Virtually Limitless

UWM's Immersive Media Lab stretches the boundaries of virtual reality.

Chris Willey hands me a pair of bulky rectangular goggles, shows me how to fit them over my head and tells me to close my eyes. A screen inside the goggles blinks on, casting a white flash against my eyelids. It dims, and Willey tells me to take a look.

The impact is immediate. I know for a fact that I am in a concrete-floored office loft inside the Kenilworth Square East building of UWM’s Peck School of the Arts. But it seems like I’m drifting thousands of miles away. I can feel the curve of the chair along my back and the hard corner of the table pressing into my forearms, and yet, I am drifting in space somewhere behind the dark side of the moon.

It’s my first experience in virtual reality, and it’s breathtaking how quickly my brain accepts the premise. Willey introduces some VR terminology for this experience, saying my “mindbody” is in space, a way to distinguish the virtual sensation from physical reality. I hover far above Earth as it spins in a crazy orbit below me. Countless stars dot my 360-degree view. Well, 8,884 stars, actually, since those are the data points Willey and his collaborators used to code this particular simulation, a joint effort between astronomy professors, art teachers and enthusiastic undergraduate researchers.

“This is coming from nothing but code,” Willey’s voice says somewhere off in space to my left. “We have literally conjured up everything that your brain is currently experiencing from scratch.”

A Change in Perspective

While my mindbody hovers in space, my real body is conducting an interview with the creative director of the Immersive Media Lab. Founded in February 2017, the lab is home to UWM faculty, lecturers and students who, armed with little more than a DIY ethic and belief in collaboration across disciplines, are grappling with what’s possible in virtual reality. The experiences they’re creating aren’t just sensational, but educational. Their vision: people from backgrounds in science and humanities joining forces to teach complex topics in accessible ways.

Virtual or augmented reality devices are “disruptive technologies,” says Willey, a Peck School lecturer in digital studio practice. Like smartphones or autonomous cars, they’re an advance in technology primed to become a ubiquitous part of our everyday life. It might take a decade, he says, but “this is going to disrupt the traditional college model. This is a tool, and I literally can’t think of a research area on campus that couldn’t benefit from it.”

The Dark Side of the Moon demo was a first modest step toward what Willey calls a “proof of concept,” and it started, of all places, at a party.

Willey’s partner, Tonia Klein, works in UWM’s physics department, and she introduced him to some of her colleagues, who asked what he was working on. He launched into the wonders of virtual reality and remembers saying something like, “Wouldn’t it be cool if we made a pocket planetarium?”

“It turns out,” Willey says, “that I said it to someone who you can’t say that kind of stuff to without it happening. I didn’t know this at the time, but David Kaplan is a hummingbird of productivity.”

Kaplan, along with Dawn Erb, both associate professors of physics, met with Willey and his students. They brainstormed where educational needs and gaps in their teaching matched what VR could do. The first project involved placing several thousand stars into a virtual sky, mirroring how they were mapped during a European Space Agency survey.

“When we opened that file the next time we got together,” Willey remembers, “it was the universe.” It was the first time he realized how raw data, rather than creative imaginings, could be turned into a VR experience.

They debuted the VR project at a local DIY festival called Maker Faire Milwaukee. Watching adults and children alike gaze in wonder into their goggles, Willey says, made them realize that VR could be a powerful teaching tool.

VR can go beyond helping your brain learn new information. It can change your soul.

“When we teach astronomy,” Kaplan says, “we wave our hands a lot and show some static videos or basic 2-D animations. The ability to have interactive and immersive 3-D environments could be a huge leap forward in how we do this, especially if we can get the VR technology working on a scale that is accessible to hundreds of students.”

After that initial universe experience, Willey and his students created the Dark Side of the Moon VR simulation. And, really, they’re just getting started.

The Immersive Media Lab is working on a more interactive simulation, this one geared toward explaining the physics behind the phases of the moon, which Willey’s astronomy collaborators say is deceptively tricky to teach. It’s one thing to read about something in a book or watch a video of where the sun is in relation to the moon and the Earth. It’s altogether different to head out into space and, using virtual gloves known as haptics, reach out and move the moon around. “When you’re controlling the clockwork orbits,” Willey says, “you’re going to understand the mechanics so much better.”

This concept also holds true for decidedly smaller topics. For UWM student Natalie Krug, virtual reality is a way to explore, well, inner space.

Krug, an art education major, came to Milwaukee with designs on a career as an illustrator but ran across virtual reality at an exhibit of undergraduate research projects. Some students had mapped the surface of an iris and all of the intertwined muscle fibers that open and close the pupil. “You put on these virtual reality goggles,” Krug remembers, “and could weave in and out of the structures.”

