Raising children is tough enough, but can be especially challenging for young parents who may not have expected to add a baby to their lives.

The Young Parenthood Program, based in the Joseph J. Zilber School of Public Health, is focused on helping teens and young adults learn to work together to raise a child – even if they don’t choose to remain a couple.

“There really isn’t another program that works with young couples to help them with co-parenting,” says Paul Florsheim, associate professor in the Zilber School of Public Health, who developed the program.

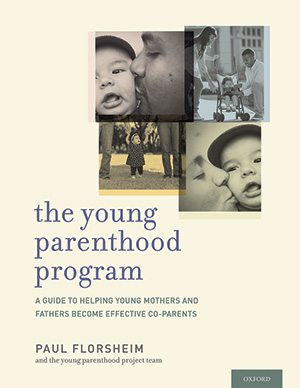

He started the work at the University of Utah, and continued it under a grant from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services’ Office of Adolescent Pregnancy Programs. His book on the topic, “The Young Parenthood Program: A Guide to Helping Young Mothers and Fathers Become Effective Co-Parents,” was published this spring by Oxford University Press.

The issue is vital. Four out of ten babies in the U.S. are born to unwed parents, according to U.S. Census data, the highest percentages to minority, economically disadvantaged parents under the age of 25. The very idea of “family” has dramatically changed over the past few decades, according to Florsheim.

Building strong networks, communication skills

Research shows that children who are born to young mothers, and grow up without fathers in their lives, are at higher risk for academic and behavioral problems. Getting the fathers involved before the baby is born and helping the young parents learn to manage stress and communicate better may help ease some of these problems, says Florsheim.

Young parents are at risk for engaging in dysfunctional parenting practices and intimate partner violence, and face additional challenges on top of their own developmental struggles, according to Florsheim.

Clinical trials have indicated that couples who participated in the Young Parenthood Program demonstrated better relationship skills, lower rates of intimate partner violence, less paternal disengagement, and more positive parenting behavior among young fathers.

Social workers and other mental health service providers can help young people adapt to becoming parents, he adds. However, many professionals lack formalized training in this area and there are few programs available to give the necessary support to young parents, says Florsheim.

When grant money was cut halfway through the original research project due to federal budget cuts, Florsheim was determined to find a way to make the program work on a shoestring budget. Two Zilber School doctoral students, Jill Denson and Mary Mazul, helped Florsheim create a partnership with Milwaukee Health Services Incorporated and St. Joseph’s Hospital, then apply for a grant. Now the Lifecourse Initiative for Healthy Families has provided funds to adapt the program so that it can be offered through prenatal clinics. The team will soon launch a new study designed to test a more efficient version of the co-parenting support program.

Partnering with prenatal clinics was a good fit for the program, Florsheim says.

“This is the type of community-based research that I hoped to do when I came to UWM to help start the Zilber School of Public Health.”

In other recent public health news, city officials are seeing troubling increases in the rate at which babies continue to die in Milwaukee before their first birthday. Especially troubling is the rate at which African American babies die. “Black infants are still about three times more likely than white infants to die in Milwaukee,” says a June 3 article in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

Among the areas that need to be addressed to lower infant mortality rates are reducing “lifecourse stressors” that impact prematurity — from safe neighborhoods and fatherhood involvement to early childhood education and job preparation programs.