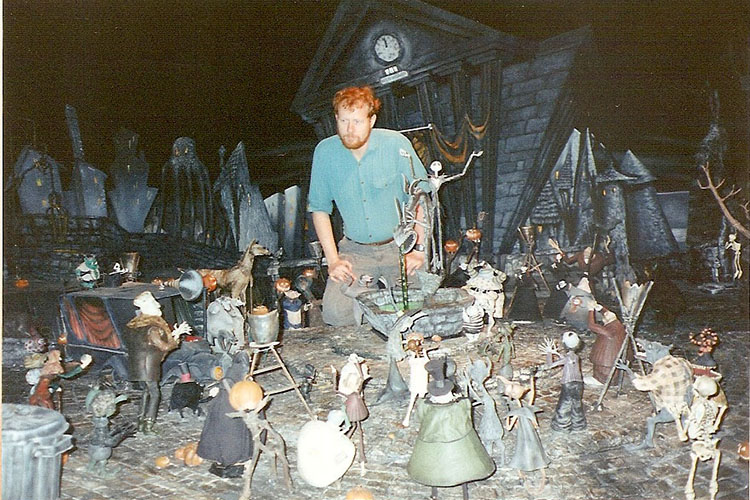

More than 25 years after its release, “The Nightmare Before Christmas” is increasingly regarded as a Halloween classic. What local fans might not know is that “Nightmare” has a strong UWM connection. Film, Video, Animation, & New Genres lecturer Owen Klatte is a stop-motion animator who worked on the film’s production team.

He’s excited to be in the audience on Sunday, Oct. 20, when the film screens at the Riverside Theater, accompanied by the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra playing Danny Elfman’s celebrated score. Klatte, who fell into stop-motion because he loves art but says he can’t draw, attended the event last year and says he could not believe how spot-on the live performance was, with the MSO right on the beat scene for spooky scene.

Klatte recently shared his favorite experiences from his time on the “Nightmare” set and talked about nurturing a new generation of animation talent in the Peck School of the Arts Bachelor of Arts degree in animation.

How did you get connected to “The Nightmare Before Christmas”?

I got a late start in stop-motion animation, but my big break was working on “Gumby.” It was through “Gumby” and a couple connections that I ended up meeting (“Nightmare” director) Henry Selick. Henry had worked with Tim Burton at Disney in the early ‘80s, and by that time we had a core group of people who knew how to do stop-motion animation pretty well. He called a bunch of us into his studio – there were seven of us original animators – and I can still remember seeing Tim Burton’s drawings for Jack, Sally, Mayor and Oogie Boogie. We were all blown away. I’d never seen any designs like that, before or since, that grabbed me the way those did. Sometime after that we started working on it. It was just a really lucky series of breaks, being in the right place at the right time.

How long did the entire process take?

Seventeen months, I think. It takes 24 frames to make one second of film, and the average animator would create about five seconds of finished animation a week, and that’s a 50- or 60-hour week. The scene where Jack is on the stage handing out Christmas assignments to people and he’s digging through a box, and Sally is standing behind him telling him she had a vision, that shot is about fifteen seconds long and I spent about 100 hours on it. Stop motion is a slow process.

Do you have a favorite scene?

Well, I think the single best shot in the movie was done by Trey Thomas. It’s the shot where they’re making Christmas, and you’ve got the harlequin demon taking this rat and pounding it, and Jack is behind him saying, “oh something fresher.” It’s a beautifully animated shot. Perfect shot. The best shot I probably ever did, or the shot that came the closest to what I wanted it to be, was a simple shot of the Mayor, just before Lock, Shock and Barrel come onto the stage and the Mayor is sitting up on his desk and he takes his megaphone, looks at it and pounds on it. Then he reaches in and grabs the spider and puts it on his collar. That was so right on, it was off by one frame. If he had hit the spider one frame faster, it would’ve been perfect. But that’s the kind of attention to detail you have to get, and it was off by one twenty-fourth of a second!

Tell me about the animation program at UWM, which was recently launched.

I teach stop-motion animation and a class about the business of animation, what it takes to get into it, how to get into it, what that’s like. We have Tim Decker; he was a “Simpsons” animator, and he teaches character design and puppetry, storyboarding, various writing and animation. We have a couple different people who just teach the basics of animation. It’s an interesting balance of the fine art end of stuff and experimental animation, and then the business end of professional and commercial animation. We try to expose students in the program to both.

What is your vision for the program?

I personally like to focus on the fundamentals of animation and getting students to really understand the principles. That’s the kind of thing that carries over into whatever kind of animation they would do later – computer graphics, stop motion, or something else – so that they’re well rounded and can work in any field with a little training on whatever the particular tools are. There’s also a focus on creativity because the thing that will make people successful in animation is higher-level thinking. Being able to be creative and original, coming up with designs and pooling ideas that will engage and entertain people. It’s not just about the nuts and bolts; it’s about thinking right.

Are there any fun facts you’d like to share?

Everything in this movie virtually was done on a camera. It could’ve been made by computer graphics at that point, but we didn’t do that. In Oogie Boogie’s song when the three slot machine guys come out, and they fire their guns at Santa as he’s being pulled away, the muzzle flashes on those guns were done with a rusty nail. I would animate the characters – Oogie, Santa and the slot machine guys – and I covered my hands in black cloth, held a Dremel tool and a rusty nail, and I’d hold the nail right by the end of the gun and hit it with the Dremel tool to spark the nail. We’d shoot that, and the moment the slot machine guy was going to shoot his gun, we would double expose the shot with the sparks from the rusty nail. It was this real old style of funky tricks. If you look at it carefully, the flash and the gun are misaligned at times.