The secret lives of birds

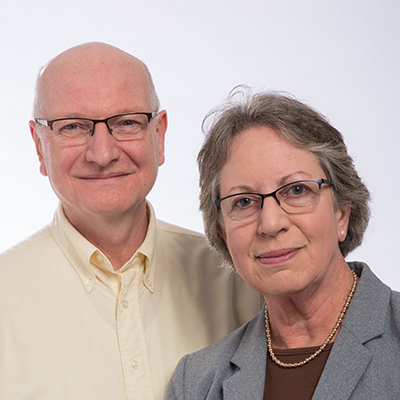

For a research lab, this one has quite the view. Ornithologists Peter Dunn and Linda Whittingham are in their 21st year of studying tree swallows here at the UWM Field Station, set within a 320-acre wetland near Saukville, Wisconsin.

“It’s undisturbed,” says Dunn, a distinguished professor of biological sciences, “so you can record long-term change.”

It’s allowed Whittingham, a professor of biological sciences, and Dunn to uncover a secret life among female swallows: They quietly have extra mates, while the jilted male tends the nest containing offspring that he may – or may not – have sired.

Ninety percent of birds are monogamous, with mated couples raising their young together. But Dunn and Whittingham are most interested in birds that don’t follow that playbook because such behavior could lead to better disease resistance in their offspring.

For some birds, the strategy of “fooling around” increases the number of healthy offspring while passing along genes tied to strong immune systems – and better survival. Dunn and Whittingham have shown that females seeking extra mates are attracted by male plumage that tends to be brighter. They also found that extra-pair matings produce offspring with brighter feathers, suggesting a reproductive payoff for both males and females.

This avian preference for the beautiful is more than feather-deep, Dunn says. If certain physical traits are signals of genes for strong immune systems in birds, could a similar benefit exist in humans, who also use immune systems to fend off disease? “We’re not that far away in basic animal research from things important to humans,” he says.