The Science

In 2016, School of Freshwater Sciences Professor John Janssen and master’s student Brennen Dow began an extensive mapping project of Milwaukee’s lower estuary, where the city’s rivers and canal meet Lake Michigan south of Bradford Beach. Dow cruised up and down the waterways with a side-scan sonar, a device that collects information about the depth and composition of the waterbed. He used this data to identify likely locations for fish habitats, where he dove with an underwater camera. There he found bluegills, largemouth bass, and northern pike, among other species. Sometimes these fish were in unexpected places: swarming around a discarded motorcycle or taking advantage of cement remnants to hide from predators.

In 2016, School of Freshwater Sciences Professor John Janssen and master’s student Brennen Dow began an extensive mapping project of Milwaukee’s lower estuary, where the city’s rivers and canal meet Lake Michigan south of Bradford Beach. Dow cruised up and down the waterways with a side-scan sonar, a device that collects information about the depth and composition of the waterbed. He used this data to identify likely locations for fish habitats, where he dove with an underwater camera. There he found bluegills, largemouth bass, and northern pike, among other species. Sometimes these fish were in unexpected places: swarming around a discarded motorcycle or taking advantage of cement remnants to hide from predators.

Janssen and Dow designated six “habitat hotspots:” Summerfest Lagoon, the Green Breakwall, South Shore Park, Grand Trunk Wetland, Burnham Canal and a reef in the Milwaukee River near North Avenue. Even though fish were thriving in these isolated areas, their habitats were too far-flung to be fully viable. For example, an adult feeding ground might be too distant from an egg-hatching location for young fish to reach.

For his master’s thesis, Dow compiled a list of all the locations along the 42 miles he mapped with information about depth, composition and wildlife. He suggested projects for each that could help connect and expand isolated hotspots and make the entire estuary a vibrant ecosystem supporting a diversity of fish. Now, as the Milwaukee Estuary AOC Coordinator at the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Dow is putting his proposed projects into action. Meanwhile, Janssen is mapping additional areas and securing grants to support a variety of habitat restoration projects.

Telling the Story

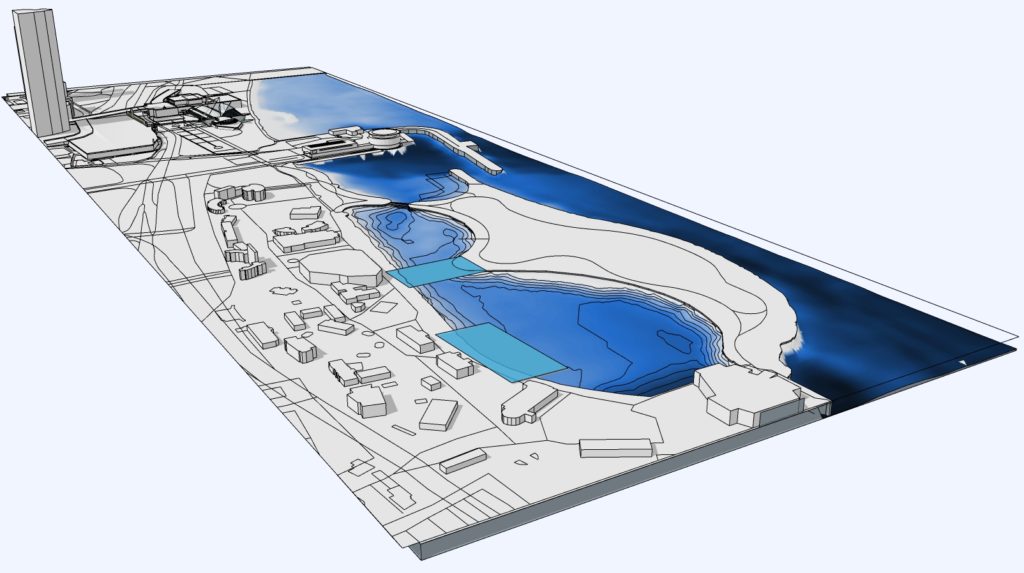

In order to make their findings accessible to the general public, Janssen and Dow collaborated with Peck School of the Arts Associate Professor Kim Beckmann, who designed maps visualizing the harbors complex ecosystem.

Beckmann started with the grainy photos Dow had taken with a side-scan sonar, teaching herself to read their murky shadow and thinking about how to translate that information into a clear visual. Her own curiosity drove her to ask questions that added layers to the estuary’s story about how the fish survive, move with the season and interact with their surroundings. In addition, she presented drafts of the map at public events like Harborfest and Open Doors Milwaukee and asked visitors what they would like to see represented.

At that point, it was clear to Beckmann she would need to make multiple maps to accommodate all the information. She created one 36- by 44-inch map showing the entire lower estuary with the biological hotspots highlighted in orange and four 24- by 36-inch maps zooming in on various locations. In addition to showing where the fish live, they feature colorful paintings of the various species, schematics visualizing how fish populations fluctuate with the seasons, and information on diet and migration, as well as opportunities for recreation.

Beckmann’s design philosophy is rooted in accessibility; she chose a color scheme that is readable to people with colorblindness. She crafted the maps to be rich with information, inviting people to spend time exploring, but also distilled the information enough to make it clear to a nonscientist. In addition to being available here, the maps will be printed and sent to stakeholders and area schools. Some groups are already using them to guide their conservation projects, and Beckmann is onboard to design maps of Port Washington, Sheboygan, Two Rivers, and Manitowoc as the project expands.

Producing Results

The maps you see here are guiding the clean-up and restoration efforts currently underway in the Milwaukee Harbor. Multiple state agencies and nonprofits are using the information to make strategic decisions about what projects they will undertake.

The efforts to clean up the Milwaukee estuary began in earnest after 1987, when the Environmental Protection Agency declared it an “area of concern,” meaning that hazardous waste has significantly impaired the area’s natural resources and made outdoor recreational activities like fishing difficult, if not impossible, to do.

The efforts to clean up the Milwaukee estuary began in earnest after 1987, when the Environmental Protection Agency declared it an “area of concern,” meaning that hazardous waste has significantly impaired the area’s natural resources and made outdoor recreational activities like fishing difficult, if not impossible, to do.

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Area of Concern Team, along with other stakeholders like the Harbor District, Inc., are working to get the harbor off the area of concern list. To support those efforts, Janssen and Dow not only mapped the harbor but also compiled a list of suggested projects at each location. Dow is now working at the WiDNR, leading the effort to put that research into practice and scale it to address the entire Milwaukee area. Many of these suggested projects seek to expand and connect the habitats that Dow identified.

The mapping project also led to the creation of the Western Lake Michigan Harbors group, a consortium including UWM, the Army Corps of Engineers, Harbor District, WiDNR, Fund for Lake Michigan, Port of Milwaukee and others. In addition to submitting a number of grants, it secured a commitment from Army Corp of Engineers to expand the Green Breakwall, a wave and weather barrier in the harbor with habitat features near the North Gap Harbor entry.

Janssen has received grants from Fund for Lake Michigan to expand habitat for bass and pan fish spawning in the Summerfest Lagoon and map four other Lake Michigan Harbors: Port Washington, Sheboygan, Two Rivers and Manitowoc.

Finally, Dow and Janssen’s findings are supporting restoration projects along the proposed Milwaukee Harborwalk, in the Burnham Canal, and at Grand Trunk Wetland.

We would like to acknowledge and thank all those who’ve contributed to this work including members of the Janssen Lab past and present and especially the contributions of Jeff Cable, Jim Edlhuber, and Virgil Beck.