As a high-school history teacher, Terrance Newell didn’t need to read a research study to realize video games and simulations shaped the way his students learned.

Teens who struggled in his class worked their way through elaborate video games at home: gathering information, navigating complex scenarios, learning through trial and error.

“Millennials are used to problem-solving, multitasking and learning new skills informally using video games,” says Newell, who is now an assistant professor of information studies at UWM. “A video game is a problem matrix.”

Although research shows students can learn from videogames, most retail or off-the-shelf games aren’t suitable for the classroom, Newell says. While the commercial games may have snazzy graphics, many popular ones focus on first-person shooting scenarios, or using map skills as a way of tracking enemies.

“Students learn things, but potentially the wrong things,” says Newell. “The content is not suitable or tailored for educational purposes.”

Playing to learn

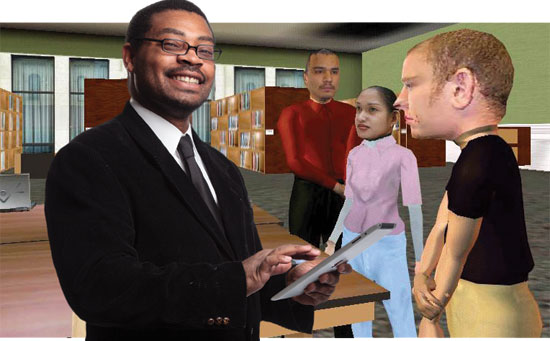

Newell’s information-literacy simulation creates a virtual school library where students can interact with “cybrarians” as they learn how to search out and evaluate information.

So Newell set out to design his own educational games and test them to see what impact they had on student learning. In one of his initial research projects, he created an interactive simulation on “information literacy” – designed to help students learn how to locate, evaluate and select information, using both 21st century technology and traditional resources.

Newell’s simulation game, “21st Century Learning Labs,” tested with middle-school students, featured an interactive, computer-generated community with schools, libraries, and other, informal information sources like museums. Student players sought out information on virtual computers and in virtual books and encyclopedias, guided by virtual “cybrarians.”

Students could also become information-literacy apprentices, and progress from novice to master in information problem-solving. Newell worked with classroom instructors in creating the simulated middle-school world, complete with hallways and lockers.

Over a four-week period, Newell compared two groups of seventh- and eighth-grade students in a computer-literacy class, which was located next to the library.

Students were assigned to research complex problems that required multiple sources of information. They had to search websites, watch and listen to online videos, and search catalogs to do the required problem-solving. This information problem-solving involved a number of tasks – locating resources, accessing information, interpreting and communicating information, and evaluating the results and the process used.

One group was led by teachers who worked with the students face-to-face, but did not use the simulation. The other group, though guided by teachers, used Newell’s simulation to solve the information problems. The simulation allowed students to use their keyboard, mouse and computer screen to move about using avatars, and communicate via chat features and gestures.

The results, published in School Library Media Research, showed that, overall, students who used the computer simulation improved more in information problem-solving. However, students who worked with teachers face-to-face understood the content they learned better, while those who used the computer simulation understood the processes better.

The results on learning content via the simulation may have been impacted by teacher concerns about if and how much they should work with the students and “cybrarians” in the simulation, says Newell.

Supplement, not substitute

Research starting in 2012 will look at how students working in teams can learn using games and simulations on an iPad. The models in this photograph are not part of the research.

As a former history teacher, married to an assistant professor of education, Newell certainly isn’t looking to replace teachers or librarians with virtual counterparts. “Nothing can replace face-to-face teaching. These simulations are not designed to substitute for the teacher or the librarian. We see them using the simulation to supplement the learning process.”

As a researcher, he’s looking to find and test the best ways to combine games and simulations with face-to-face teaching in K-12 education. That’s one of the reasons he moved from education to information studies.

Currently, he’s doing additional testing on the effectiveness of the information-literacy simulation, and designing other simulations for content areas like history, science and mathematics. In a research project starting with an elementary school in 2012, he’ll have 16 iPads available that students can work with in teams of two. That will give him the opportunity to collect information on collaborative learning within simulated contexts.

“My ultimate goal is to develop and test a suite of simulations that teachers and librarians can use.”

Eventually, he’d also like to explore an interesting finding that wasn’t part of his formal research – the impact of the simulation on classroom behavior.

“In one classroom, I observed some out-of-control behavior and disrespect for teachers before the study. After they implemented the simulation, it was like day and night. Students were engaged and focused, and helping each other problem-solve.”

With a full-time career and a 3-year-old daughter, Newell says he doesn’t have the time or inclination to play a lot of video games himself.

“I enjoy designing the games and creating the backgrounds, but I’ve always been more interested in the education aspects. I like to think about ways to get students motivated and excited about educational content.”