain in a safe, stable home environment that promotes their well-being.