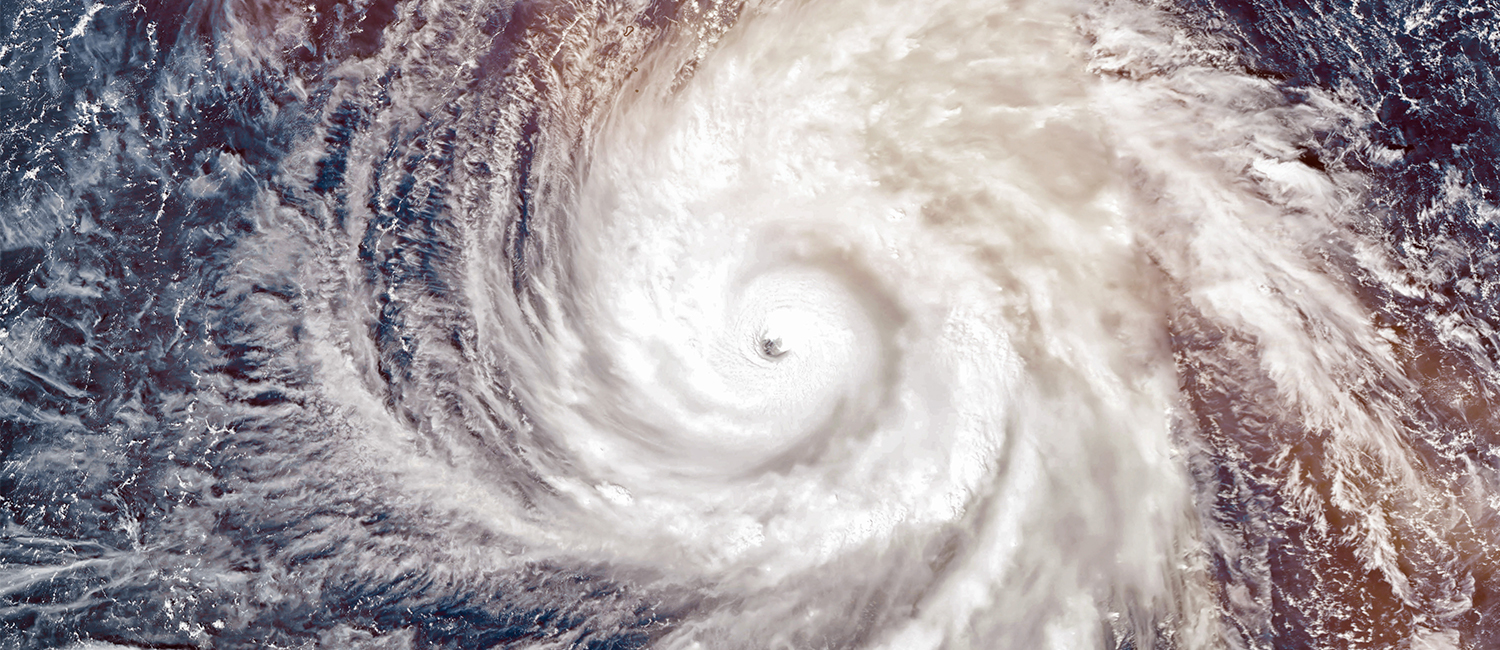

Learning why some hurricanes are more dangerous inland

In almost every region where hurricanes form, their maximum sustained winds are getting stronger, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. And NOAA predicts it’s likely that greenhouse warming will cause the most intense hurricanes to be even more intense in the coming century.

Most of these storms strengthen when over water, then weaken after making landfall. But research by Clark Evans, an atmospheric science associate professor in the College of Letters & Science, explores how some tropical storms, including hurricanes, threaten inland areas by maintaining, or even intensifying, their power once they’ve moved inland from the coast.

Evans hopes the research leads to a better understanding of the core physical and thermodynamic processes that support such storms maintaining their intensity or increasing it while over land. He also wants insight into another important aspect: “How well can we actually predict this?”

Evans grew up in Orlando, Florida, and encountered his first hurricane – Erin – in 1995. His ongoing research uses models to examine two theories on why some tropical storms don’t lose intensity over land. One is that they draw energy from the wet ground directly below them. The other is that the energy comes from the warm, moist oceans hundreds of miles away and is carried by warm winds toward the storm.

The research uses factor separation, in which individual physical processes – such as exchanges of heat and moisture between the ground and air – are isolated in simplified weather simulations. Doing this helps identify which processes are most important to tropical storms that don’t weaken over land.

“It also considers collections of weather model simulations, starting with marginally different atmospheric conditions,” Evans says. “They help determine the importance of these physical processes relative to our inability to perfectly forecast the weather.”