The language of learning

Preparing teachers to work better with bilingual students

Tatiana Joseph vividly remembers her first day of school in the United States at age 10. She and her family had moved from Costa Rica to Milwaukee, and she was suddenly plunged into a new school system where everything was in a different language. She knew only three words in English, emergency ones that her father had taught her: lost, help and bathroom.

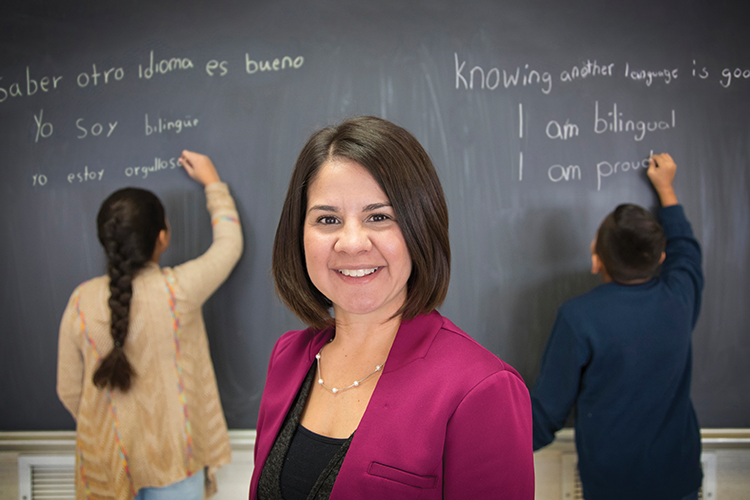

“Every time I walk into a classroom now where there are English-language learners, I remember that first day and thinking, ‘What am I going to do? How am I going to survive this?’” says Joseph, now an assistant professor of teaching and learning in the School of Education. She knows she was fortunate to have a bilingual fifth-grade teacher who made her feel welcome and helped with academics, because her education was conducted mostly in English.

All of this played a role in Joseph’s career – she’s now chair of UWM’s second language education program – as well as her research interests. “I think it’s those life experiences,” she says, “that have really helped me adopt a different lens on what I want to do in teacher education, and how I want to rethink the way we work with English language learners.”

Some school systems have a student population in which more than 20 percent of the children speak a home language other than English. Teachers may find themselves working with children who speak Spanish at home, or perhaps Rohingya, Swahili, Arabic, Laotian or any number of other languages. These are the reasons that Joseph, a former teacher and member of the Milwaukee Board of School Directors, believes that teachers must be properly prepared to work in linguistically diverse classrooms.

Research that Joseph and others have done shows that teachers can build on their students’ first language to help improve their overall educational progress. That includes building proficiency in the English language. “In order for children to learn English,” Joseph says, “they have to have a strong foundation in their primary language.”

Backed by that research, educators are shifting their focus from treating a student’s non-English home language as a deficit and instead appreciating it as an asset. The change in approach is reflected in new terminology like “biliteracy” and “dual-language learners.” It’s also prompted some innovative programs that have shown positive educational results, such as sending young children home with books printed in their home language to be read with their parents.

To be clear, educators agree that children need to learn English. “There is no thought that we should neglect that,” Joseph says, “but the argument is that we teach it from an approach where we are respectful of who the student is and what they bring to the table.”

With that in mind, Joseph and School of Education colleague Leanne Evans authored a 2018 article in the Bilingual Research Journal that addressed preparing teachers to do more than teach language skills. In it, they highlighted the need to prepare teachers to uphold children’s cultures and languages as cornerstones of building anti-racist and anti-biased classrooms and communities.

Joseph notes how English as a second language education was once seen as an entirely separate endeavor within schools. Now, the trend has moved away from sending children to separate classrooms and toward helping classroom teachers work with all children, while also supporting students with extra help when needed.

That doesn’t mean teachers need to be fluent in another language to work with English language learners. The key, Joseph says, is offering these students a welcoming environment, and showing respect for the home language and culture. “You can bring books, you can bring experts, you can bring in families,” Joseph says.

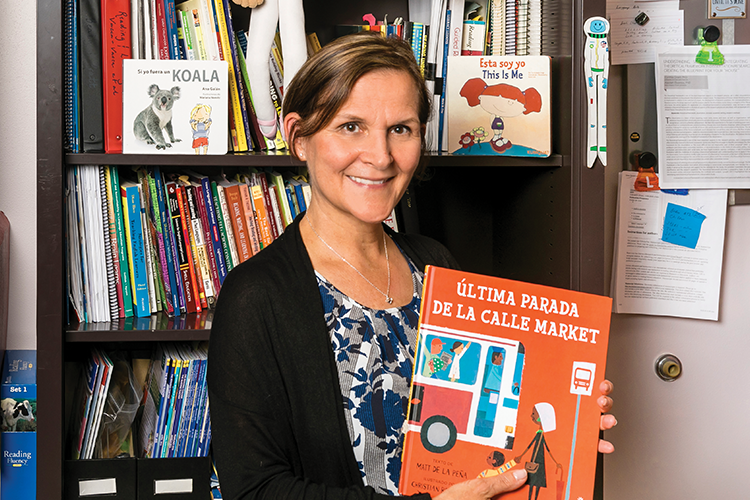

Evans, an associate professor of teaching and learning who focuses on early childhood education, explains how children can build literacy across languages, even at a very young age. Just learning how books in print work, for example, builds a foundation.

“If children know how to track words left to right in Spanish, when it comes time to read an English book, they already have that knowledge. They don’t need to relearn that,” Evans says. “What they need is just to have that vocabulary in a second language. It’s called language transfer.”

Evans points to some promising research that resulted from her work with children in Head Start centers that serve a primarily Latinx population. The Leyendo Juntos project – Spanish for “Reading Together” – involved schools providing books in Spanish or Spanish/English that children would take home and read with their parents.

Families would get a note with suggestions on ways the books could be used and how to talk about the books together. Children might, for example, draw their favorite part of the book, sometimes with parents transcribing what the child said.

“We teach children to think and talk about their languages,” Evans says, “and make it OK to wonder about how it’s done in one language versus how it’s done in another language.”

Evans began the project by working with 4-year-olds in both center-based and home-based programs that served more than 400 families. Later, she and undergraduate student Alexandra Campos expanded it to include about 60 children up to age 3 in similar programs.

Leyendo Juntos proved helpful to the children and their families. Researchers learned that discussions between parent and child, as well as teacher and child, were critical. The project also allowed teachers and parents to partner toward a better understanding of the nuances of bilingualism and biliteracy.

“We wanted to create school-to-home and home-to-school partnerships around the children’s literacy in both languages,” Evans says. “We wanted the parents to know when you work with the children in the language they first learned to speak, those skills will transfer over.”

Their research continues to examine how early childhood teachers are designing and implementing home literacy programs, as well as what support they need and the challenges they face. It is one of many important building blocks that help construct a child’s educational foundation. But the value of encouraging bilingual or multilingual classrooms goes beyond learning languages.

“By teaching or learning another language and culture, and all the components that come with that, we are teaching empathy,” Joseph says. “As language teachers, we have that power to re-create and re-establish what mainstream society could look like.”