Medical illustration and art in general suddenly took on new possibilities. Krug immediately asked Willey if she could join the lab, and she’s now working on a virtual model of the entire human eyeball. It’s like the “planetarium experience” for biology, she says, where people can put on a pair of VR goggles and gloves, and “interact with it and see and poke and tug.” She thinks such immersive educational experiences will be part of the future of her profession.

But it isn’t only VR’s potential as a science education tool that excites Krug. Like most Immersive Media Lab members, she thinks that when you strap those goggles on, VR can go beyond helping your brain learn new information. It can change your soul.

Lessons in empathy

The true power of VR, says Immersive Media Lab member Emily Berens, is not how it puts you somewhere else, but how it puts you in the shoes of someone else.

“A lot of my research is around making VR a community experience, specifically with a focus on empathy,” says Berens, a Peck School associate lecturer in digital studio practice. It’s an idea she first encountered in the “immersive journalism” of documentary filmmaker Nonny de la Peña.

De la Peña created Hunger in Los Angeles, the first VR video to premiere at the Sundance Film Festival in 2012. Viewers donned VR goggles to experience a simulated food bank and would often pull off the VR goggles in tears. The power of VR, de la Peña said, is its ability to let a viewer experience a story emotionally and then “take that back into their lives.”

For Berens, this idea has resonated as she explores new ways of connecting students to the bigger world around them. She’s part of the Milwaukee Visionaries Project, an after-school art and film program for Milwaukee Public Schools students. She’s working toward including VR experiences into the Visionaries curriculum.

Berens also works as an advisor and mentor for UWM students interested in immersive media research. For instance, she’s working with Krug on implementing VR into her art education studies.

Berens knows many teachers are using Google Classrooms in their curriculum. “Kids who wouldn’t necessarily be able to go on field trips can now take field trips across the world,” she says, and she wonders at the next-level possibilities. How much more powerful would those computer-assisted field trips be if they occurred in virtual reality? Would it help them better understand the social issues shaping our world?

Yes, according to some fledgling VR research at Stanford’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab. Experiments have shown that experiencing VR simulations of humanitarian or environmental issues makes people more likely to feel stronger connections to that cause and more likely to donate money or take action.

For Immersive Media Lab members, these are important results. VR could easily become a technology for nothing more than entertainment, a doorway to the future depicted in the novel and movie “Ready Player One.” There, people binge on virtual video games, spending more time in a fabricated world than the real one.

But that would be a waste of the technology’s potential, which is why the lab’s faculty, staff and students are exploring its higher possibilities.

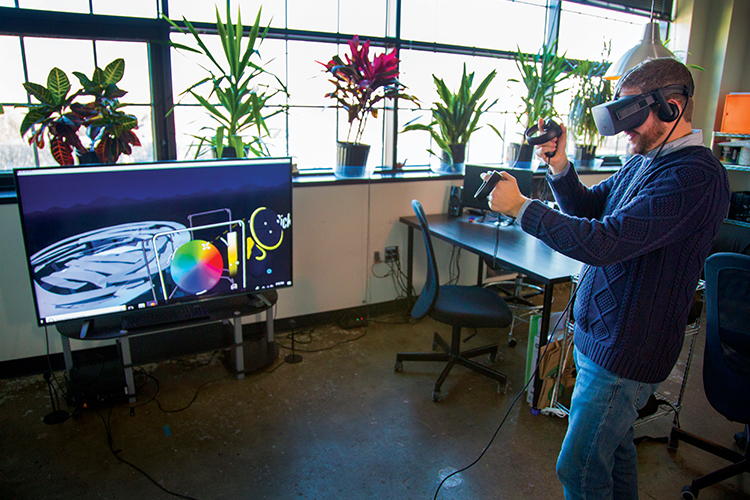

“I’m seeing an evolution that’s going on in education and technology and culture,” Willey tells me, “and my goal is to provide the space that allows for these ideas to come together.” He’s now plugged into the lab’s virtual reality system, creating a painting by waving his haptic-gloved hands around, making broad virtual brush strokes. Behind him, a large, curved high-definition monitor displays the three-dimensional landscape those strokes have created.

Willey trained as an artist in a two-dimensional world, complete with rules and vanishing points and perspectives. Now, though, his mindbody is in a virtual space where he’s surrounded by every brushstroke he’s made, the painting stretching away from him on all sides.

He feels a bit unmoored, he says. Because the technology is so new, very few user manuals exist to teach people how to make virtual reality spaces. There are even fewer about how to use it as a teaching tool.

He and his colleagues in the Immersive Media Lab are, quite literally, conjuring up our future.